What an odd story. As we know from our history as well as right up to today, brewers usually go in the direction from rags to riches – starting out in sheds and garages to become multimillionaires all the while pretending they are still small operators working on the level of a craft industry. Oh, how we laugh when that old fib is rolled out, don’t we? Well, it didn’t work out that way for Har(r)ison and Leadbetter, a brewing concern which operated apparently briefly but seemingly quite splendidly in New York City in the last half of the 1760s. It was located on that wee point sticking out in the Hudson River. Click on the image for a bigger version. As you will see, there is a bit of biography involved as well as a bit of mapping if I am to explain this so bear with me.

Let’s start with the man who was born into this world as George Harison but died as George Harrison – adding another “r” to the family name. This guy was exactly the sort of guy the Revolution was all about. Fortunately, he ended up at one point as the Grand Master of the Masons of the Province of New York, as a story in the New York Journal on 24 October 1771 shows – which means there is a reasonable amount written about him and his by, you know, my brothers… if my brothers would, you know, have me… being as lapsed a Mason as one can be. George (b.1719, d.1773) was born to Francis and father to Richard. His father and his son were great political leaders of their day. Francis was an Oxford trained lawyer who comes to New York in 1708 and, in 1720, was made a member of the New York Governor’s Council; in 1721, becomes Judge of the Court of Vice-Admiralty in New York and, in 1724 is Recorder or Clerk of the City of New York. He returns to England in 1735 and dies in 1740. Big time Loyalist power holder and lackey. Two generations later his grandson Richard (b.1747. d. 1829) is a New York born, Oxford trained lawyer who, after the Revolution ends in 1783 is a New York state legislator, a member of constitutional convention, the first US federal attorney under Washington at New York – and also Recorder or Clerk of New York City. Like grandpa, big wig.¹

Sandwiched between Francis and Richard? George.* What can we say about George? It is clear he is very rich. His father dies in 1740 when George is just twenty-one. That same year, George sells off a 1400 acre farm “six miles above of Newborgh” or what is now Newburgh. Later that decade, he sells off more than ten times that much land. In the New York Gazette of 25 April 1748 a notice is placed for the gathering of creditors who owe money to the estate, to meet George as heir and also to sell 15,000 acres of land which have been divided into 100 and 200 acre lots. In 1750, he buys 2,000 acres of Ulster County, NY. Suffice it to say, George as heir is loaded.

What then of Leadbetter? No so much about Leadbetter because he is not a big wig and might not even have been a wig at all. From 1764-65, he appears to be in a brewery partnership at Brooklyn Ferry with Thomas Horsfield brewing English ale, table and ship beer. The Horsfield’s Long Island Brewery was created in the early 1750s and continued into at least the 1780s… but that is for another post.

Enough about these people. What about the brewery? The partnership is described in the Masonic history of the George this way: “In 1765 he went into the brewing business with his father-in-law and James Leadbetter, a professional brewer.” Hmm… father-in-law. In the 12 May 1766 edition of the New York Mercury, to the upper left, a notice of the opening of the new brewery is announced, stating that only ship and spruce beer were to be had as yet but that ale was coming. To the upper right is the one from 7 July 1766 from the same paper stating that their ale was for sale. Notice that Harrison is located on Broadway. The next April, we see he has moved. The New York Gazette announced on 9 April 1767, as we see in the lower left above, that George moves from Broadway to the brewery lands. Ale, ship and spruce beer are sold and – interestingly – folk are told to be mindful about returning their empty casks. Was this a sign of problems? Whatever it was, things do not last. As we see in the 12 October 1769 edition of the New York Journal to the lower right, James Leadbetter announces that he is leaving for England and is selling his three-eighths interest in the brewery. The notice has a wonderfully detailed description of the site. There is a brew house of 60 by 30 feet with both a 15 and a 50 barrel copper. There is a mill house for grinding malt and pumping water that is 30 by 25 feet. The malt house of 60 by 31 feet is four stories high with two kilns and two lead cisterns for steeping barley. The store house is 70 by 23 feet and comes with an underground vault. There are stables and a cooperage and four dwelling houses along with land including 18 fenced acres. A significant industrial scale brewing operation. And the brewer is leaving.

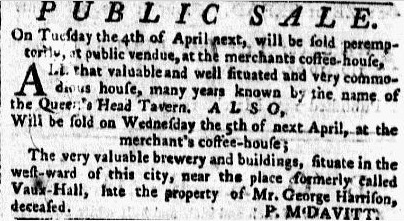

What happens next? James Leadbetter appears to become a man of leisure and a bit of the lord of land himself – and he doesn’t leave for England. In 1770, Leadbetter becomes on the the original grantees of the Wallace Land Patent, a group of land speculators getting their hands on 28,000 acres along the Susquehanna, a strip two miles wide. In the New York Gazette of 26 November 1770 he is offering organ and harpsichord lessons to gentlemen and ladies. In the early part of the Revolution, Governor Tryon enlists Leadbetter to spy on the Revolutionaries. A James Leadbetter – late of New York with lands in America – has his will proven in 1799 in England** leaving a son in London and a daughter in New York.

The brewery and the Harisons went on, still playing with adding the

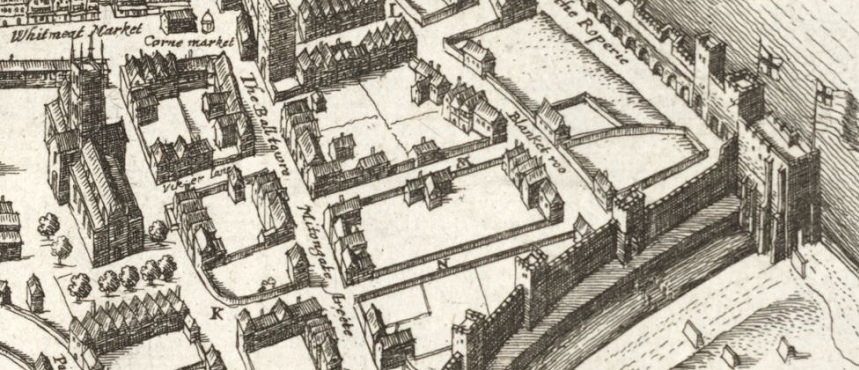

second “r” as they do. Though one for a bit more time than the other. Upper left is the obituary for George in the New York Gazette of 26 April 1773. He was only 54 when he died. Before he left us, he seems to have sold the debts of the partnership to a shopkeeper, David Jones of Broadway, who according to this notice in the New York Gazette of 10 Aug 1772 wanted creditors to show up or he was sending the lawyers after them. The upper right image above is a map from 1776 which shows the brewery on the point but does not name it. The map at the very top of the page was printed in France in 1777 from data collected in 1775 – it names it. Notice how the brewery appears to be strategically placed. Not only is it on the river so able to ship out directly, it is just north of the original site of Vauxhall Gardens, a privately run park for outings. It is just south of the Lispenard brewery also on the Greenwich Road. The area was described in testimony in the 1824 court case Bogardus v. Trinity Church in which the actual ownership of lands in the district were being disputed. One witness Benjamin M Brown described his recollection of the area:

At the period of his earliest recollection, there were but few houses in Chambers, Reade, or Barley (now Duane) streets, or in the lower part of Warren street, where it intersects the Greenwich road, now Greenwich street. North of Warren street was a hill, over which this road passed. After rising the hill, the first building on the west side was Harrison’s brewery, close to the North river, and in or about the block between Jay and Harrison streets. On the east side of the road, nearly opposite the brewery, was Speth’s oil mill, in or near Harrison street. The next improvement was Lispenard’s place of several acres of land, lying along the Greenwich road. His mansion house was east of and at some distance from the road, and near to what is now called Desbrosses street. North of Lispenard’s, was a tavern, a place of public resort, called Brannan’s Garden…

A near rural area of both industry and recreation it seems. The thumbnail to the upper right up there is another map, this from 1789 which again shows the facility to the south of Lispenard’s. The site continues to be associated with the family as noted in their Masonic history where we read that Harrison Street was among the streets named by the Vestry of Trinity Church in 1790, laid out by the Common Council in 1795, and deeded to the City by the church in 1802. The brewery and the lands was put up for sale in 1776 (actually 1775 – see below) but probably stayed in the family as they sold several lots at the site in 1824. In that last thumbnail to the lower right up there you can see that by 1803, the district has been leveled, regularized around the surveyor’s 90 degree angle with just an ornamental rectangle on the shore around where the point of land would have been. Quite charmingly, a Harrison Street still exists, crossing Greenwich at the site of the old brewery, now further inland with the fill from the Hudson river docklands. Houses on the street from the first decade of the 1800s still stand.

Update: A little more research a few days later tells a bit more of the story. Here is the notice in the New York Gazette from 27 March 1775:

But the property wasn’t sold. It stayed in family hands throughout the Revolution… well sort of.

On 21 March 1788, a letter was published in the

Daily Advertiser out of New York which set out a number of defences related to the character of various officials and in particular, Richard Harison, son of George. The anonymous author described how Richard took a neutral stance during the Revolutionary War. While he opposed the taxation imposed on the colonies, he feared the power of Great Britain and feared war would be a disaster. On the other hand he publicly declared early on that

“…he would take no part against this country… This conduct drew on him the resentment of the British, before the arrival of General Carleton, who with-held his house and brewery, at the North-River, for a long time, without paying for the same…

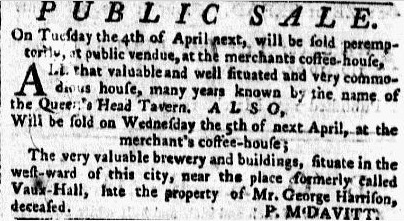

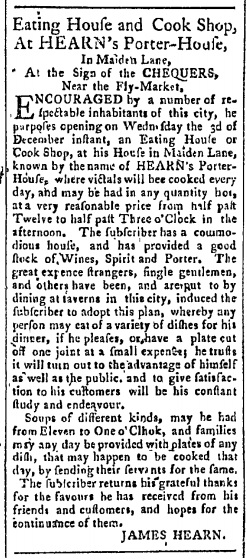

After the peace breaks out in 1784, there was one more kick at the can, one more attempt to make a go of it. Click on that thumbnail. Richard leases the brewery to Samuel Atlee who takes up brewing porter there. In the first weeks of 1785 he adds a pale “transparent” table ale. One of the principals behind the porter operation leaves in June 1785. The malthouse burned in October 1786 and Atlee’s enterprise comes to an end in late 1787 as this notice in the New York Packet of 11 December shows.

After the peace breaks out in 1784, there was one more kick at the can, one more attempt to make a go of it. Click on that thumbnail. Richard leases the brewery to Samuel Atlee who takes up brewing porter there. In the first weeks of 1785 he adds a pale “transparent” table ale. One of the principals behind the porter operation leaves in June 1785. The malthouse burned in October 1786 and Atlee’s enterprise comes to an end in late 1787 as this notice in the New York Packet of 11 December shows.

[End of Update….]

So a bit of an odd story. A fabulously large scale brewery with seemingly a very short original operating life, a few restarts and not much longer a physical existence. A Loyalist’s dream. “Harison’s folly” maybe even. But a late 1760s brewery built to brew likely at least 250 to 300 barrels a week or 12,000 to 15,000 barrels a year is quite the thing, quite the dream. In a market already well served by the Lispenards and Rutgers as well as Faulkner and Medcef Eden. And likely others. Did it succeed? The family’s other independent wealth makes it a bit hard to know. Wonder if the beer was any good.

¹Like me, a graduate from Kings College though I was over 200 years later after the College relocated to Nova Scotia with the Loyalists. The commander of the British troops in North America, His Excellency General Thomas Gage, did not attend my graduation nor did I, with my sole classmate and pal of John Jay, entertain the audience with a debate on “the subject of national poverty, opposed to national riches.” I did, however, party.

*Note if you are hunting this out, too, that Richard’s son is also George Harison and is also into land but now farther up into northern NY. Federalists are just, after all, pragmatic Loyalists.

** at page 115.

After writing my notes about

After writing my notes about

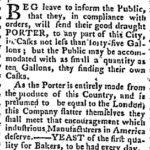

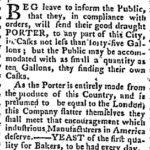

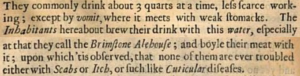

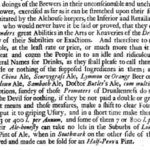

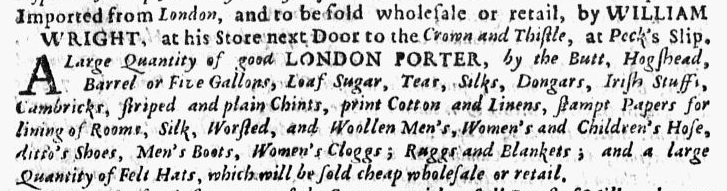

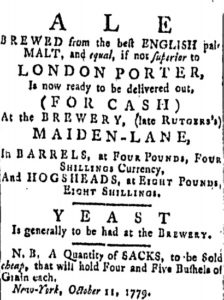

Jumping ahead, we find this ad from 1779 – the middle part of the war – which sets out some very interesting things. If you read it carefully, you will see it is not an ad for porter but an ad for a beer that is claimed to be as good as London’s porter. Imported porter is the standard to be met in the marketplace. The brewery is the

Jumping ahead, we find this ad from 1779 – the middle part of the war – which sets out some very interesting things. If you read it carefully, you will see it is not an ad for porter but an ad for a beer that is claimed to be as good as London’s porter. Imported porter is the standard to be met in the marketplace. The brewery is the