The latest project without all that much particular point is turning out to identify the brewers of New York City during the American Revolution aka the War of Independence. So far we have learned about:

– William D. Faulkner;

– The Lispenards; and

– The Rutgers.

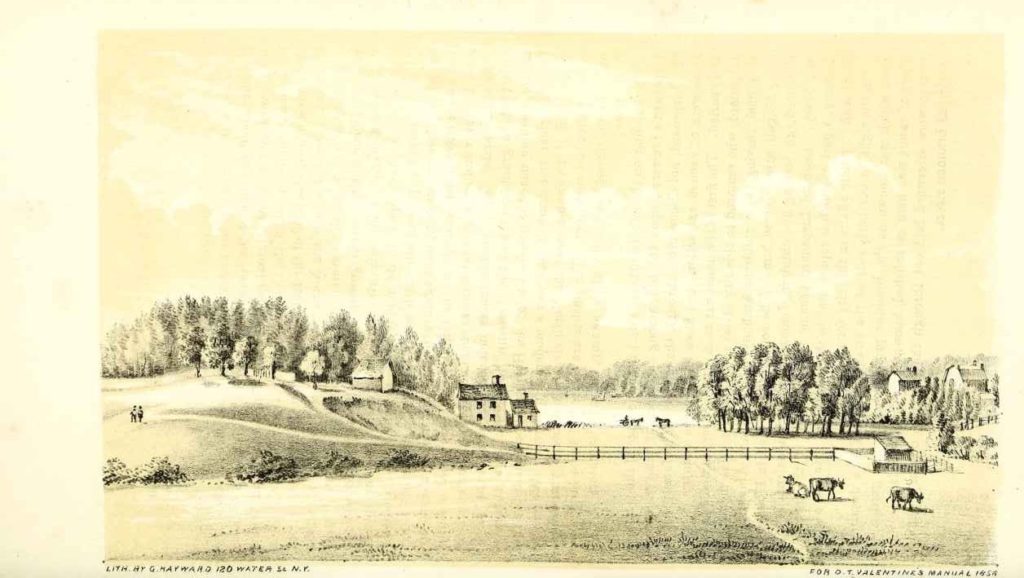

There are two more that I have noted so far, Harrison and Eden.¹ They are all located (if not all noted) on the clickable map above. A rather large version of the map for obsessive pouring over can also be found here. The breweries appear, as Craig predicted, to be lumped in distinct brewing areas. As we saw in Albany and is I suppose self-evident, these breweries were built near supplies of potable water. And while both New York and Albany are salt water seaports New York in the year 1775 is largely located on the lower tip of an island, Manhattan. Which means that fresh water comes at something of a premium. Important but I will get into that a bit more in a later post. Today it’s about Eden.

I hadn’t heard of this guy until I came upon this map of the Great Fire of 1776. In an essay recalling the world of New York in the early 1790s, we read:

At Number 26 Broadway, might have been daily seen the light-built but martial and elegant form of Alexander Hamilton, while his mortal foe, Aaron Burr, as we have stated, held his office in Partition street. John Jacob Astor was just becoming an established and solid business man, and dwelt at 223 Broadway, the present site of the Astor House, and which was one of the earliest purchases which led to the greatest landed estate in America. Robert Lenox lived in Broadway, near Trinity Church, and was building up that splendid commerce which has made his son one of the chief city capitalists. De Witt Clinton was a young and ambitious lawyer, full of promise, whose office (he was just elected Mayor) was Number 1 Broadway. Cadwallader D. Colden was pursuing his brilliant career, and might be found immersed in law at Number 59 Wall street. Such were the legal and political magnates of the day; while to slake the thirst of their excited followers, Medcef Eden brewed ale in Gold street, and Janeway carried on the same business in Magazine street; and his empty establishment became notorious, in later years, as the ‘ Old Brewery.’

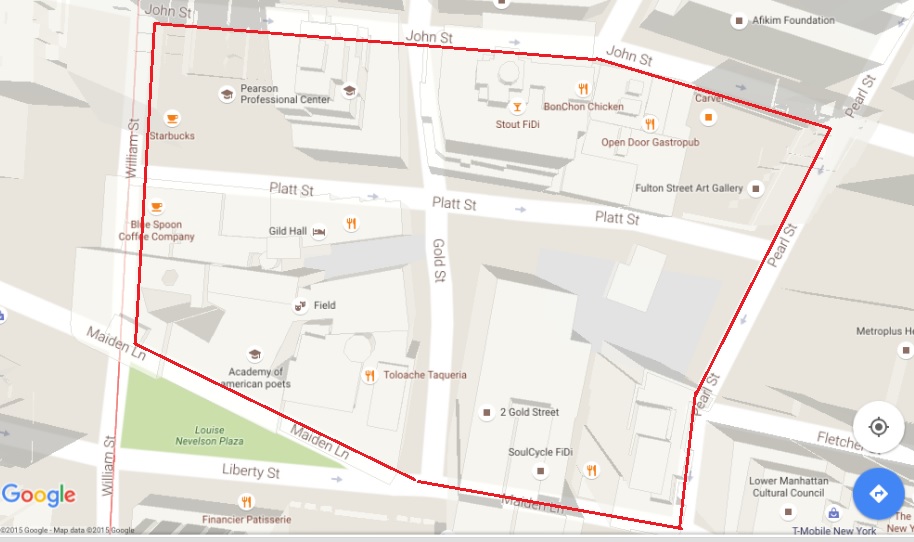

Janeway is a later story in time and an interesting one in its own right, also for another day. What is important today is that Medcaf Eden brewed ale in Gold Street. Long before I got interested in the antecedents of Canadian brewing in the Loyalist world before the American Revolution I fell for the excellent website “Forgotten New York” and, upon reading about Gold Street, I looked again to see if there was anything I could learn. Jackpot. Not only did was there a FNY a post from nine years ago about Gold Street, he had found Eden’s Alley leading from it. He even posted photos. Go have a quick look at the post.

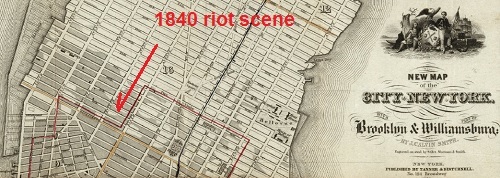

Now, click on the excellent FNY photo of the alley so I can point out a few things. So I can review. It is narrow. It is narrower than the narrowest bit of the photos of Gold Street see that? It’s narrower than the still narrow intersection of Beaver and Green Streets in Albany where in 1776 the King’s Arms was the flashpoint of the local insurrection. Eden’s Alley is that narrow because it is very likely not a street at all but the horse cart lane from Gold Street to the actual brewery. It’s probably the driveway. You can actually see it on the map of the 1776 fire. Check the red circle to the right of the other. Notice the break in street’s buildings at the circle’s 11 o’clock position? That’s Eden’s Alley. Notice how on the photo it leads east-ish according to the sun on the face of the north side wall. Parallel to Maiden Lane to the south where the competition in the form of one of Rutger’s breweries was located. See the bullet shaped carriage wheel bumper protecting the building’s corner from traffic pulling in from Gold Street? We have a few of those still in our old town. Notice another thing. It’s an uphill climb from Gold Street into the property of Medcef Eden. Because it’s built on uneven land. Because uneven land is next to the creeks and rivers where the fresh water was. What an excellent wee photo of an unappetizing back alley in one of the world’s great cities. Look at the topography on this map of NYC from 1783. You will find Golden Hill just inland above the “E” in east river. That hill? That’s what Eden’s Alley is climbing. FNY also traces the lane’s later history.

Now, click on the excellent FNY photo of the alley so I can point out a few things. So I can review. It is narrow. It is narrower than the narrowest bit of the photos of Gold Street see that? It’s narrower than the still narrow intersection of Beaver and Green Streets in Albany where in 1776 the King’s Arms was the flashpoint of the local insurrection. Eden’s Alley is that narrow because it is very likely not a street at all but the horse cart lane from Gold Street to the actual brewery. It’s probably the driveway. You can actually see it on the map of the 1776 fire. Check the red circle to the right of the other. Notice the break in street’s buildings at the circle’s 11 o’clock position? That’s Eden’s Alley. Notice how on the photo it leads east-ish according to the sun on the face of the north side wall. Parallel to Maiden Lane to the south where the competition in the form of one of Rutger’s breweries was located. See the bullet shaped carriage wheel bumper protecting the building’s corner from traffic pulling in from Gold Street? We have a few of those still in our old town. Notice another thing. It’s an uphill climb from Gold Street into the property of Medcef Eden. Because it’s built on uneven land. Because uneven land is next to the creeks and rivers where the fresh water was. What an excellent wee photo of an unappetizing back alley in one of the world’s great cities. Look at the topography on this map of NYC from 1783. You will find Golden Hill just inland above the “E” in east river. That hill? That’s what Eden’s Alley is climbing. FNY also traces the lane’s later history.

Medcef Eden passes away on 18 September 1798 leaving two sons, Joseph and Medcef Junior who die without children of their own. The will of Medcef Sr provided for this eventuality and, in doing so, tells us something about Eden’s origins.

It is my will and I do order and appoint, that if either of my said sons should depart this life without lawful issue, his share or part shall go to the survivor. And in case of both their deaths without lawful issue, then I give all the property aforesaid to my brother John Eden of Lofters, in Cleveland in Yorkshire; and my sister Hannah Johnson of Whitby, in Yorkshire, and their heirs.

Which means Medcef is very likely a Yorkshireman who immigrates to the new world leaving his own family behind. And what does he do between immigrating and expiring? He brews.

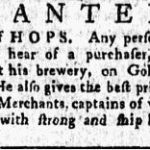

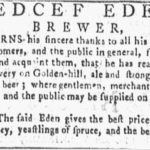

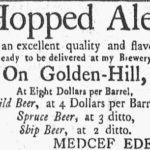

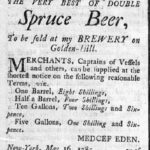

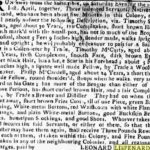

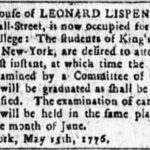

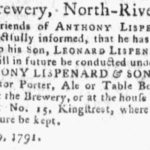

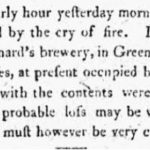

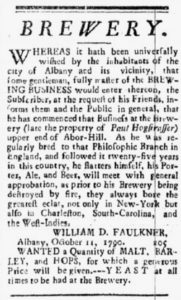

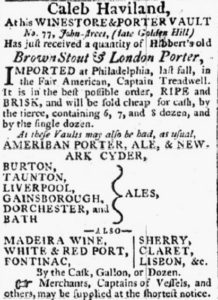

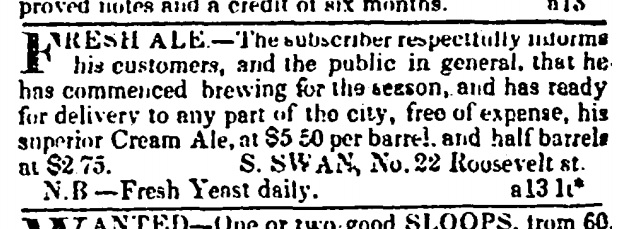

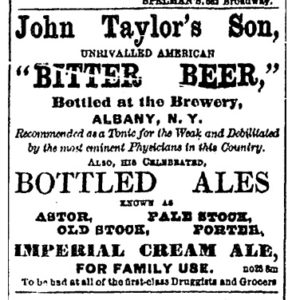

The ad to the upper left is from the The New York Gazette of 29 September 1777. Eden is buying hops and barley while selling strong and ships beer. In the upper middle ad from a year later on 2 November 1778 he is now selling four sorts of beer: ale and strong beer, ship’s beer and spruce beer. Almost three years later, the ad to the upper right from the The New York Gazette of 22 October 1781 focuses on his strong ale which he states “exceeds both in flavour and quality, any that has been brewed since the revolution.” By the time the lower left ad is placed in the New York Independent Journal of 1 June 1785, the war has been over for over a year and a half. He is selling double spruce beer, advertising rates by the barrel, half-barrel, ten gallon or five barrel. Finally, the ad to the lower right placed in the New York Daily Gazette from 21 June 1791 informs the public that George Appleby has taken over the brewing operations and is offering spruce beer, ship’s beer and others.

The immediate thing that strikes me is that Eden appears to have managed the transition from war to peace quite successfully. He stays on in the City during the Loyalist times and stays on after they leave and are replaced by the Revolutionaries. Just two month’s before the inevitable departure of the last of the British, according to the 22 September 1783 edition of the New York Gazette, Eden is buying barley. Eden’s neighbour, the widow Rutgers on Maiden Lane, left with the rest of the “popular party” as soon as the British showed up in 1776 – according to the 1784 court case over British use of her brewery during the war. Eden stays put.

There’s more to be found out of course even if in 1920, The New York Times could find no record of the brewery. Plenty of records likely no one other than a handful of masters students might have bothered looking at over the decades. But for starters that is an introduction to Medcef Eden – Yorkshireman, New Yorker and brewer.

¹Oops. One more. Robert Appleby, a spruce beer brewer on Catherine Street near the Ship Yards on the East River who advertised in the Royal New York Gazette on 19 April 1781.