As I was going through the blog posts shifting them over to the new platform for the past few months I realized that I’ve had tight waves of writing enthusiastically separated by other phases of, you know, treading water. If I had a topic to run with, a new database to explore I got at it. But I also skipped over some things. Failed to suck the marrow. I had in my head that I had a stand alone post on Mr. Bobin’s letter above from 1720 but in fact had only written this in one of my posts about the Rutgers brewing dynasty in New York City from the 1640s to the early 1800s:

As I was going through the blog posts shifting them over to the new platform for the past few months I realized that I’ve had tight waves of writing enthusiastically separated by other phases of, you know, treading water. If I had a topic to run with, a new database to explore I got at it. But I also skipped over some things. Failed to suck the marrow. I had in my head that I had a stand alone post on Mr. Bobin’s letter above from 1720 but in fact had only written this in one of my posts about the Rutgers brewing dynasty in New York City from the 1640s to the early 1800s:

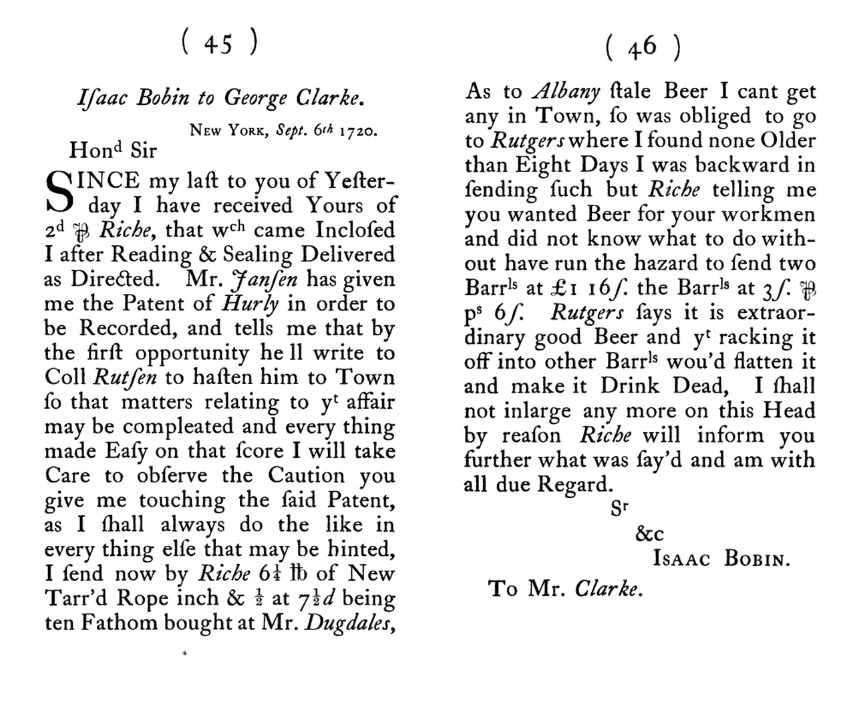

In a letter dated 6 September 1720 from Isaac Bobin to George Clarke we read:

…As to Albany stale Beer I cant get any in Town, so was obliged to go to Rutgers where I found none Older than Eight Days I was backward in sending such but Riche telling me you wanted Beer for your workmen and did not know what to do without have run the hazard to send two Barrels at £1 16/ the Barrels at 3/ and 6/. Rutgers says it is extraordinary good Beer and yet racking it off into other Barrels would flatten it and make it Drink Dead…

Isaac Bobin was the Private Secretary of Hon. George Clarke, Secretary of the Province of New York. So clearly Rutgers was as good as second to Albany stale for high society… or at least their workers. And in any case – we do not know if it was from Anthony’s brewery or Harman’s.

The Smithsonian has a better copy of the book of Bobin’s letters. What I didn’t get into were the details of the letter itself. Riche. Albany stale Beer. Drink Dead. Just what a whiner Bobin was. Riche? He seems to be the shipper, moving goods from the New York area to wherever the Hon. George Clarke was located. In another letter dated 15 September 1723, Clarke’s taste in fine good – including beer – is evident:

THERE goes now by Riche (upon whom I could not prevail to go sooner) a Barrel of Beef £1. 17f 6d; a Qr Cask of Wine @ £6; twelve pound of hard Soap @ 6£; twelve pd of Chocolat £1. if; two Barrls of Beer; a pd of Bohea Tea @ £ i.; Six qr of writing Paper. Will carryed with him from Mr. Lanes four Bottles of Brandy with a Letter from Mr. Lane.

In another letter dated 17 November 1719, beer and cider are being forwarded. Bobin’s job includes ensuring Clarke and his household has their drinks and treats. It all is very similar to the shipments for the colonial wealthy and well-placed we’ve seen half a century later from New York City to the empire’s Mohawk Valley frontier where Sir William Johnson received from the 1750s to 1770s: his beer from Mr. Lispenard, his imported Taunton ale and Newark cider .

I find the reference to stale in the 1720 letter interesting as it suggests a more sophisticated beer trade that merely making basic beer quickly and getting it out the door. Albany stale beer. Stale distinguishes as much as Albany does. Plus, Bobin compares to the “Albany stale” to the young Rutgers beer and seems to get in a muddle. What will the workers accept? Or is it perhaps that he is concerned what Clarke thinks the workers will accept. I worry about words like stale like I worry about the livers of the young beer communico-constulo class. We need to do better. Stale seems be a useful word in common usage for (exactly) yoinks but Martyn certainly places it, in the context of beer, as in use around the 1720s so Bobin’s usage is fairly current in England even if at the other side of the Atlantic Ocean. It’s thrown around generously in The London and Country Brewer in 1737 and used by Gervase Markham in the 1660s.

Aside from stale-ness, the dead-ness of the beer obviously is about its condition but why raking off is considered is unclear. Was it just at the wrong point in Rutger’s brewing process or was he operating his business by holding it in larger vessels and selling retail to his surrounding market, like the growler trade today? Again, not just any beer will do. In Samuel Child’s 1768 work Every Man His Own Brewer, Or, A Compendium of the English Brewery we see this passage referencing deadening at page 38:

It has been said before, what quantity of hops are requisite to each quarter of malt, and how the same are to be prepared; but here it must be considered that that if the beer is to be sent into a warmer climate in the cask, one third more hopping is absolutely necessary, or the increased heat will awaken the acid spirit of the malt, give it a prevalency over the corrective power of the hop, and ferment it into vinegar: to avoid this superior expence of hopping, the London and Bristol beers are usually drawn off and deadened, and then bottled for exportation; this really answers the purpose one way; but whether counterbalanced by charge of bottling and freight, &c. those who deal in this way can best determine.

Just bask in that passage for a moment. It’s (i) a contemporary that British beer was prepared for transport to warmer climates and (ii) among a few other techniques, the intentional deadening a beer followed by bottling was a technique used for export. Burton was, after all, brewed for export. As was Taunton for Jamaica’s plantations. The British simply shipped beer everywhere. IPA was not unique. Was there a beer brewed for Hong Kong that we’ve also forgotten about? Dunno. What we do know is that Bobin is saying is that Rutgers warns against a deadened beer for local use. Would he have been deadening beer for export? In 1720s New York City? We know that porter was shipped out of town later. We know that late in the century shipments of bottled porter were coming in.

Excellent stuff. I need to think about this more. But, like the seven doors of the Romantic poets, suffice it to say that a good record in itself can open up a wonderful opportunity to chase an idea. In an era of such early and falsely confident conclusion drawing, a useful reminder.