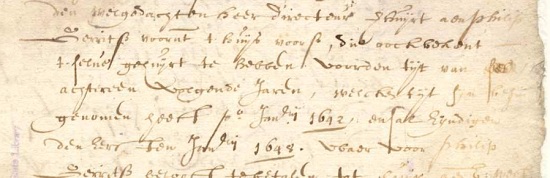

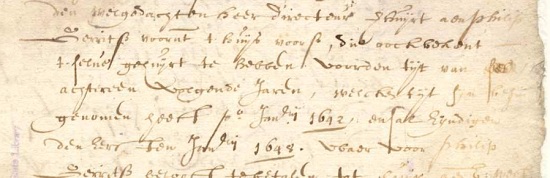

A portion of a 1640s lease to Philip Gerritsen of a house to be used as a tavern. Click.

A portion of a 1640s lease to Philip Gerritsen of a house to be used as a tavern. Click.

On the 22nd of March 1639, Cornelis van Tienhoven, secretary in New Netherland on behalf of the General Chartered West India Company received Gillis Pietersen van der Gouw, a 27 year old master carpenter who gave an account of the state of development in the colony by describing what buildings had been erected during Director Wouter van Twiller’s term on the island of Manhattan. Van der Gouw included in his report the building of an excellent barn, dwelling house, boat house and a brewery covered with tiles on farm No. 1. Van Twiller leased these lands in 1638 for two hundred and fifty Carolus guilders, payable yearly, together with the just sixth part of all the produce with which God shall bless the field. Beer would have been part of the produce.*

Director Van Twiller arrived in 1633 to run the colony in a time of great optimism and construction. The Hudson valley merchant community already had the character of an “independent sovereignty” more than a company doing business.

It owned one hundred and twenty vessels, ranging from three hundred to eight hundred tons burden, all fully armed and equipped; and employed between eight and nine thousand men. More than one hundred thousand guilders value in peltries were exported during the last year, and nearly the same quantity this year, from New Netherland. It is not surprising, then, that Van Twiller’s plans were on an extensive scale. The chief essential to the prosperity of the colony still lacked, nevertheless. Scarcely one solitary agricultural settler had been, as yet, sent over by the company, to fell the forest or reclaim the wilderness.**

The beginning of brewing on Farm No. 1 was the start of a relationship that lasted on those lands into the next two centuries. It ran directly north of the company’s garden outside the fort, from what is at present Wall-street, to Hudson-street, along Broadway in the city of New York; and went, in the time of the English, successively by the name of Duke’s farm, King’s farm, Queen’s farm. Now the site of Tribeca and the World Trade Center, it includes the lands developed in the first half of the 1700s by the Rutgers and Lispenard clan. It includes the 1760s export oriented brewery of Harison and Leadbetter and their successors into the 1800s before the good water disappeared. Legal right to the land meant control of the grain and the wealth brewing inevitably brings.

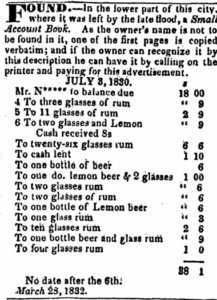

The reason for that long lasting success was, as it is today, the sensible regulation of brewing and beer consumption. Very early on in the New Netherlands experiment, the functions of grain growing, beer brewing and tavern keeping were separated and kept separate just as they were in the Netherlands. Then as now there was too much money and power inherent in the trade to allow it all under one hand. And there was too much danger in allowing it to all go unchecked. Yet, access to beer was a cultural key for the Dutch to the entire colonial undertaking. So, good laws were put in place. The most obvious sorts of laws are, like the above, the leases and transfers of land. Beer needs land. On 20 July 1638, Director General Kieft entered into a lease to one Jan Evertsen Bout for the New Netherlands Company’s farm at Pavonia in what is now New Jersey. The rents were quite specific:

For which Jan Evertsen aforesaid shall be bound yearly during the term of the lease to deliver to the aforesaid Mr. Kieft or his successor the fourth part of the crop, whether of wheat or other produce, with which God shall favor the soil; also every years two tuns of strong beer and twelve capons, free of all expense.

Brewing was part of the farming process. And sometimes too good a part of it to leave with the farmer. On 26 August 1641, Hendrick Jansen agreed to sell his property to Maryn Adriaensen. The sale included a house, barn and arable land plus a barrick all associated heriditaments together with all that is fastened by earth and nail. Excepted from the dead by were Jansen’s brew house and two brew kettels, which he was required to remove and take away “at his convenience and pleasure.”***

Just as the law recognized and protected who controlled the land and equipment that produced the beer, the law also regulated who sold the beer. Many of these sorts of laws still exist – like the laws regulating the distance a bar can be from a church and the rules about disturbing the peace during services. On 11 April 1641 the Council of New Netherlands heard the following case:

Whereas complaints are made to us that some of the Inhabitants here undertake to tap beer during divine service and also make use of small foreign measures, which tends to the neglect of religion and the ruin of this state; we, wishing to provide herein, do therefore ordain that no person shall attempt to tap beer or any other strong liquor during divine service, or use any other measures than those which are in common use at Amsterdam in Holland, or to tap for any person after ten o’clock at night, nor sell the vaen. or four pints, at a higher price than 8 stivers, on pain of forfeiture of the beer and payment of a fine of 25 guilders for the benefit of the fiscal and three months ‘ suspension of the privilege of tapping.****

This is not to say that the Dutch of New Netherlands were prudes. Far from it. Church events could be laden with alcohol. On 15 February 1700, the last of the church poor in Albany died – Ryseck, widow of Gerrit Swart. The “onkosten“ or expenses for the burial and ceremony borne by the community was recorded. The event seems to have been a social one. In addition to 150 sugar cakes and sufficient tobacco and pipes six gallons of Madeira were provided along with one of rum. In addition, twenty-seven guilders were paid by the congregation for a half vat and an anker of good beer. A similar table was set when Jan Huybertse passed away in February 1707. He was one of the “nooddruftige” or the needy and church coffers paid out for 3 gallons of wine, one of rum as well as 18 guilders for a vat of good beer. In each case, respects were paid by the local believing community with a good send off and a good drink for those in attendance.*****

Away from the church, the scenes could get more haphazard and needed locking down by municipal ordinance. Prices were fixed. On 16 January 1641 Cornelio vander Hoykens prosecuted Jan Tomasz and Philip Geraerdy for having sold beer for two stivers higher per gallon than was allowed.† On 25 August 1644, in making his defence to a prosecution that he did not pay the proper rate of excise tax on his beer, Philip Gerritsen raised the fact that a gang of sorts was at large who demanded cheaper beer. The week before the brewers declared on the record that if they voluntarily paid the three guilders on each barrel of beer, they would have the Eight Men and the community about their ears. In response, the council of New Netherlands banned harboring or even giving any food to the leaders of the Eight Men.†† The threat of violence, just as today, could play out within a tavern – as was seen on 14 March 1647 when Symon Boot met Piter Ebel:

…after the aforesaid persons had fought together, that a piece of Symon Root’s ear was cut off with a cutlass, whereof the aforesaid Symon Hoot In council demands a certificate In due form, In order that In the future, If necessary, he may make use thereof. Therefore, we, the director and council of New Netherland, [hereby certify that the ear was out off with the] cutlass In question in the place aforesaid. We request all those to whom this certificate may be shown to give full credence thereto. In token of the truth we have signed this and confirmed It with our pendent seal In red wax, this 14th of March, to wit, the certificate given to Symon Hoot.†††

Rather than leave it to the law of fist and knife, the Council required the giving of proper evidence to substantiate events as set out in the complaint. Order was imposed. A particular form of regulation related to violence was the troubled relationship the Dutch had before establishing peace and alliance with the local indigenous population, not helped in the slightest by Willem Kieft’s decision to attack them without any reasonable prospect of winning let alone actual sufficient cause. On 1 July 1647, the Council stated:

Whereas large quantities of strong liquors are dally sold to the Indians, whereby heretofore serious difficulties have arisen in this country, so that it is necessary to make timely provision therein; Therefore, we, the director general and council of New Netherland, forbid all tapsters and other inhabitants henceforth to sell, give or trade In any manner or under pretext whatsoever any beer or strong liquor to the Indians, or to have It fetched by the pail and thus to hand It the Indians by the third or fourth hand, directly or Indirectly, prohibiting them from doing so under penalty of five hundred Carolus guilders, and of being In addition responsible for the damage which might result therefrom. ††††

Things came to a point that early on in his term as Governor, Peter Stuyvesant made a general proclamation on 10 March 1648 respecting a wide range of they ways beer impose upon public order. No new ale-houses, taverns, nor tippling places could set up without council’s unanimous consent. Tavern keepers could not sell the businesses and had to immediately report all altercations. They could not “admit or entertain any company in the evening after the ringing of the curfew-bell, nor sell or tap beer or liquor to any one, travelers or boarders alone excepted, on Sunday before three o’clock in the afternoon, when divine service is finished, under the penalty thereto provided by law.” They were bound not to receive, directly or indirectly, into their houses or cellars any wines, beer or strong liquors before these are entered at the office of the receiver and a permit therefor has been received, under forfeit of their business and such beer or liquors and, in addition, a heavy fine at the discretion of the court.†††††

Notice how similar these laws from 370 years ago are to the sorts of regulation we see today. Not because the Dutch were puritanical or that the paranoia of a Randian was in anyway justified then as now. It’s because beer and taverns are both pervasive and a huge challenge to social order. Regulation and control not only are about ensuring taxes are paid and limbs go unbroken. While beer may be a consistent element of western culture, it is not all about sunny days on the middle class patios. And it’s an industry that generates massive economic wealth. So it is taxed. And it is controlled. Then and now. Because it is beer.

*Volume 1, Register of the Provincial Secretary, 1638–1642 (translation), pages 6, 108:

** History of New Netherlands: Or, New York Under the Dutch, Volume 1 by Edmund Bailey O’Callaghan, 1846, page 155-157.

***Volume 1, Register of the Provincial Secretary, 1638–1642 (translation), pages 72-73, 358-359:

****Volume 4, Council Minutes, 1638–1649 (translation) at page 106.

*****Upper Hudson Valley Beer, Gravina and McLeod, pages 35 to 36.

†Volume 4, Council Minutes, 1638–1649 (translation) at page 134.

††Volume 4, Council Minutes, 1638–1649 (translation) at page 235.

†††Volume 4, Council Minutes, 1638–1649 (translation) at pages 360-361.

††††Volume 4, Council Minutes, 1638–1649 (translation) at pages 380-381.

†††††Volume 4, Council Minutes, 1638–1649 (translation) at pages 496-500.

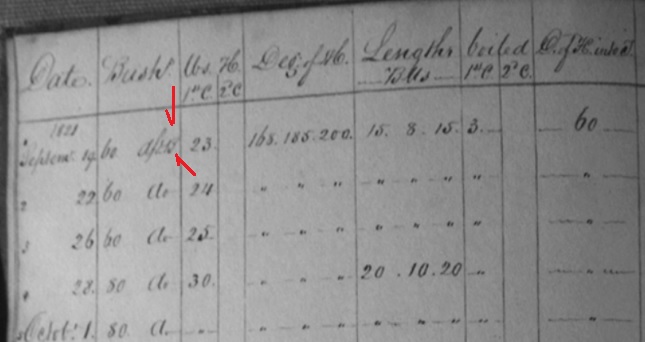

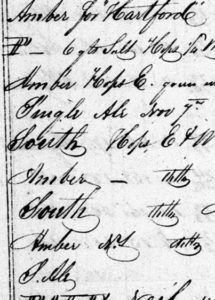

Brewing was seasonal in the early 1800s east coast towns. You see it in the Vassar logs from Poughkeepsie NY and again with the brewing logs of Francis and William Perot of Philadelphia of 1821-22. Ed Carson was good enough to scan them last fall and I am drawn back to them by

Brewing was seasonal in the early 1800s east coast towns. You see it in the Vassar logs from Poughkeepsie NY and again with the brewing logs of Francis and William Perot of Philadelphia of 1821-22. Ed Carson was good enough to scan them last fall and I am drawn back to them by

Yet, the future was now. Science was coming to agriculture in upstate New York. Ben Franklin’s

Yet, the future was now. Science was coming to agriculture in upstate New York. Ben Franklin’s

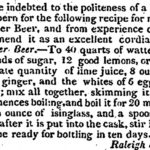

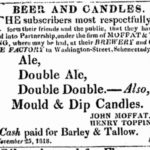

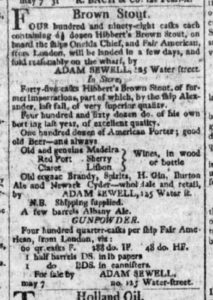

Next, Hibberts Brown Stout. This stuff is all over the place. Click on that thumbnail. That is a notice from just one store in 1805 stating that they have fifty-five casks on hand with another 498 casks on route. British beer brought in and in bulk. Broadly.

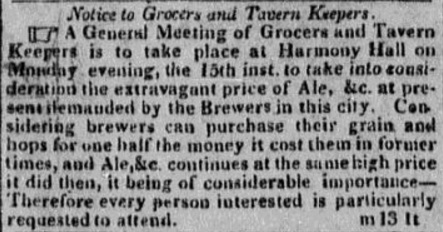

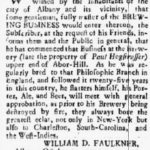

Next, Hibberts Brown Stout. This stuff is all over the place. Click on that thumbnail. That is a notice from just one store in 1805 stating that they have fifty-five casks on hand with another 498 casks on route. British beer brought in and in bulk. Broadly.  Plus, there’s southern beer. You see it in the logs. Click on the ad. Brewing was not practical below a certain latitude so brewers like William Faulkner of NYC and Albany shipped to South Carolina… and the West Indies. He died in 1792. Not to mention there was

Plus, there’s southern beer. You see it in the logs. Click on the ad. Brewing was not practical below a certain latitude so brewers like William Faulkner of NYC and Albany shipped to South Carolina… and the West Indies. He died in 1792. Not to mention there was  And it goes on and on –

And it goes on and on –