Before the curse that is social media was thrust upon us, one key promise of beer blogging was collective research. With the most welcome news that Lew is back into the beer blog game, he reminds us of the point of doing this day after day:

A bit over two years ago, I stopped writing this blog. It wasn’t because blogs are dead — I refuse to believe that — and it wasn’t because I got bored, and it certainly wasn’t because I was running out of things to say. Blogs, good blogs, relevant blogs still are vital, and they don’t have to be on Tumblr, or run through a microplane grater and splattered onto Twitter, or covered in kitties and posted on Facebook. Blogs are the place to do long-form writing, and I like to think I was able to balance somewhere between a tweet and tl;dr.

Even though I shared in the publication of two histories the year before, 2015 was the year I think I took my interest in brewing history most seriously. That few care about the state of brewing and porter selling in New York City in the decades around the Revolution is no concern of mine. It’s important just to write about it. Same with the centuries of brewing on Golden Lane and life in London, England’s district St. Giles’s Cripplegate. These things are interesting because they are true.

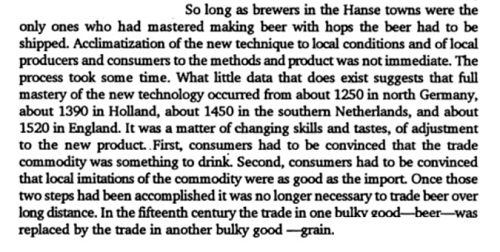

We are children of the Enlightenment. Three things we depend on for understanding were all invented and popularized in the 1700s: the application of science in practical matters, mass communications and commercial branding of products. Each is a means to create a lasting record, each a self-archiving activity. People are led to believe, as a result, that things prior to the advent of these phenomena were unlike today. No scientific brewing? No pale ale. No newspaper? No news. Folk actually believe these things. They believe folk didn’t know how to make fine things with available resources. We are slaves to records. We need to distrust them more even as we dive more deeply into them. Which leads us today’s new topic: Northdown ale. Never noticed the stuff until Jay tweeted this quotation from Pepys yesterday. Which got me looking for more information and found an excellent blog post from November 2014 posted on the excellently titled blog Things turned up by Sally Jeffery while looking for something else as well as this passage from a travel guide called All About Margate and Herne Bay reviewed an 1865 magazine named The Athenaeum:

Quoting largely from the Rev. John Lewis’s account of Margate, written in 1723, he notices the once famous beverage, known to Charles the Second’s thirsty subjects by the names of “Northdown Ale” and “Margate Ale” of which drink Lewis says, “About forty years ago, one Prince of this place drove a great trade here in brewing a particular sort of ale, which, from its being brewed at a place called Northdown in this parish, went by the name of Northdown Ale, and afterwards was called Margate Ale. But whether it’s owing to the art of brewing this liquor dying with the inventor of it, or the humour of the people altering to the liking the pale north-country ale better, the present brewers send little or none of what they call by the name of Margate ale, which is a great disadvantage to their trade.” This was the beer which Evelyn calls “a certain heady ale ” ; and it is probable that its popularity with London beer-drinkers influenced the generation of brewers who fixed the immutable properties of “stout.”

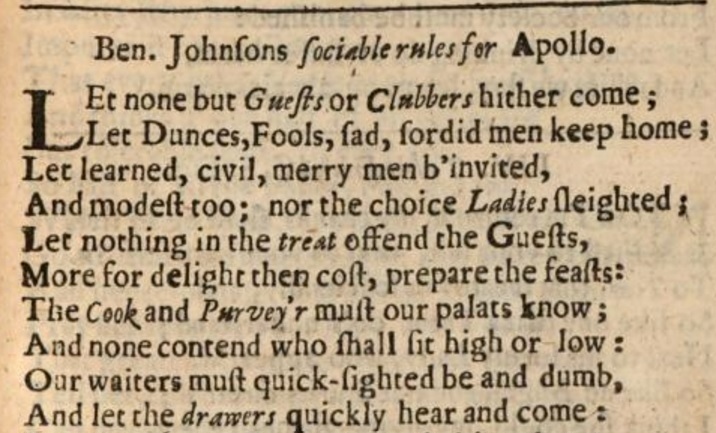

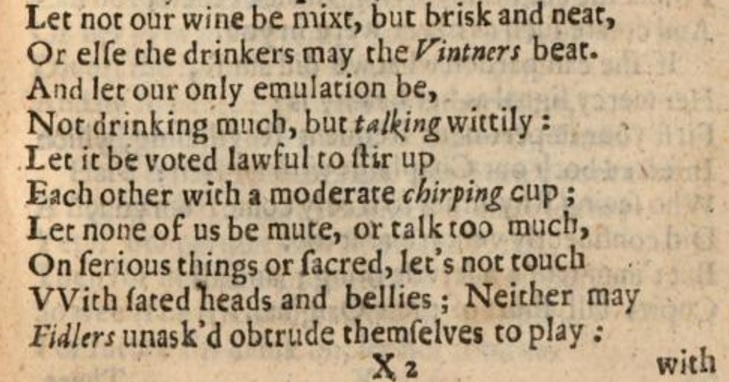

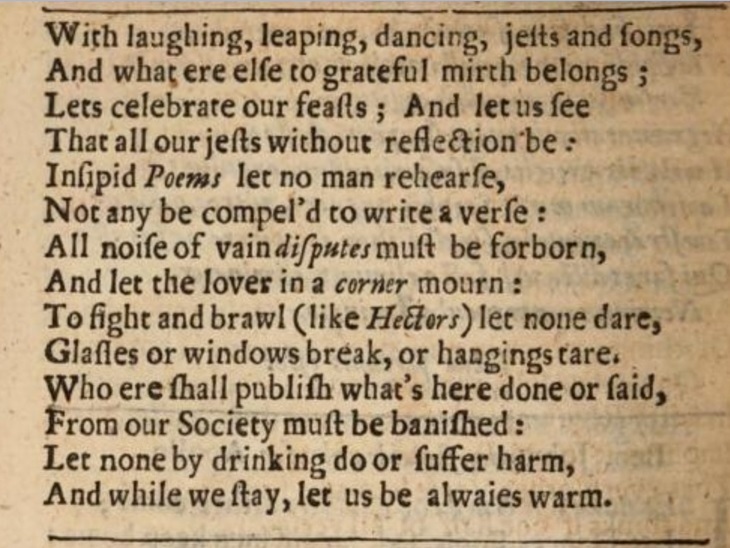

So, an 1865 citation of an account from 1723 recalling a drinking experience from forty years before that. Northdown Ale. In her blog post, Ms. Jeffery surveys the evidence and seeks to determine if she can “get a better idea of what the ale was like by looking at how it was made.” Let’s now see if we can add anything. First, I like the reference to Herrick. In one edition of his book, there is a footnote to another poet’s* line of verse anthologized in 1661: “For mornings draught your north-down ale / Will make you oylely as a Whale.” Pepys was drinking Northdown ale the year before. I am not sure why one might want to be so oily. Franklin referenced “he’s oil’d” in his 1730’s Drinker’s Dictionary. I am going to assume it means the beer is staggeringly strong for the moment. In The Curiosities of Ale & Beer: An Entertaining History from 1889, Herrick’s own lines on Northdown Ale from “A Hymne to the Lares”¹ are quoted:

The neighbouring county of Hereford, now a great cider-drinking locality, had in former times at least one town with a reputation for good ale. “Lemster bread and Weobley ale” had passed into a proverb before the seventeenth century. The saying seems, however, to have been affected chiefly by the inhabitants of the county, who, perhaps, were not quite impartial. Ray, writing in 1737, ventures to question the pre-eminence ascribed to the places mentioned. For wheat he gives Hesten, in Middlesex, “and for ale Derby town, and Northdown in the Isle of Thanet, Hull in Yorkshire, and Sandbich² in Cheshire, will scarcely give place to Weobley.” Herrick mentions this celebrated Northdown ale in the lines:—

That while the wassaile bowle here

With North-down ale doth troule² here,

No sillable doth fall here,

To marre the mirth at all here.

Did you see that? Wheat. Is this strong wheat ale? Or is that just a juxtaposition of two products of the region? Not sure. Likely the latter, given Jeffery’s references to an excellent but short lived barley malting trade concurrent with the height of Northdown ale’s prominence. Also, the diarist, botanist and courtier to Charles II John Evelyn describes being in Margate, one mile west of Northdown, on 19 May 1672 and states:

Went to Margate; and, the following day. was carried to see a gallant widow, brought up a farmeress, and I think of gigantic race, rich, comely, and exceedingly industrious. She put me in mind of Deborah and Abigail, her house was so plentifully stored with all manner of country provisions, all of her own growth, and all her conveniences so substantial, neat, and well understood; she herself so jolly and hospitable; and her land so trim and rarely husbanded, that it struck me with admiration at her economy. This town much consists of brewers of a certain heady ale, and they deal much in malt, etc. For the rest, it is raggedly built, and has an ill haven, with a small fort of little concernment, nor is the island well disciplined ; but as to the husbandry and rural part, far exceeding any part of England for the accurate culture of their ground, in which they exceed, even to curiosity and emulation.

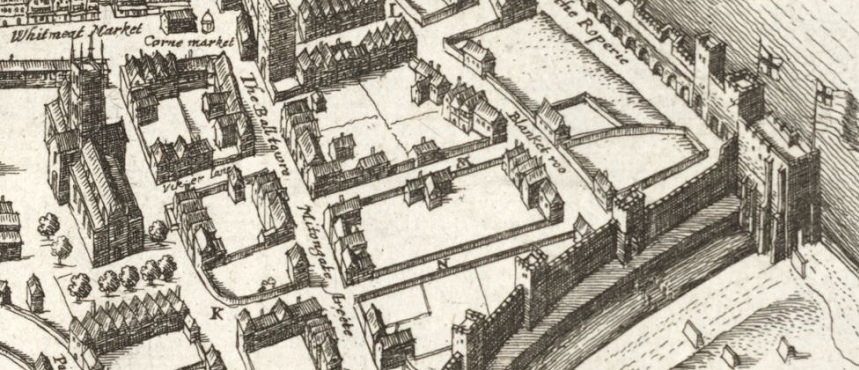

Which tells us there were many brewers and much malting in a rich farming district. And notice another thing from the quoted text further up. Thanet. Which reminds us to ask the particular question – where exactly is Northdown? That image above is from this map from 1711. If you click here you will see a supremely confusing cross-referencing of the 1711 map with a 1623 image on Jeffery’s post. See, before branding, newspapers and scientific brewing you needed to know where a beer or ale was from to figure out what to expect. Northdown is located in southeast England in the county of Kent – as in land of the noted hops. But the land of hops most noted about 200 years after Herrick wrote his lines. It was, also, the site of the October 2015 drinking session of the year as recorded by Team Stonch. So in the 1600s, the 1800s and the twenty-first century, a place of good beer but in each era quite distinct good beers.

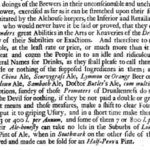

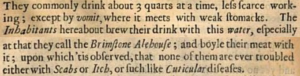

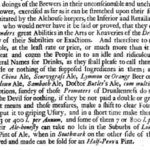

Click on that image to the right. It’s a paragraph from a 1681 treatise entitled Ursa major & minor: or, A sober and impartial enquiry into those pretended fears and jealousies of popery and arbitrary power, in a letter. Clearly an unhappy guy. But what he’s unhappy about is how, in tough economic times, brewers are making undue profits by not only jacking up prices but doing so by having “devised several name” for drinks including China ale, Hull ale – and Northdown ale. Sound familiar? Double the price for poorer beer? And you thought craft beer invented that trick. It appears to have been quite popular with the well placed in addition to the poets. John Donne – the Younger³ – recounts being sent a poem along with “a dosen bottles of Northdown ale and sack” which means it was good enough to bottle and, seeing as it was sent by Lord Lumley, good enough for the Peerage. Which might explain the jacked up price. A premium ale for those that can afford it.

Click on that image to the right. It’s a paragraph from a 1681 treatise entitled Ursa major & minor: or, A sober and impartial enquiry into those pretended fears and jealousies of popery and arbitrary power, in a letter. Clearly an unhappy guy. But what he’s unhappy about is how, in tough economic times, brewers are making undue profits by not only jacking up prices but doing so by having “devised several name” for drinks including China ale, Hull ale – and Northdown ale. Sound familiar? Double the price for poorer beer? And you thought craft beer invented that trick. It appears to have been quite popular with the well placed in addition to the poets. John Donne – the Younger³ – recounts being sent a poem along with “a dosen bottles of Northdown ale and sack” which means it was good enough to bottle and, seeing as it was sent by Lord Lumley, good enough for the Peerage. Which might explain the jacked up price. A premium ale for those that can afford it.

Notice one more thing. Sally Jeffery suggests there was indication that the ale was dark but also sees that “[t]he wheat stubble that is left is either mown for the use of the Malt-men to dry their Malt…” which, as we know, would make the sweetest, palest malt during that era. Enough to confirm anything? Nope. All we see from this set of records is clearly (i) a premium product, (ii) defined quite clearly to a time and place which was (iii) notably strong and (iv) bottled. The best ale during the Restoration? Maybe.

*Likely this John Phillips, royalist lad and nephew of Milton.

¹Here is the whole text of the poem:

It was, and still my care is,

To worship ye, the Lares,

With crowns of greenest parsley.

And garlick chives not scarcely:

For favours here to warme me,

And not by fire to harme me;

For gladding so my hearth here,

With inoffensive mirth here;

That while the wassaile bowle here

With North-down ale doth troule here,

No sillable doth fall here,

To marre the mirth at all here.

For which, o chimney-keepers!

(I dare not call ye sweepers)

So long as I am able

To keep a countrey-table,

Great be my fare, or small cheere,

I’le eat and drink up all here.

²I understand Sandbich to be “Sandbach” and troule means to “pass about.”

³“…an atheistical buffoon, a banterer, and a person of over free thoughts…”

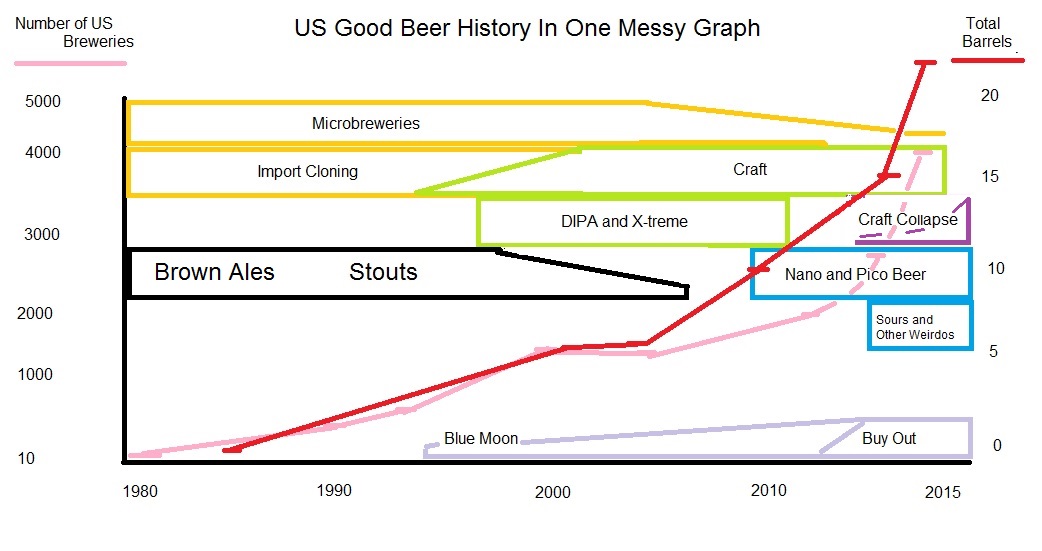

What an ugly diagram. Jeff posted a hypothesis to describe the last ten years in good beer and it caused me to come up with an ugly diagram. A scribbel. See, I don’t agree with him but I am not that concerned with agreeability. Not that I am not nice. I am nice as pie. But I just do not think he has it quite right. But that’s OK as we are all in this together. My issue is he awards one of those little gold foil stars that I use to see others get given at Sunday school. His conclusion:

What an ugly diagram. Jeff posted a hypothesis to describe the last ten years in good beer and it caused me to come up with an ugly diagram. A scribbel. See, I don’t agree with him but I am not that concerned with agreeability. Not that I am not nice. I am nice as pie. But I just do not think he has it quite right. But that’s OK as we are all in this together. My issue is he awards one of those little gold foil stars that I use to see others get given at Sunday school. His conclusion:

After writing my notes about

After writing my notes about