We have discussed Northdown ale before. One of the seventeenth century’s coastal ales that predate Burton’s arrival on the scene around 1712. Northdown of the strong ales that Locke described as “for sale” as opposed to home or estate use. But in that earlier Northdown post from, what, coming up on two years ago, most of the references to it are not contemporary to the 1600s. A lot of the discussion actually depends on one text, the 1723 The History and Antiquities of the Isle of Thanet by Rev John Lewis of Margate, which was itself then picked up in in an 1865 travel piece on Thanet published in The Athenaeum. To address that situation, I have been collecting more mid-seventeen century references over the weeks and months since then to do a better job of figuring out what was going on in the 1600s. One of the earliest I have found so far sits at the very helpful website Margate in Maps and Pictures compiled by one Anthony Lee, we read that in 1636:

We have discussed Northdown ale before. One of the seventeenth century’s coastal ales that predate Burton’s arrival on the scene around 1712. Northdown of the strong ales that Locke described as “for sale” as opposed to home or estate use. But in that earlier Northdown post from, what, coming up on two years ago, most of the references to it are not contemporary to the 1600s. A lot of the discussion actually depends on one text, the 1723 The History and Antiquities of the Isle of Thanet by Rev John Lewis of Margate, which was itself then picked up in in an 1865 travel piece on Thanet published in The Athenaeum. To address that situation, I have been collecting more mid-seventeen century references over the weeks and months since then to do a better job of figuring out what was going on in the 1600s. One of the earliest I have found so far sits at the very helpful website Margate in Maps and Pictures compiled by one Anthony Lee, we read that in 1636:

John Taylor reported ‘there is a Towne neere Margate in Kent, (in the Isle of Thanett) called Northdowne, which Towne hath ingrost much Fame, Wealth, and Reputation from the prevalent potencie of their Attractive Ale’.*

Part of that potency related to the health of one’s nether regions, specifically kidney stones. In The Art of Longevity, or, A Diæteticall Instition by Edmund Gayton (1608-1666) we read this passage:

What is ale good for? look against his doors,

And you shall see them rotted with ale-showrs:

It hath this speciall commendation,

To cleanse the ureter, and break the Stone:

Just as a feather-bed the flint doth break,

So th’ other stone your North-down-ale alike…

The author Gayton appears to have been Oxford educated as well as both an accomplished writer as well as a medical man. This work was published in 1659 and is described by the wiki-mind as “a verse description of the wholesomeness or otherwise of various foods.” The passage above is in chapter eight, “Of Ale”. There are chapters on wine as well as meath or metheglin and also beer:

Beer is a hop remov’d from ale, the hop

from a damn’d weed is a common crop…

I like the date of that work. That is two years before 1661’s publication in Wit and Drollery, Joviall Poems: Corrected and much amended, with Additions by the well known coded duo “Sir I. M. Ia. S” and “Sir W. D. I. D.” and the fabulous poem “On the Praise of Fat Men” in which we have the lovely lines which I only saw in a footnote before offering other healthful (or perhaps health-related) properties:

But now, for rules before we eat,

And how to chuse right battning meat,

For spoon-meat, barly-broth and jelly,

Very good is for the belly.

For mornings draught your north-down-ale**

Will make you oylely as a Whale;

But he that will not out flesh wit

Must at the good Canary sit;

For ’tis a saying very fine

Give me the fat mans wit in wine…

And, again, Northdown ale is the drink of the great and good. With a health related effect if not benefit. And, like those 1620s letters seeking September ale or beer for the Sir Horace Vere’s English delegation to the Netherlands, there are letters from Finch family files seeking shipments of Northdown to be sent to Constantinople in the 1670s where Sir John Finch was stationed as ambassador of England to the Ottoman Empire.

It is clear that in at least the second two-thirds of the 1600s, Northdown existed as one of a number of ales of note. It seems to transition into or also be known concurrently as “Margate” ale. This is perhaps due to that town expanding into and absorbing the neighbouring village of Northdown. It is now just a district next to Margate’s town centre. It could also be that Northdown ales were shipped from Margate to London. The article in The Athenaeum from 1865, mentioned above, also links the name change to the death of the brewer and land owner named John Prince whose Northdown was prized in the 1680s or at least until his death in 1687. Could he have been the brewer of the ales reported back in 1636? Maybe but unlikely.

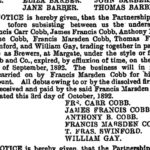

“Margate” hangs on as a descriptor of ale longer than most of its 1600s classmates mainly through the long success of Cobb’s Brewery. A brewery appears to have operated at the site from no later than the first decade of the 1700s. Cobb brewed there from 1760 through to the early 1800s when it owned 53 public houses and three farms and, then, for many decades thereafter. A second local brewery owned by the family from 1808 had a circular brew house. As The London Gazette of 11 October 1892 indicates, it returned to sole proprietorship from the 1890s to the 1937 when FM Cobb died in his 90s. The brewery sold Margate stout in the mid-1900s. The National Archive listings indicate that the sizable Cobb empire generated brewery records right up to 1967 right around when Whitbread bought it and shut it.

“Margate” hangs on as a descriptor of ale longer than most of its 1600s classmates mainly through the long success of Cobb’s Brewery. A brewery appears to have operated at the site from no later than the first decade of the 1700s. Cobb brewed there from 1760 through to the early 1800s when it owned 53 public houses and three farms and, then, for many decades thereafter. A second local brewery owned by the family from 1808 had a circular brew house. As The London Gazette of 11 October 1892 indicates, it returned to sole proprietorship from the 1890s to the 1937 when FM Cobb died in his 90s. The brewery sold Margate stout in the mid-1900s. The National Archive listings indicate that the sizable Cobb empire generated brewery records right up to 1967 right around when Whitbread bought it and shut it.

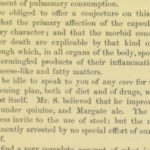

The term “Margate ale” is also used generically into the nineteenth century including in 1866’s Passages from the auto-biography of a “man of Kent” on the life of Robert Cowtan. It also appears in the 1869 book Mrs. Brown in London by one Arthur Sketchley. And if you click on the image to the right you will see a passage from 1871’s publication Lectures on the Principles and Practice of Physic as delivered at King’s College, London by Sir Thomas Watson in, likely, the 1830s. Like Gayton above, his fellow medical professional counterpart of two centuries before, no dummy. Later in life, a physician to Queen Victoria. And note that the “cure” he is speaking of, the thing that he cannot discount Margate ale helping with, is abdominal tumours. Jings. Could it really do that? Perhaps it just couldn’t hurt.

The term “Margate ale” is also used generically into the nineteenth century including in 1866’s Passages from the auto-biography of a “man of Kent” on the life of Robert Cowtan. It also appears in the 1869 book Mrs. Brown in London by one Arthur Sketchley. And if you click on the image to the right you will see a passage from 1871’s publication Lectures on the Principles and Practice of Physic as delivered at King’s College, London by Sir Thomas Watson in, likely, the 1830s. Like Gayton above, his fellow medical professional counterpart of two centuries before, no dummy. Later in life, a physician to Queen Victoria. And note that the “cure” he is speaking of, the thing that he cannot discount Margate ale helping with, is abdominal tumours. Jings. Could it really do that? Perhaps it just couldn’t hurt.

As noted, Northdown and Margate stood with other great ales. Consider this poem “The Praise of Hull Ale” which is unfortunately from a Victorian anthology from 1888, In Praise of Ale. The poems follows other that are more Elizabethan than Stuart but follows with the notation “here is a Yorkshire song of the same period, minus a few necessary excisions“! So, no promise that this is not a botched improvement on a more interesting original. Beware! That being said, note the range of beverages described in this most generous cutting and pasting.

Let’s wet the whisde of the muse

That sings the praise of every juice

This house affords for mortal use;

Which nobody can deny.

Here’s ale of Hull, which, ’tis well known,

Kept King and Keyser out of town,

Now it will never hurt the Crown;

Which nobody can deny.

Here’s Lambeth ale to cool the maw.

And beer as spruce as e’er you saw,

But mum as good as man can draw;

Which nobody can deny.

Here’s scholar that has doft his gown,

And donn’d his cloak and come to town.

Till all’s up, drunk his college down;

Which nobody can deny.

Here’s North down, which in many a case

Pulls all the blood into the face.***

Which blushing is a sign of grace;

Which nobody can deny.

Here’s that by some bold brandy hight,

Which Dutchmen use in case of fright.

Will make a coward for to fight;

Which nobody can deny.

Here’s China ale surpaaseth far

What Munden vents at Temple Bar,

‘Tis good for lords’ and ladies’ ware;

Which nobody can deny.

Here’s of Epsom will not fox

You more than what’s drawn from the cocks

Of Nuddleton yet cures smallpox;

Which nobody can deny.

For ease of heart, here’s that will do’t,

A liquor you may have to boot.

Invites you or the devil to’t;

Which nobody can deny.

That’s a quite a list. A list showing a wide variety of something that looks a lot like styles – and our darling Sammy Pepys drank it all. A quick search via Lord Goog for various phrases in his diary shows he records drinking Lambeth Ale on at least 8, 10 and 12 June 1661 as well as 27 April 1663. He had Northdown ale on 27 August and 13 September in 1660 as well as 1 January 1660/61. Margate ale is mentioned on 7 May, 27 August and 26 October in 1660. He had Hull Ale on 4 November 1660. He also had Derby ale and China ale. There are many references to Mum, buttered ale, wormwood ale. Bottled beer, too. In fact, he complains on 23 May 1666 of an eye ailment due to “my late change of my brewer, and having of 8s. beer.” A man of wide and varied taste. Notice, however, that there are no references to March ale or October ale according to the Google search. Is that correct? Maybe these were old fashioned labels by the 1660s.

Lambeth. Let’s look at this ale as a last consideration. We’ve written a bit about Hull ale before so, yes, let’s look at Lambeth. Well… except that in the 1670s the poet Andrew Marvel in his side gig as Member of Parliament for the city of Hull wrote a fair bit back to the municipal corporation about the taxation of beer. But set that aside. Let’s look at Lambeth. One problem as Martyn mentioned over at Facebook: “It’s a bit of a mystery where Lambeth Ale was actually brewed.” If you click on that image you will see one reason why. It’s a map from the 1720 edition of Stow and Strype – and even at that time Lambeth was mainly filled with fields and physically distinct from the actual City of London. Consider this painting from the 1680s by F.W. Smith. Open grounds down to the Thames sit all around Lambeth Palace, London residence of the Archbishop of Canterbury. Where’s the brewery?

Lambeth. Let’s look at this ale as a last consideration. We’ve written a bit about Hull ale before so, yes, let’s look at Lambeth. Well… except that in the 1670s the poet Andrew Marvel in his side gig as Member of Parliament for the city of Hull wrote a fair bit back to the municipal corporation about the taxation of beer. But set that aside. Let’s look at Lambeth. One problem as Martyn mentioned over at Facebook: “It’s a bit of a mystery where Lambeth Ale was actually brewed.” If you click on that image you will see one reason why. It’s a map from the 1720 edition of Stow and Strype – and even at that time Lambeth was mainly filled with fields and physically distinct from the actual City of London. Consider this painting from the 1680s by F.W. Smith. Open grounds down to the Thames sit all around Lambeth Palace, London residence of the Archbishop of Canterbury. Where’s the brewery?

Perhaps it will help to discuss what Lambeth isn’t. First, it isn’t a brewing scene that seems to continue. As I mentioned in the Locke post the other day, Lambeth is noted in a 1939 book Prices and Wages in England**** covering 1500 to 1900 but it was specified as a type of beer in 1708. The references to Lambeth are found in relationship to Lord Steward’s accounts, royal court records of ale and beer purchases from the late 1600s through the 1700s. Lambeth ends in 1708 in one sense because there is no equivalent of the Cobb family as in Margate that continues and builds upon a 1600s legacy well into the 1800s. Lambeth did have later great breweries in the 1800s including the joint stock British Ale Brewery of 1807 on Church Street to the south of the palace and the Red Lion Brewery built on the site of the Belvedere pleasure gardens in the 1830s but there seems to be no continuity to the use of the words “Lambeth ale” in the 1600s.

“Lambeth ale” is also not a euphemism for London beer. Lambeth ale was brought into London itself. Lambeth is not only physically distinct,***** it is purposefully distinct. It is the ecclesiastical centre. In the 1670s it sits in view of Westminster, seat of secular power both royal and Parliamentary, to the north and across the river. London had its own brewers who we have discussed before. There is the brewing at dodgy and somewhat inland Golden Lane near Cripplegate that extended from the medieval to the Nazi bombings including the Golden Lane brewery of the 1700s. There is also beer to be bought from John Reynonds of London as the Hudson Bay Company did in the 1670s. The City of London itself had its own contemporary brewers separate and distinct from those of Lambeth.

So “Lambeth” is not a fuzzy euphemism for brewing in and around London. It is not Lambeth Hill. Lambeth proper is a bit upriver. Cleaner water. Charles II swam there. And you might think spiritually purer, too. This is an odd thing. Lambeth of the last third of the 1600s seems to have a spicy reputation… though perhaps where in London didn’t. It is the era just after the Restoration of the monarchy as well as the time of the restoration of London after the Great Fire of 1666. The end of Puritanism. In The Journal of Brewery History 135 (2010) we find the article, “Women, Ale and Company in Early Modern London” by Tim Reinke-Williams we learn about a ballad from around 1680, Five Merry wives of Lambeth, which tells how Sarah, Sue, Mary, Nan and Nell “lov’d good Wine, good Ale, and eke good chear” which beings with and is subtitled:

Five wanton wives at Lambeth liv’d I hear which lov’d good wine, good ale, and eke good chear, and something in a corner they would take for which they went abroad to merry make and what they did, if you will but draw near the full conclusion you shall quickly hear.

Wanton! Deary me. Bawdy maybe lower class lewd encounters! It was a multi-purpose zone. In 1648, Parliament placed a garrison and prison in Lambeth House which they also used as a prison. With the Restoration, came the rebuilding of Lambeth Palace as viewed by Pepys in 1665 but still he went there to gypsy fortune-tellers in 1668. Vauxhall Gardens were also newly developed nearby during that same decade. There was a tavern with ale and, err, bawdy upper class lewd encounters.

So, at this point, a couple of ideas strike me. Lambeth ale may be multi-sourced ale from the zone of sauciness well known to those in London. Think Coney Island. It could actually, on the other hand, be ale brewed in connection to the Palace. Could it be there are either brewing accounts or brewing records confirming if the Archibishop was a buyer or seller of ale? It could, of course, be something else. Who knows? Stuff for the comments and future posts.

Let’s go back to Locke. In this post all I have done is unpacked and organized what he called “ale for sale” – the 1600s English ales with a city in the title. Two things happen soon thereafter. Things change and, if we obey chronology, things that were not likely anticipated. Burton and porter. Behemoth and Leviathan. Brewing at a greater scale and at an industrial pace is coming with the new century.

——–

Your footnotes attached to today’s reading:

*from John Taylor’s book, The honorable, and memorable foundations, erections, raisings, and ruines, of divers cities, townes, castles, and other pieces of antiquitie, within ten shires and counties of this kingdome namely, Kent, Sussex, Hampshire, Surrey, Barkshire, Essex, Middlesex, Hartfordshire, Buckinghamshire, and Oxfordshire: with the description of many famous accidents that have happened, in divers places in the said counties. Also, a relation of the wine tavernes either by their signes, or names of the persons that allow, or keepe them, in, and throughout the said severall shires, Printed for Henry Gosson, London, 1636.

**Do you see the common problem for the poor amateur beer historian? In each case it is spelled “N/north-down-ale” and not Northdown ale. That’s the real curse of the digital era, Lord Good’s lack of lateralism consideration.

***So, keeping score, it flushes the face full of grace, gets you oily as a whale and breaks down kidney stones.

****Reader Brian Welch was kind enough to scan a few pages from a copy at a library at Harvard.

It appears that after the restoration of Charles II, accounts of expenditures were required if Parliament was to pay for them. Which is why the records mainly begin in 1659. They continue to 1812 and include all beer and ale stored in the palace butteries Pretty good record. They include “bonfire ale” which is ales for bonfires which may be public event where the royals pay for the ale as opposed for ales for the royal households themselves.

*****One traveled to Lambeth. Pepys got there by coach, by horse and by boat and even by foot over the ice. It was “near” rather than “here” for those describing it in the late 1600s.

I’d have thought that there’s a fair chance the origins lay with the church, given the history of ecclesiastical brewing. Separate from that, Church lands were often associated with “fun” as they were not subject to civil law, so you often got theatres and such like that were banned in the main cities. There’s an interesting comparison with the South Bank in London – prostitutes were known as “Winchester geese” because they were licensed by the Bishop of Westminster to ply their trade on his land west of Borough Market, safe from the civil authorities. The Globe Theatre was built a bit further west in 1599, and the Anchor brewery started in 1616 – it subsequently became the headquarters of Barclay Perkins. The Puritans closed down all the theatres in 1642 and I imagine Lambeth grew up as a “thing” after the Restoration because the South Bank had been redeveloped.

Plus, after the fire, the City is gutted and must have been for years. Lambeth, however, is well established before 1666 so it isn’t caused by the fire. The crypt of the Palace is stil intact and apparently was the holding room for eclesiatical beer and wine before the Reformation. So who knows? Maybe there was a great brewery built into the operation that also sold to the public out the back door?

City was – but that didn’t affect the South Bank.

I don’t know, but was Lambeth a small thing that then really blew up after the Restoration?

I think it’s fair to assume that there was some kind of brewing associated with the Palace, the question is more whether that was the brewery that drove the reputation of “Lambeth beer” or whether it was an independent operation.

Two quick points: Lambeth Palace certainly had a brewery, which may have been in operation as late as the 1720s, but I can’t see it making ale for sale; and it was the Lion brewery in Belvedere Road, not the Red Lion brewery.

Hi Martyn,

I appear to have picked the far less popular name for the Lion Brewery but still a name.

I think it is possible that Lambeth ale could have been produced by the Palace BUT at the critical point its not there to brew even if it wanted to be. Pepys witnesses the rebuilding of Lambeth Palace after the restoration.

The tune for “In Praise of Ale” !