It is obviously a tough time here in Ontario and in Canada. The mass murder on Yonge Street in Toronto on Monday has struck hard and will affect many for years to come. It has come so soon after the Humboldt tragedy. And for our house, a neighbour – dearly liked, always been good to the kids – passed suddenly. It’s a rotten end to a hard winter. Ten days we were in a two day ice storm and now suddenly it’s warm. It’s a hard segue, like any sudden transition. Yet when I read Jon Abernathy’s thoughtful warm memorial to his own father who also passed away recently again with little warning, we are certainly reminded there are bigger things in life than beer yet – as Jon put it – it’s hard but we are doing OK. I hope.

So, this weeks links are offered to give some lighter thoughts. One delightful small thing I saw this last week is this tiny 12 inch by 12 inch true to scale diorama of the old Bar Volo on that same Yonge Street in Toronto. It was created by Stephen Gardiner of the most honestly named blog Musings on my Model Railroading Addition. I wrote about Volo in 2006 and again in 2009. It lives on in Birreria Volo but the original was one of the bastions, a crucible for the good beer movement in North America. The post is largely a photo essay of wonderful images like the one I have place just above. Click on that for more detail and then go to the post for more loveliness.

So, this weeks links are offered to give some lighter thoughts. One delightful small thing I saw this last week is this tiny 12 inch by 12 inch true to scale diorama of the old Bar Volo on that same Yonge Street in Toronto. It was created by Stephen Gardiner of the most honestly named blog Musings on my Model Railroading Addition. I wrote about Volo in 2006 and again in 2009. It lives on in Birreria Volo but the original was one of the bastions, a crucible for the good beer movement in North America. The post is largely a photo essay of wonderful images like the one I have place just above. Click on that for more detail and then go to the post for more loveliness.

In Britain, after last week’s AGM of CAMRA there has been much written about the near miss vote which upheld the organization’s priority focus on traditional cask ale. Compounding the unhappiness is the fact that 72% voted for change – but the change needed 75% support from the membership. Roger Protz took comfort in how high the vote in favour of change actually was. Pete Brown took the news hard, tweeting “cask ale volume is in freefall.” He detailed his thoughts in an extended post. And B+B survey the response and look to the upsides that slowly paced shifts offer. The Tandly thoughts were telling, too. While it is not my organization, I continued to be impressed by the democratic nature of CAMRA, the focus on the view of consumers rather than brewers as well as the respect for tradition. I am sure it will survive as much as I am sure that change will continue, even if perhaps at an increasing pace and likely in directions we cannot anticipate. Q1: why must there be only the one point of view “all good beer all together” in these things? Q2: in whose interest is it that there is only that one point of view?

While I appreciate I should not expect to link to something wonderfully cheering from Lars every week, I cannot help myself with his fabulously titled post, “Roaring the Beer.” In it he undertakes a simple experiment with a pot and rediscovers a celebratory approach to sharing beer that is hundreds of years old. Try it out for yourself.

Strange news from Central Europe: “In 2017, the Czech on average drank 138 litres over the course of the year, the lowest consumption in 50 years.” No doubt the trade commentators will argue self-comfortingly “less but better!” while others will see “less but… no, just less.” Because of course there’s already no better when we’re talking about Czech lager, right?*

As a pew sitting Presbyterian and follower of the Greenock Morton, I found this post at Beer Compurgation very interesting, comparing the use of Christian images in beer branding (usually untheologically) to the current treatment of other cultural themes:

To try and best create an equivalence I have previously compared being a Christian in modern England to being a Scottish football fan in modern England… On learning your love for Scottish football people in general conversation would automatically make two assumptions:

a) You believe domestic Scottish football to be as good as domestic English football;

b) You believe Rangers and Celtic (The Old Firm) are capable of competing for the English Premier League title…

The accusations and derision came from assumptions of your beliefs and the discussions would continue this way even after explaining that their conjectures were false. Talking about Christianity here is similar. By existing I am allowed to be challenged directly about my thoughts on sexuality, creationism, mosaic period text, etc.. and people often assume they understand my attitudes beforehand.

Personally, I think the Jesus branding is tedious bu,t thankfully, all transgressors all go to hell to burn forever in the eternal fires… so it’s all working out!

Homage at Fuggled to the seven buck king.

Question: what am I talking about in this tweet?

Hmm. Oh yes! The news that Brewdog is claiming they have brought back Allsopp India Pale Ale. First, it appears that someone else has already brought it back. Weird. Second, as was noted by the good Dr. David Turner last year, this can only serve as a marketing swerve for the hipsters. AKA phony baloney. Apparently, the lads have been quietly cornering the market in some remarkable intellectual property including, fabulously, spontaneity! My point is this. You can’t recreate a 1700s ale until there is 1700s malt barley and a 1700s strain of hops. [Related.] Currently, I would say we can turn the clock back to about 1820 if we are lucky given the return of Chevallier and Farnham White Bine. There is no Battledore crop and I couldn’t tell you what the hops might be even though there was clearly a large scale commercial hop industry in the 1700s, not to mention in the 1600s the demands of Derby ale and the Sunday roads “full of troops of workmen with their scythes and sickles,”. The past is a foreign land, unexplored. Perhaps Brewdog have found a wormhole in time that has now overcome that. Doubt it but good luck to them.

Hmm. Oh yes! The news that Brewdog is claiming they have brought back Allsopp India Pale Ale. First, it appears that someone else has already brought it back. Weird. Second, as was noted by the good Dr. David Turner last year, this can only serve as a marketing swerve for the hipsters. AKA phony baloney. Apparently, the lads have been quietly cornering the market in some remarkable intellectual property including, fabulously, spontaneity! My point is this. You can’t recreate a 1700s ale until there is 1700s malt barley and a 1700s strain of hops. [Related.] Currently, I would say we can turn the clock back to about 1820 if we are lucky given the return of Chevallier and Farnham White Bine. There is no Battledore crop and I couldn’t tell you what the hops might be even though there was clearly a large scale commercial hop industry in the 1700s, not to mention in the 1600s the demands of Derby ale and the Sunday roads “full of troops of workmen with their scythes and sickles,”. The past is a foreign land, unexplored. Perhaps Brewdog have found a wormhole in time that has now overcome that. Doubt it but good luck to them.

Well, that’s likely enough for this week. Remember to check in with Boak and Bailey on Saturday and then Stan on Monday for their favourite stories and news of the week that was.

*Note: see also the work of CAMRA and the protection of cask ale.

Stan responded in his flickering light bulb of a blog’s Monday links commenting “[b]ut that’s not the rabbit hole. Authenticity is the rabbit hole.” He went so far as to shout out in dispair, even in paranthetically “[i]t might be time to bring back the

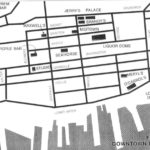

Stan responded in his flickering light bulb of a blog’s Monday links commenting “[b]ut that’s not the rabbit hole. Authenticity is the rabbit hole.” He went so far as to shout out in dispair, even in paranthetically “[i]t might be time to bring back the  The Hall study has a number of other tidbits of information that frame the downtown scene, starting with this map. I kid myself that I could sketch this blind folded in a isolation tank but most of the locations pop back to mind immediately. The map also illustrates the general university student flow from southwest to north east, the march many evenings being from Your Father’s Mustache to the Lower Deck. And there is a concise description of what “draft” was:

The Hall study has a number of other tidbits of information that frame the downtown scene, starting with this map. I kid myself that I could sketch this blind folded in a isolation tank but most of the locations pop back to mind immediately. The map also illustrates the general university student flow from southwest to north east, the march many evenings being from Your Father’s Mustache to the Lower Deck. And there is a concise description of what “draft” was: