It’s not like I dislike office work. It’s just that I like a week off in summer better. Drove too much. About 2500 km all in all. Did home repairs and lawn stuff. Took trousers to the tailor. Visited a tiny new brewery. Yes, that one right there. I expect to post on the beers I dragged home hidden amongst the kids’ camp and cottage crap. What else went on this week?

It’s not like I dislike office work. It’s just that I like a week off in summer better. Drove too much. About 2500 km all in all. Did home repairs and lawn stuff. Took trousers to the tailor. Visited a tiny new brewery. Yes, that one right there. I expect to post on the beers I dragged home hidden amongst the kids’ camp and cottage crap. What else went on this week?

Flying Dog Quits The Brewers Association

The recently Maryland-based brewery Flying Dog announced it had quit the Brewers Association and folk quickly took sides or at least thought a bit about which side they might take. Nothing better than when libertarians and progressives face off over something even though the both have a thing for tie-die shirts. The press release is pretty clear about what’s behind the move:

The BA’s new Marketing & Advertising Code is nothing more than a blatant attempt to bully and intimidate craft brewers into self-censorship and to only create labels that are acceptable to the management and directors of the BA. By contrast, Flying Dog believes that consumers are intelligent enough to decide for themselves what choices are right for them: What books to read, movies to watch, music to listen to, or beers to consume (and whether or not they like the labeling).

What’s really interesting about this is how it is tied in as part of the new optional (and seemingly stalled at about 20-25% buy-in) logo thing. And… freedom!!! Or just licence… or debauchery… or something co-opted. J. Notte summed it up this way on Sunday: “BA sees itself as a parent setting the rules, Flying Dog sees BA as a roommate who just set a fire in the living room.” What I don’t understand was where the BA membership outreach and committee work was on the logo and the code of conduct? Was this all actually just imposed without any trial balloons? More to the point, will others quit, too?

The Economist Noticed Craft Beer!!!

I found this story entitled “Craft Beer in America Goes Flat” interesting, pretty cool in fact as The Economist isn’t this micro focused [Ed.: get it? An economics pun!!] usually but it gets to the point: “the number of brands has proliferated, the number of drinkers has not.” [Ed.: sweet attention to that verb structure, too.] It might have been a link for last week but the lack of chit chat about the story since it came out is interesting in itself. I am sure if we ever see a retraction in US craft beer we’ll have months and months and months of explanation of how it’s not a retraction from all the smart people with careers invested in the expansion of US craft beer.

Why Even Call It “Contract Brewing”?

Ben Johnson expanded on his article in Canada’s newspaper, The Old and Stale, with a blog post that unpacks the contract beer situation in a pretty clearheaded manner. Me? I take nothing from the argument that consumers don’t care given that labeling laws don’t require that anyone tell consumers that a beer is brewed somewhere that isn’t the little sweet Grannie’s cottage the branding would make you think… but the other arguments are pretty good.

Let’s be clear. The firm that brews the beer bought on a contract is a “contract brewer.” Other folk in the retail supply chain are maybe a “beer company.” Nothing wrong with being a beer company. Also, it obeys English as one who does not brew can’t also be brewing. Doubt me? Ask one of them to change the yeast strain to improve the batch. Oh, not allowed. By whom? Oh, the actual brewer.

And the Co-opting Of “Punk” Started A Decade Ago

Good to see, as reported by Matt C., a Sussex-based brewery Burning Sky… a wee actual-ish crafty brewery has back away from BrewDog’s weird insistence that they are somehow connected to “punk.” [Ed.: they are only getting that in 2017? It’s like your nerdy accountant cousin Ken who likes to pretend he gets that hop-hip all the kids are listening to.] Anyway, BrewDog is great at marketing, aiming to be wonderful at opening branch plants globally as well as a chain of bars and half their beers are even sorta OK. But, let’s be honest, it’s hardly craft anymore let alone punk. A fledgling lawyer and his pal, a very successful brewer, dreamed up a way to get rich through beer with a smidgen less – what? – less of something… than even Malcolm McLaren‘s relationship to the actual invention of punk. Tellingly, Matt could only find a managing director for the BrewDog bars division to get a quote from. Small. Traditional. That’s it. Keep in line. Punks do that. Keep. In. Line. And… err… something co-opted.

Other Things of Great Importance

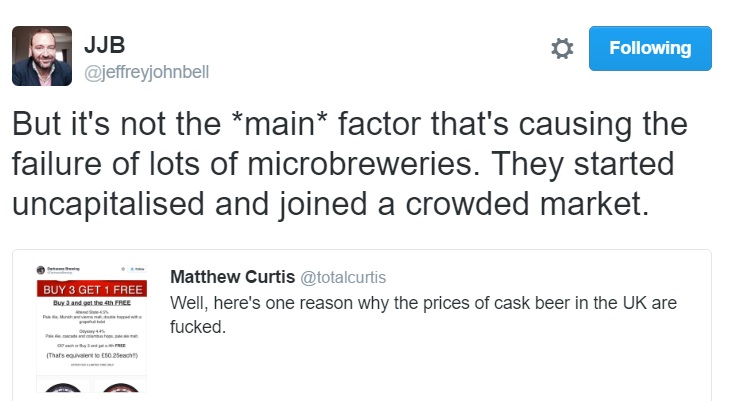

Jeff Bell posted a lovely short vignette of an encounter on the streets of London with a man sharing his beer.

Tweet of the week? From Matthew Osgood who neatly summed up the irritation posed by craft beer evangelists who just won’t stop it what with their knocking at the door fun, pamphlets in hand:

…my issue is that I don’t need a six-beer tasting session every time I come over to watch a game.

Jeff Alworth was exploring what things were like ten and twenty years ago in his fair town of Portland, Oregon care of a tweet and one of his best posts ever. Recent history benefits as much from reliance on records as much as the far dimmer past I wallow about in.

Rebecca Pate reported on her visit to our mutual hometown, Halifax, where she had a Pete’s Super Donair and… visited 2 Crows. Which is interesting as “crows” was a slag in my years at our mutual undergrad college.

Is Andy Crouch the first beer writer to actually pay with his own money when visiting Asheville? Seems incongruous.

And last but certainly not least remember to follow Timely Tipple for the weekly brewing history links.

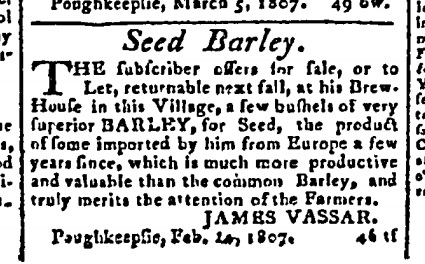

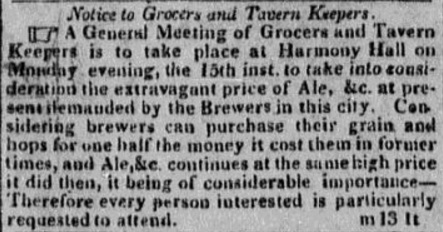

Yet, the future was now. Science was coming to agriculture in upstate New York. Ben Franklin’s

Yet, the future was now. Science was coming to agriculture in upstate New York. Ben Franklin’s