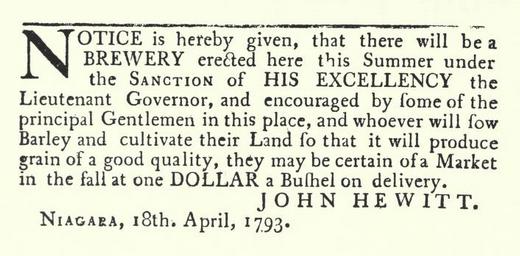

This isn’t an ad for the first brewery in Upper Canada but it is an ad for a brewery in the first edition of the Upper Canada Gazette issued the same date as stated in the ad. It is also not necessarily the first brewery in the colony but that might be a tight race. Steve Gates, sometimes comment maker around these parts, identifies Forsythe as building the Kingston Brewery in 1793, too. And, of course, it would post date the likely first brewing in what becomes Ontario by about 120 years given the Hudson’s Bay Company was packing malt in the hold on its first adventure in the 1670s. Plus, there was posssibly even commercially brewed beer in Niagara at least when the brewery was set up as the paper the first edition was printed on was from Albany NY meaning a cask or more of Albany ale may well have traveled the same journey as it had a habit of doing. It appeared on the lower right of the last page of the paper, the only ad in the whole first edition.

Category: 1700s

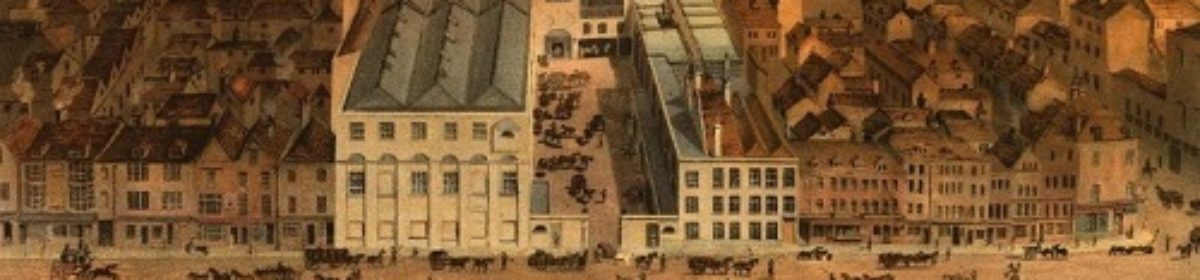

Beer Shopping: Oliver’s Beverage, Albany, New York

So, did you know I went to Albany, New York last week? It was a five hour drive down last Tuesday and another five back the next day. I enjoy the drive inordinately as it is a drive back in time south through lands settled in the early 1800s, along following the Erie Canal finished in the 1820, past pre-contact Mohawk communities, past the noses and down into the Hudson Valley first settled by the Dutch in the 1610s. And there is a great beer store. Which sorta covers two of my interests fairly well. The beer store is Oliver’s Beverages, nicknamed the Brew Crew, associated with but legally distinct from Albany Wines and Spirits presumably due to the state’s liquor laws. It’s all there in the photo above.

So, did you know I went to Albany, New York last week? It was a five hour drive down last Tuesday and another five back the next day. I enjoy the drive inordinately as it is a drive back in time south through lands settled in the early 1800s, along following the Erie Canal finished in the 1820, past pre-contact Mohawk communities, past the noses and down into the Hudson Valley first settled by the Dutch in the 1610s. And there is a great beer store. Which sorta covers two of my interests fairly well. The beer store is Oliver’s Beverages, nicknamed the Brew Crew, associated with but legally distinct from Albany Wines and Spirits presumably due to the state’s liquor laws. It’s all there in the photo above.

Craig, as master of ceremonies for the trip, took me there on Tuesday night and I went back to buy a mixed box to take home on my way out of town. This is a point to be understood clearly. It is amazingly handy for the traveling beer nerd. You pass the place if you are driving from Boston to any points west of Albany. You pass the place if you are driving from Quebec or any part west of it in Canada to New York City… or Boston. It sits near where Interstate 87meets Interstate 90 and is only, as we say, one jig and one jog from exit 5. Handy does not explain how handy this place is for the motoring beer nerd.

Second… and appreciate this coming from me… I think this is the best beer store I have ever seen. Let me explain “best”… it is massive. 1500 types of beer. I did not count. I was told. But the selection is mind boggling. And I mean this as someone whose mind in fact boggled. If you click on the two thumbnails above to the left, you will see Craig illustrating the scale of the place by first pointing to a bottle near the camera. And then running to the far end of the aisle and pointing at one there. I have a rule about US beer stores. I touch no bottle for five minutes as the whole boggling thing is to be expected. Twice this year I have read the phrase “well curated” in relation to a beer selection offered at an establishment. Screw that. I want it all. I did notice an absence of Girardin but there wasn’t much else I would miss.

The prices were also quite fair. Dupont Bon Voeux was $11.59 before the 10% mixed case discount. Ale Smith Nut Brown was $6.49. And, while it is not curated, there is curator. If you click on the thumbnail to the centre-right you will see Nico, the craft beer selection manager down at the end of another aisle. Nico, as he kept loading shelves, had all the time to chat with Craig and me on both visits, was very knowledgeable about beer nerd culture as well as his stock. I asked him about the effect of the scale of the selection and we discussed how the store was organized in such a matter that it helped the buyer cope with that. Styles and breweries are gathered within an overall geographical location, There are also shelves and shelves of ciders and perries and such.

It is in a way an artefact of this point in time. The physical space, the need to organize, the warehouse style shelving, the data all around you on signs, cards, stickers, labels and bottles. I am increasingly aware of how I am informed by space. If you look at the thumbnail to the far right up above you will see another example. It’s taken on Beaver Street just by the intersection of Green. The corner is the site of the mid-1700s King’s Arms, the 1776 flashpoint of the American Revolution in the Albany area and the founding business of the Cartwright clan of Loyalist Tories that were key to the establishment of my city of Kingston Ontario and in fact, the entire province and indeed the nation of British North Americans. But that, oddly, is not my point in posting that picture. Do you see how the street distinctly turns to the left? That turn expresses something a hundred years older than the King’s Arms, the southern design of the palisades of the original settlement. You can see it in this map from 1770 but, more particularly, you can see it in the 1695 map Craig posted to describe the community in the 1600s Dutch era. The intersection of Beaver and Green is located to the left, mid-way up. Beaver Street arcs in parallel to the settlement’s wall.

Which is interesting. Which reminds me that you can see things even when they are no longer there or, even, see things implicit in a space. Like the wall of the palisade that hasn’t been there for the best part of 300 years. Or the sound of that tavern brawl two hundred and thirty-seven which, in part, led to the creation of two countries. Or the state of good beer culture from the scale of a store.

Albany Ale: How Was 1700s Brewing Structured?

More books in the mail today. Books on colonial American economics – trade and agriculture. As Craig pointed out the other day, the last third of the 1600s and the first two thirds of the 1700s is the last bit of the story of Albany ale and associated Hudson Valley brewing that we have been looking at though he has an excellent post on the big picture. Happy, then, was I to find the following passage in 2002’s Merchants & Empire: Trading in Colonial New York by Cathy Matson:

Brewing beer, on the other hand, was a ubiquitous household undertaking and could be expanded to export production with readily available local commodities. Females throughout the countryside were probably taught at an early age how to brew for household consumption, but New York’s demand for publicly sold beer grew steadily as well. The earliest brewing houses were owned by the distillers De Foreest and Van Couvenhoven. Soon, merchant families such as the Beekmans and the Gansevoorts also brewed beer for public sale. But by the 1730s, families that ran taverns or inns owned most breweries, as in the case of Nicholas Matteysen and John Hold. Moreover, since beer was cheaper than distilled spirits, and increasingly identified with the tastes of the “lesser orders,” its production dispersed over time into the various neighbourhoods, where brewer-tavernkeepers also dealt directly with rural producers for hops, barley, and containers.

This description of production is consistent with the 1810-11 Vassar log, sibling to the mid-1830s one, that shows local farmers supplying casks, hops and grain. This makes sense as there was no great technological shift between 1700 and 1800 that should have shifted patterns of production – especially in a region still struggling with the difficult economic aftermath of the Revolution. Unfortunately, wide-spread small scale commonplace activity tends not to get recorded so we get only glimpses as in diaries from 1670 and 1749.

So, I am off to Albany tomorrow for a couple of attempts to find sources on the topic and to talk with Craig. Do they still have card catalogues? Someone must have done a study of the economics of upstate NY’s farmers between the exit of the Dutch empire and the convening of the Sons of Liberty. Surely, there is an economic argument or at least observations being made that describes the British era as not simply the prelude to independence. We’ll see.

Albany Ale: In 1670 The Best Ale Was Wheat Ale

You ever wonder why the reference you find after two and a half years took two and a half years to find? Look at this:

Their best Liquors are Fiall, Passado, and Madera Wines, the former are sweetish, the latter a palish Claret, very spritely and generous, two shillings a Bottle; their best Ale is made of Wheat Malt, brought from Sopus and Albany about threescore Miles from New-York by water; Syder twelve shillings the barrel; their quaffing liquorsare Rum-Punch and Brandy-punch, not compounded and adulterated as in England, but pure water and pure Nants.

This is a description of the drinking habits of the Dutch population of the Hudson Valley of New York from page 35 of a journal published in 1670. It was written by Daniel Denton and was called A Brief Description of New York: formerly called New Netherlands, with the places thereunto adjoining. So in addition to the 1649 legal ordinance barring brewing with wheat during a crop collapse and the 1749 reference by a traveling scientist to the malting of wheat, we have not only confirmation that wheat ale was brewed but it was the best to be had. The description by Denton is particularly trustworthy as it is incidental to other cultural references about the Dutch, particularly about their smoking and drinking habits. There is another reference to beer in his writing, too, that is quite revealing. It sits in this passage about the freedoms being enjoyed in the newish New York:

Here those which Fortune hath frowned upon in England, to deny them an inheritance amongst their brethren, or such as by their utmost labors can scarcely procure a living—I say such may procure here inheritances of lands and possessions, stock themselves with all sorts of cattle, enjoy the benefit of them whilst they live, and leave them to the benefit of their children when they die. Here you need not trouble the shambles for meat, nor bakers and brewers for beer and bread, nor run to a linen-draper for a supply, every one making their own linen and a great part of their woolen cloth for their ordinary wearing.

There you go. Freedom loving prosperous newly absorbed New Yorkers making their own wheat ale and bread from good malt grown around Albany over 100 years before the American Revolution.

So who is going to brew some up? Are there any mid-1600 Dutch guides to household management that include brewing techniques?

Pass Peter’s Pewter Pottle Pot, Please!

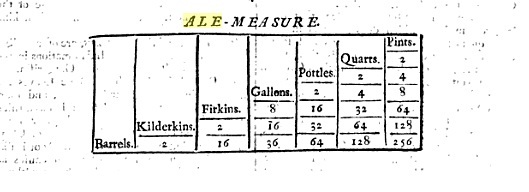

In my quest for objects out of which to drink ale, I have a 1940s ceramic part pint, an 1840s pewter quart pot and have declared 2013 the year of the 1700s etched ale glass. But, what ho! Something came before my eye today that I had not only never seen before but never had heard of – the pottle! Not an actual pottle but just the concept.

As you can see, that is archaic word for a half-gallon. The image above is a handy illustration from the entry for “Ale” in 1725’s smash best selling book Dictionaire oeconomique: or, The family dictionary. Containing the most experienced methods of improving estates and of preserving health, with many approved remedies for most distempers of the body of man, cattle and other creatures…. You will have to excuse me for deleting more than half the title but you get the hint. But now you know that there are 16 pottles to a firkin. That’s knowledge, baby.

There are a few references to pewter pottle pots on Google mainly referencing legal cases where a whole bunch of things are listed as being stolen or being in a will. In 1267, it is recorded in The Court Rolls of Ramsey, Hepmangrove, and Bury that a number of naughty brewsters of Ramsey were brought before the rather ripely named William De Wassingle – who I have no doubt was called “Assingle” behind his back – to pay fines and pledge security. Earlier in the day there was a far more interesting case which is recorded as follows:

6 d. from Emma Powel for making unclean puddings, as presented in the last view. Pledge: Simon de Elysworth. Order that henceforth she not make pudding.

You wag, Assingle. Anyway, in the brewster cases on that day, the security pledged against failure to pay the fine included many pottles. Four centuries later but still over 350 years ago, in 1659, the court heard an action of trover and conversion brought against one Gervase Maplesden by one Gabriel Beckraan for a number of things including one pewter gallon pot, one pewter quart pot, one pewter pottle pot and one pewter pint pot. Battlin’ pewterers action! Nothing like it.

But where are the pottle pots now? Not only can I find none on the internets for sale but none even pictured. Can you send an image to one of these massive drinking vessels? Have you ever seen one?

Albany Ale: Bringing Together Different Perspectives

One of my favorite things about thinking about beer is realizing that it is actually a hugely diversified discussion even if there are significant forces trying to homogenize and standardize and prioritize the discourse. The upcoming beer school at Beau’s Oktoberfest is framing this varieties of views neatly for me. Craig has been out hunting for early central NY hops and was contacted by a home brewer who has made an attempt at one possible take of Albany Ale. Ron has been discussing the early 1800s Hudson Valley brewing logs from Vassar’s brewery and connected with alumni from the college that the brewery helped found.

One of my favorite things about thinking about beer is realizing that it is actually a hugely diversified discussion even if there are significant forces trying to homogenize and standardize and prioritize the discourse. The upcoming beer school at Beau’s Oktoberfest is framing this varieties of views neatly for me. Craig has been out hunting for early central NY hops and was contacted by a home brewer who has made an attempt at one possible take of Albany Ale. Ron has been discussing the early 1800s Hudson Valley brewing logs from Vassar’s brewery and connected with alumni from the college that the brewery helped found.

Me? Me I am most interested in tracking the cultural aspects and how they fix into the context of history. I wrote Stan an email yesterday to see if he had considered the tracking of the name of CNY hops in the 1800s and had to confirm that it was not, unlike one aspect of his focus, the DNA of the varieties that I was interested in but the names given over time to the varieties. I summarized the changes and the reasons for the changes that I have been seeing in an email back this way:

♦ Post-Revolution – economic crisis that sets CNY back for best part of three decades 1775-1805. Hessian fly affects crops during this time moving beer production from wheat to hardier barley. Dutch wheat beers in Albany becomes “Bostonian” or New England style as majority of population shifts culturally. Hardscrabble farming becomes stablized farming.

♦ Post-1812 – agricultural societies, fall fairs and some scientific farming journals start. New England “improvement” moving west. Erie canal helps this take off.

♦ 1822: some sort of crisis in hop crop in UK requires reaching out for more sources, including CNY.

♦ 1830s – Robust export ale trade well underway. CNY brewers not referring to hops according to species but local supplier / grower. Exporting via ship.

♦ 1848 – UK brewers note “American hops” in their brewing log. Not by variety. [Ron has a post on this.]

♦ 1840s-60s: large and small cluster described in CNY. Geographical named hops also being referenced like “Pompey” and “Canada”. Pompey is a town. Canada is a variety that moves south, faces a false imposter and becomes “True Canada” soon after Civil War – the arse is out of all of it and mad breeding and diversification underway. Science meets money.

Keep in mind “Albany Ale” in this sense is all about the barley beer that ruled before lager takes over in around 1875 after four or so decades of expansion. Before 1775 and likely for a bit after, it remains my belief that the Dutch wheat farming of the colonial era was logically – and in accordance with the evidence – also the source of indigenous wheat beer brewing that relied on hops that were a hybrid of local wild hops and Dutch introductions. Others may have a greater interest in the industrial era when Albany was king. Or with the actual techniques of brewing. Or discovery of the actual ingredients of the beers.

Which is great. Because that is what makes the discussion complex and interesting. No one person has it right or framed the discussion.

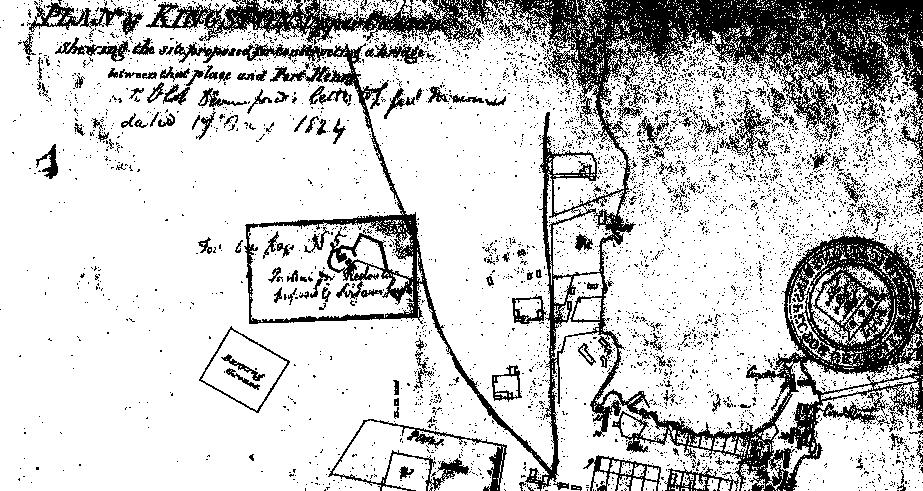

Ontario: An Early Reference To The Kingston Brewery

The funny thing about Ontario is it started as a part of Quebec. Until the division of Upper and Lower Canada in 1791, this was all the one unified colony that Britain took from France in the conquest of 1760. Settlers started moving in 1783 first from central New York in the first direct Loyalist wave, then over the rest of the decade from the eastern US seacoast as the losers of the Revolution filtered their way around up from New York, Nova Scotia and then down the St. Lawrence. An oblique reference in a land document for a Lieut. Mackay from 1794 gives an interesting hint as to the development of brewing here in Kingston, the commercial center of this new colony:

The funny thing about Ontario is it started as a part of Quebec. Until the division of Upper and Lower Canada in 1791, this was all the one unified colony that Britain took from France in the conquest of 1760. Settlers started moving in 1783 first from central New York in the first direct Loyalist wave, then over the rest of the decade from the eastern US seacoast as the losers of the Revolution filtered their way around up from New York, Nova Scotia and then down the St. Lawrence. An oblique reference in a land document for a Lieut. Mackay from 1794 gives an interesting hint as to the development of brewing here in Kingston, the commercial center of this new colony:

On May 27, 1794, a petition had been presented in Council on his behalf for “a Piece of Land about the usual Size of a Town Lot, situated on the West side of a Lot lately laid out for the Kingston Brewery, to be bounded on the North by the said Brewery on the East by a small run of Water, on the South by the Common, & on the West by the top Bank…”

The passage is from The Parish Register of Kingston Upper Canada 1785-1811, an online resource that also confirms that by 1797 it was managed by one John Darnley. That is it above shown on a map of my town from 1824. It is also shown on a map from 1865 and later additions are still there – as the 2003 photo at this post shows. There was earlier brewing in the colony but likely tied to taverns like Finkle’s in nearby Bath. Steve Gates, our comment leaver and author of the excellent book The Breweries of Kingston & The St. Lawrence Valley pegs the building of the brewery in 1793 by merchant John Forsyth but it is John’s brother Joseph who is more of the man about Kingston in the 1790s. But, as a garrison town and a depot supplying deep into the continent from the main colonial centre of Montreal, it is entirely likely that their Kingston business affairs overlapped repeatedly.

Creation of the brewery reflected some level of certainty after years of difficulty in ensuring the grain crops could supply the expanding colonial population. A 1796 letter noted in Preston’s Kingston Before The War of 1812 even speaks of the continuing infestation of Hessian Fly affecting the area. Building a brewery spoke to an expectation of peace.

Albany Ale: Did The Hessian Fly Play A Role?

It has been a bit part of the puzzle for me. As I have mentioned before, Craig as taken more of an interest in Albany Ale as reflected in the 1800s industrial period where I am more interested in the pre-1800s experience. The weird thing has been that not only do the two eras reflect issues of scale but there is that back of the brain niggling question about how, prior to a certain point right around that date, they seem to shift from using wheat malt to barley malt as the base grain. I sense Craig may be less firm than me on this. He may think I am off on a tangent. Which might be right. I think I live at the tangent most days and I trust Craig’s opinion – especially as he actually works in the world of fact at the New York State Museum where I live in the world of rhetoric as a lawyer. But I persist and, pursuing that question, ordered a copy of The Dutch American Farm by D.S. Cohen to see if I could find anything that might help me. I think I might have.

It has been a bit part of the puzzle for me. As I have mentioned before, Craig as taken more of an interest in Albany Ale as reflected in the 1800s industrial period where I am more interested in the pre-1800s experience. The weird thing has been that not only do the two eras reflect issues of scale but there is that back of the brain niggling question about how, prior to a certain point right around that date, they seem to shift from using wheat malt to barley malt as the base grain. I sense Craig may be less firm than me on this. He may think I am off on a tangent. Which might be right. I think I live at the tangent most days and I trust Craig’s opinion – especially as he actually works in the world of fact at the New York State Museum where I live in the world of rhetoric as a lawyer. But I persist and, pursuing that question, ordered a copy of The Dutch American Farm by D.S. Cohen to see if I could find anything that might help me. I think I might have.

To review, Albany is the capital of New York State. Craig lives there. One of the oldest cities in the US, it is an inland port that was settled by the Dutch in the first half of the 1600s as a fur trading centre. It sits where the Mohawk River, the eastern section of the Erie Canal, empties from west to east into the north to south running Hudson River, a couple of hours drive north of the city of New York, which itself sits at the mouth of the Hudson. As a Dutch settlement distant from other colonial settlements and, from the 1660 to the 1780, being culturally isolated from the British American experience around it, Albany took its own path for a significant period of time. Cohen states:

It is debatable, however, whether a colony in which the Dutch Reformed Church was the established church and the only religion that could be worshipped in public, in which there were large, tenanted patroonships and a company monopoly on the fur trade, and in which there was slavery, could be described as either tolerant or democratic.

As part of this singular colonial economy, Cohen describes the role wheat played in pre-1800s Albany and vicinity and includes that passage from mid-1700s traveler Swedish professor Peter Kalm that I posted earlier describing the malting of wheat as well as the volume of production. Wheat was a cash crop that was shipped south to New York city as early as 1680. Barley along with oats and rye were planted at no where near the volume of wheat. Yet wheat collapses as a Hudson Valley crop in the first half of the 1800s. In part this is due to the Hessian fly that was introduced to New York during the Revolution: “[t]he insect had apparently hitched a ride from Europe with some Hessian mercenaries employed as soldiers by the British, hence its name. First noticed in straw used at a military encampment on Long Island, the fly slowly extended its range, endangering the continent’s wheat fields for many years.”

So, there was change from pre-Revolutionary hinterland bubble of Dutch culture to post-Revolutionary national American project. And there was the transportation change from Albany as edge of Empire before the war to being just the left turn to the west after the building of the Erie Canal in the 1820s. But on top of that there was a pest that struck at wheat just as the records indicate that Albany brewers moved from making strong wheat beer in the old Dutch style to making barley based Albany Ale which was exported widely through the 1800s. Combined, all these factors explain the shift from one sort of beer to another. Which leads to the next problem of what each of them tasted like.

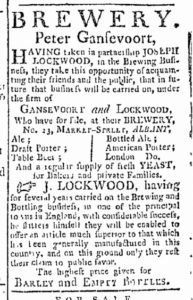

Oh, Look – Peter Gansevoort Needed Barley In 1798

After an intense amount of effort researching only the very finest digital archives, Craig (and not I) came across this sweet ad from 28 July 1798 from the Albany Gazette. He explains himself over at his blog how he was hot on the train of Edward A. Le Breton, Albany brewer in the first decade of the 1800s. This ad? Just something for me, for Al… Mr. 1600s and 1700s.

After an intense amount of effort researching only the very finest digital archives, Craig (and not I) came across this sweet ad from 28 July 1798 from the Albany Gazette. He explains himself over at his blog how he was hot on the train of Edward A. Le Breton, Albany brewer in the first decade of the 1800s. This ad? Just something for me, for Al… Mr. 1600s and 1700s.

It’s interesting how we have separated our interests generally around the time of the fall of the Federalists. The time of the Federalists’ height of power in central New York frontier is set out in Alan Taylor’s excellent William Cooper’s Town. A failed dream of an American aristocracy to replace the Loyalist aristocracy that founded my town after the American Revolution, the Federalists are about to start on their decline soon after this advertisement appears in 1798. As we learn in 1969’s breakout best seller The Gansevoorts of Albany: Dutch Patricians in the Upper Hudson Valley, Peter Gansevoort would soon demolish the brewery in 1807 after a string of partners he had hoped would take over the operation run by his family for 150 years. He was a man with a new mansion. A Revolutionary war hero who now wanted income from rents, not the troubles of actually doing things.

But what does his ad tell us. He wants barley and not wheat. Only 45 years before, touring Swedish professor noted the local – and one might speculate – traditional Dutch use of wheat malt. Through the aftermath of the Revolution, central New York is flooded with first New Englanders and then other immigrants and suffers lose of its cultural isolation. The ad also asks for empties. Which quite the thing. Bottles indicate, you know, the use of bottles. Which indicates something other than bulk communal drinking from casks, doesn’t it. For me, it is an implication of that old theme of the strength of Albany’s brew.

But most interestingly are those six sorts of drinks on offer – three porters, table beer, ale and bottled ale. Clearly predates the ad man, the marketing guru. What is it that would distinguish an American porter from a London porter in the marketplace of Albany in July 1798? Were there the great great great great great great great great great grandfathers and similarly situated great uncles of beer tickers and style nerds arguing over the difference? We know so little about the tastes of those, in the big picture, so recently alive.

Book Review: But Are These Really Beer Books?

Beer books. I have read enough of them but they are not the whole extent of the books I read related to my interest in beer. One of the most interesting things for me about my interest in beer is how is it woven though the community and through time. On top up there is my recently acquired copy of 1969’s breakout best seller The Gansevoorts of Albany: Dutch Patricians in the Upper Hudson Valley. It does appear on Google books but not much of the text is available. Below that book us the second edition of The Visual Display of Quantitative Information by Edward Tufte. I am hoping each will be, in its way, a book about beer or at least a book that explains how we can think about beer.

Beer books. I have read enough of them but they are not the whole extent of the books I read related to my interest in beer. One of the most interesting things for me about my interest in beer is how is it woven though the community and through time. On top up there is my recently acquired copy of 1969’s breakout best seller The Gansevoorts of Albany: Dutch Patricians in the Upper Hudson Valley. It does appear on Google books but not much of the text is available. Below that book us the second edition of The Visual Display of Quantitative Information by Edward Tufte. I am hoping each will be, in its way, a book about beer or at least a book that explains how we can think about beer.

First, the Gansevoorts. The most amazing thing about this family for our present purposes is that they gave up brewing in the early 1800s after the best part of two centuries of brewing… in North America. There is a lot to learn about the context of how brewing began and has continued for around 380 years in the capital city of New York state but the main thing to understand is that when the British finally took over the Dutch colony in 1674, it did not remove the population. In a way, it is like a mini-Quebec in that, through the Dongan Charterof 1686, the people of Albany were allowed a level of self-government that continued its Dutch political culture. In roads into that were only made after the French and Indian War of the later 1750s which led to the fall of New France. Interestingly, the indications I have seen of a indigenous strong Dutch wheat beer seem to fade along with that political culture replaced in the first decade of the 1800s with the ranges of small to XXXX ales more in line with the Yankees of neighbouring and expanding New England culture that lived on until swamped in turn by later German immigrants and the advent of large scale lager production. Earlier, under that cultural protection, the Gansevoorts can be traced back to the 1650s when a brewer had a daughter whose husband took up the brewing trade himself, passing the business on to their son, whose beer based position and wealth allowed his sons to prosper and lead the Revolution… and to run the brewery until it was demolished in 1807.

We have data. So much data. But it is out there in jangled family trees, in newspaper ads and in boxes on archive shelves which have remained unopened for years. How to find it all and how to put it into some order? I have an idea for an interactive timeline that effectively displays what otherwise could sit on a wiki like this. But I need help. Hence Tufte. I am thinking of his commentary on the 1869 graphically illustrated map of Napoleon’s doomed march into and out of Russia. Except it would be the Hudson River Valley and it would be about almost four centuries of of beer rather that one really poor military campaign. Something of a cross between that and the schematic diagram of the London Undergroundmight work. Maybe.

Beer books? Two wonderful books and each can tell me plenty about beer or about thinking about beer at least.