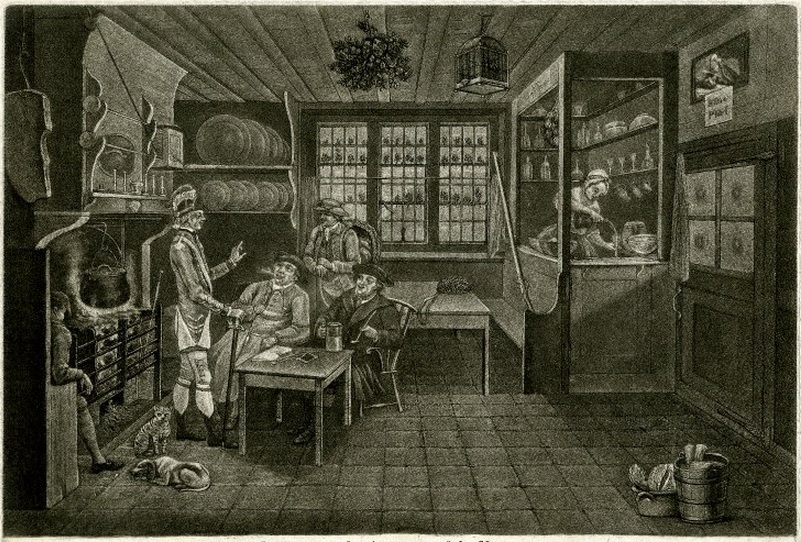

Have you even noticed I particularly like beer related stuff from before 1800. Have you noticed I like beer related stuff related to the law? Imagine then my joy when I came across a searchable database for the English Reports, the law reports series from the Magna Carta in 1215 to the Judicature Act of the 1870s… or so. The first word I put in the database was “hops” and then “hoppes” just like I did when I cam across this early modern print aggregator tool a few months back. Why hops? Something of value worth arguing over, something with a relatively clear entry point into English culture. Plunk it into the English Reports and, right off the top, three court cases pooped up from the second half of the 1700s. A perfect moment to pull out the image I tucked away for just this situation, the mid-1700s hop picking scene “Hop Pickers Outside a Cottage” by George Smith (1714 – 1776). Notice how in the image, the hop polls are brought into the yard and then are picked by hand there. It’s not without relevance.

The first case has the best narrative. In the ruling in Tyers v. Walton T. 1753. 7 Bro. P.C. 18, there is a dispute between Rev. Walton, rector of Mickleham in Surrey and vicar of Dorking, and Mr Tyers who had a certain acreage of hops within those parishes. The dispute arose because the good vicar had the right to be paid a tithe of the hops in all these two parishes. In 1745, Tyers paid the tithe in the form of 20 guineas. from 1746 to 1750, he provided a tenth of the crop after the hops were picked. 1751, however, was a bumper year and great quantities of hops grew upon the 28 acres that Tyers controlled. Tyers got greedy. He offered a maximum of 20 shillings an acre. This was refused. In response, Tyers seems to have cut the bines on every tenth hill, did not pick the hops and told the vicar to gather them himself. The law was not amused. At trial the court held that “that hops ought to be picked and gathered from the binds before they are titheable” meaning, pick ’em then divide out the 1/10th share. At the appeal hearing, the court held “the appellant had not made the least proof that the tithe of hops were ever set out before they were picked from the bind or stem.” Not the sort of thing an appellant like to hear. 1-0 vicar.

In the second case, Hunter v. Sheppard and others 1769 IV Brown 210, there is no vicar. Just a hop merchant and his purchasing agent. London-based James Hunter is described as being “one of the one of the most considerable dealers in hops in England.” His agent, named Rye, worked in the Cantebury area for years had been well known as Hunter’s man. But in 1764… there was another good year with hops bearing top price. Rye set out to make deals as an independent – without telling Hunter or anyone else. The case gets quite involved. There is much unraveling of what each landowner knew, which agent was working for which buyer and what the prices were. The Court took the matter seriously as Hunter’s purchases for that one autumn in just the Canterbury area were worth a total of 30,000 pounds. In current UK currency, that is worth £394,200,000! Money. At trial, Mr Hunter did not win the day. The judge ordered an elaborate sharing of the proceeds among a number of parties. Hunter appealed and at the appeal the Court made a wonderful observation on the nature of Hunter’s business:

The trade was at that time very particularly circumstanced, hops being in 1764, like South Sea stock in 1720, or India stock in 1767, and it required great precaution to deal in them with safety and advantage; in all which cases, the great art is to conceal the real intention; and the appellant being the most considerable dealer in England, was not obliged to let into the secret every man who pleased to speak to him on the subject, whether upon the road or elsewhere.

The panel hearing the appeal was not impressed with Hunter. One is never encouraged in court when being compared to the South Sea Bubble. The Court held Hunter sought to seriously play the Canterbury hops market and “to support these propositions he had entangled himself in a series of contradictions; and the assertions in both the answers were in many respects falsified by the evidence for the respondents.” The word fraud is then used. Too bad for you, Mr. Hunter.

In the final case, Knight v. Halsey 1797 7 T.R. 88, we find ourselves thirty years in the future but back to the question of tithes. Unlike the previous two cases, the interesting thing is not the narrative tale like something of a distant backstory employed by a Victorian novelist to establish why two families in the 1860s hate each other. The interesting thing is the recitation of the law. Knight is described as “the occupier of a certain close in the parish and rectory of Farnham” while Halsey grew hops. The dispute arose in the manner in which the hops were to be picked and divided. The Court considered the 1753 case of Tyers v. Walton discussed above but reached back farther in time to a case called Chitty v. Reeves in the Court of Exchequer, from Michaermas term 1686 brought by Ann Chitty, the widow and executrix of C. Chitty, against Reeves of the parish of Farnham. It quickly gets even better as in that case, the Court relied on even earlier evidence and held:

It fully appearing to the Court that the custom, usage, or practice of paying tithe hops in the parish of Farnham, in the county of Surrey, for above sixty years past, hath been that the impropriator or his lessee hath had for their tithe the tenth row when equal, or else the tenth hill; that the same have been left standing with the hop binds uncut, and that the impropriators, &c. have always had convenient time to come and cut the said binds the hops upon the grounds…

Fabulous. This means that in the 1797 case, the court is relying on a finding of fact based on evidence from the 1620s that people, like those in the painting above, could take their time to gather the hops owed to the church when it suited them. Boom! That is law as good clean fun. The court reviews a heck of a lot of tithe law but keeps coming back to dear widow Chitty from the time of Charles I. It also points out, conversely, that a custom which is against reason cannot prevail and is, accordingly, legally void. We gotta move on. At a time of transition into the next century’s looming industrial era, it is quite extraordinary – and Lord Kenyon, the Chief Justice admits as such when he states “[w]hether tithes be or be not a proper mode of providing for a numerous class of persons of great respectability, the clergy, I will not presume to say…” In the end, Kenyon throws up his hands at all the information before him and, I understand, orders a new trial to get to the bottom of this claim of a long standing custom versus commercial common sense.

Wow. Such drama. The good widow Chitty and the mercenary Mr. Hunter all jump out off the page, all in the name of their share of the value of the hops crop as England is balancing its rural traditional past and its modern commercial future. Neato!

This month’s edition of

This month’s edition of