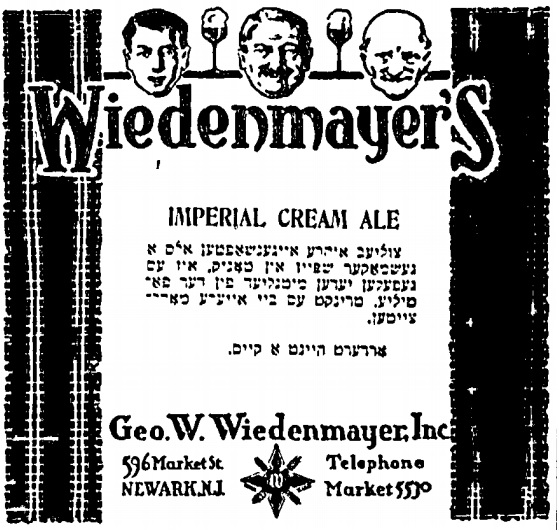

The more I get into the records referencing cream in 1800s New York brewing, the more obvious it is that the term was pervasive. It illustrates excellently, as a result, how branding existed independent of those claims to copyright we suffer from today. In law, there is an excellent and better word for such stuff that applies as much now as then – puffery. Claims made as to quality that are never ever really expected to be challenged. Look at that ad from the Jewish Daily News of 30 November 1916 again. Imperial Cream Ale. Is that the same as the Imperial Cream Ale of the Taylors of Albany from the early 1830s to the late 1860s? Or is the cream just a puff?

The more I get into the records referencing cream in 1800s New York brewing, the more obvious it is that the term was pervasive. It illustrates excellently, as a result, how branding existed independent of those claims to copyright we suffer from today. In law, there is an excellent and better word for such stuff that applies as much now as then – puffery. Claims made as to quality that are never ever really expected to be challenged. Look at that ad from the Jewish Daily News of 30 November 1916 again. Imperial Cream Ale. Is that the same as the Imperial Cream Ale of the Taylors of Albany from the early 1830s to the late 1860s? Or is the cream just a puff?

That image to the upper right? It’s a part of a column in the Plattsburg Republican from 21 August 1858 entitled “Items: or Crumbs for all kinds of

Chickens.” Is that puffery? Seems a bit more than that. Cream beer is being lumped into a class: non-intoxicating drinks. Sounds like a bit of a vague concept but at the same time the courts in New York State were struggling with the same term as it related to lager and the wider issues related to acceptance of the German immigrant wave in the middle third of the 1800s.

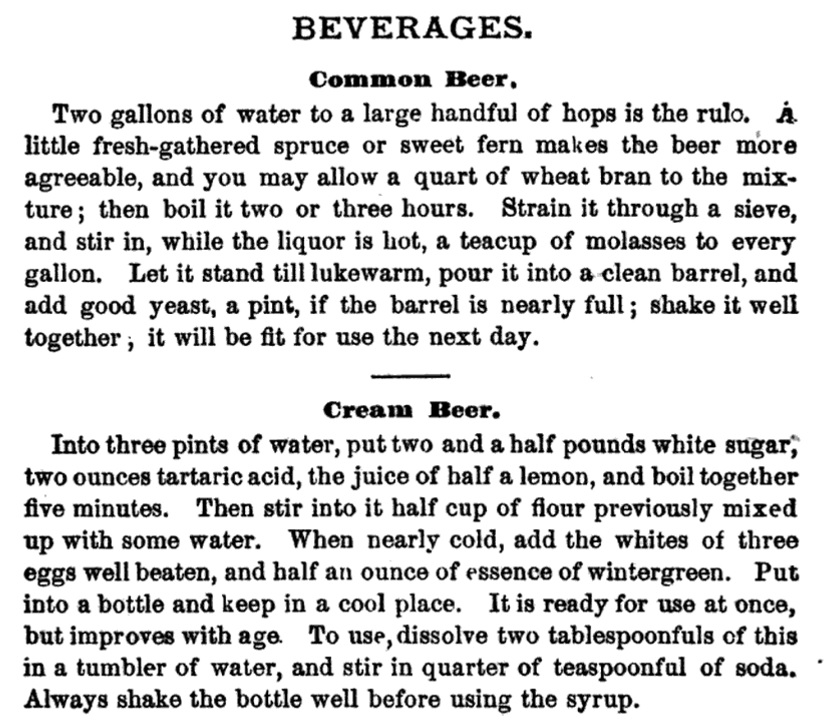

The book De Witt’s Connecticut Cook Book, and Housekeeper’s Assistant from 1871 includes these two recipes, one after the other, on page 100. The first for “common beer” has yeast added, the second, for “cream beer” doesn’t. Is “cream” then code for no alcohol? When I was a kid out east in Nova Scotia, one of my favourite things was cream soda. There were two types as I recall. Pink or clear. Pink was like drinking candy floss. Clear was like drinking candy floss… but was not pink. I hated pink cream soda. I was a clear cream soda man. Crush, if you have it… but only in Canada. Pop… soda… soda pop… was a class of soft drink that morphed out of beer. In the 1850s you could speak of California Pop Beer. In the 1830s you could speak of the Lemon Beer of Schenectady. In the excellent short book Soft Drinks – Their Origins and History by Colin Emmins, small beer is described as a progenitor of British soft drinks along with spa waters, syrupy uncarbonated cordials and that favourite of George III, plain barley water. [Continuum. Perhaps continua.] Consider the simple lemon…

The book De Witt’s Connecticut Cook Book, and Housekeeper’s Assistant from 1871 includes these two recipes, one after the other, on page 100. The first for “common beer” has yeast added, the second, for “cream beer” doesn’t. Is “cream” then code for no alcohol? When I was a kid out east in Nova Scotia, one of my favourite things was cream soda. There were two types as I recall. Pink or clear. Pink was like drinking candy floss. Clear was like drinking candy floss… but was not pink. I hated pink cream soda. I was a clear cream soda man. Crush, if you have it… but only in Canada. Pop… soda… soda pop… was a class of soft drink that morphed out of beer. In the 1850s you could speak of California Pop Beer. In the 1830s you could speak of the Lemon Beer of Schenectady. In the excellent short book Soft Drinks – Their Origins and History by Colin Emmins, small beer is described as a progenitor of British soft drinks along with spa waters, syrupy uncarbonated cordials and that favourite of George III, plain barley water. [Continuum. Perhaps continua.] Consider the simple lemon…

The earliest English reference to lemonade dates from the publication in 1663 of The Parson’s Wedding, described by a friend of Samuel Pepys as ‘an obscene, loose play’, which had been first performed some years earlier. The drink seems to have come to England from Italy via France. Such lemonade was made from freshly squeezed lemons, sweetened with sugar or honey and diluted with water to make a still soft drink.

It appears that 1660s lemonade plus small beer could be a cause of that fancy 1830s upstate NY lemon beer. Could be. There would be other intermediaries and antecedents. Think of how the sulfurous spas of Staffordshire in the late 1600s, saw the invention a drink introduced the local hard to swallow spa water into their beer brewing. Is this how it works? Isn’t that how life works?

When you consider all that, I am brought back to how looking at beer through the lens of “style” ties language to technique a bit too tightly for my comfort. The stylist might suggest that in 1860, this brewery brewed an XX ale and in 1875 that brewery brewed an XX ale so they must be some way some how the same thing. I would quibble in two ways. Fifteen years is a long time in the conceptual instability of beer and, even if the two beers were contemporaries, a key point for each brewery was differentiation. The beers would not be the same even if they were similar.

Layered upon this is the fact that “style” is an idea really fixed somewhere in the 1980s after Jackson’s original expression which was altered in the years that followed. The resulting implications are important given how one must obey chronology. This means if (i) Jackson’s 1970s “classics and cloning” idea didn’t last more than ten years until (ii) the more familiar “corner to corner classification” concept comes into being then the application of “style” to brewing prior to the 1970s (if not 1990) is also a challenging if not wonky practice. Brewers brew to contemporary conventions even though they are but points in a fluid continuum. You can’t conform to an idea that doesn’t yet exist.

All About Beer published the article “How Cream Ale Rose: The Birth of Genesee’s Signature” by Tom Acitelli on 17 August 2015 which, as we can see above, contains an origins narrative for cream ale which (though very condensed so somewhat unfair to parse) is now really not all that sustainable:

Cream ale is one of the very few beer styles born and raised in the United States. Predating Prohibition, the style grew up as a response to the pilsners flooding the market via immigrant brewers from Central Europe. Cream ales were generally made with adjuncts such as corn and rice to lighten the body of what would otherwise end up as a thicker ale; brewers also fermented and aged them at temperatures cooler than normal for ales.

I think I am good until to the word “the” in the second sentence after the comma. If style can be applied to the concept at all, cream ales at best probably represented styles. They were not a response to pilsners as they predate Gillig and were in mass production happily in their own right though the mid- and latter 1800s. They became made with “adjuncts such as corn and rice to lighten the body” but so did ales as our recreation of Amdell’s 1901 Albany XX Ale illustrated. The last sentence may well be fine.

BUT! – now notice the gem of a wee factual trail actually setting out as the specific origin of Genesee Cream Ale as related to Acitelli:

His father and grandfather, a German immigrant, had been brewers in Belleville, Illinois, about 15 miles southeast of St. Louis. Bootleggers had approached his father, in fact, about brewing during Prohibition, but he demurred. Clarence Geminn himself was completely dedicated to the craft, according to his son, a fourth-generation brewer. “Saturday and Sunday he would go into check on things,” Gary Geminn told AAB from his home in Naples, New York. “Summer picnics had to wait until the afternoon; any outing had to wait.” As for the exact formula behind his father’s most enduring beer, no one’s talking—obviously not the brewery itself, nor did the beer’s progenitor.

Mid-west Germans? Now that starts sounding more like the parallel universe of cream beer than cream ale. Does its DNA include Germans moving to Pennsylvania in the 1700s, then on inland into Kentucky in the early 1800s then into the Mid-West later that century only to back track to upstate NY by the mid-1900s? Can we draw that line? Either to connect or perhaps delineate? Maybe we need to be prepared to do both if we are seeking to understand events prior to the point of conceptual homogeneity that is achieved with the crystallization of style when MJ meets what becomes the BA.

As for cream? It’s a lovely word. So many meanings. So many useful applications. So many more leads to follow.

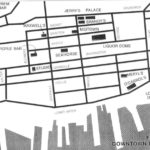

The Hall study has a number of other tidbits of information that frame the downtown scene, starting with this map. I kid myself that I could sketch this blind folded in a isolation tank but most of the locations pop back to mind immediately. The map also illustrates the general university student flow from southwest to north east, the march many evenings being from Your Father’s Mustache to the Lower Deck. And there is a concise description of what “draft” was:

The Hall study has a number of other tidbits of information that frame the downtown scene, starting with this map. I kid myself that I could sketch this blind folded in a isolation tank but most of the locations pop back to mind immediately. The map also illustrates the general university student flow from southwest to north east, the march many evenings being from Your Father’s Mustache to the Lower Deck. And there is a concise description of what “draft” was: