The Tudor resources over at British History Online are a wee bucket of gold. The last few posts under the 1500s tag are largely from the Letters and Papers, Foreign and Domestic, Henry VIII, Volume 1, 1509-1514 pages. Rather than string these last fragmentary references to beer and brewing into a likely false and certainly shallow narrative due to my lack of wider historical context, let’s just plunk them down chronologically for your consideration to see what might be made of them. Remember: rushing to any conclusion is the hallmark of disastrous pseudo-history jampacked with inauthenticity. Once I lay them out upon the table, you may feel inspired to criticize and/or praise – whether in the comments or on social media at some later date. Prehaps catch up a bit with the last few posts on the brewing plans of Henry VIII. Or just to lay upon a sofa thinking, as if you were Billy Wordsworth considering those daffodils. Feel free. Live it up.

First up, on 24 June 1509 the coronation of King Henry VIII is recorded and with it there is a list of the members of the royal household with their functions. John Knolles, yeoman “brewer” is noted under the pantry staff. Edward Atwood, yeoman “brewer” falls under the group managing the cellar. Within the buttery we find William Kerne, yeoman ale taker as well as both Thomas Cooke and William Bowman who are groom ale takers. I might suppose that these functions relate to the distribution of ale throughout the household seeing how they are located and described. Is it a case of ale at home, beer abroad? Let’s see.

In February 1512, we read of numerous royal grants of position. Grants of ecclesiastical office, grants of land to the widow of an earl. And also

Thomas Loye, brewer, of London. Protection for one year; going in the suite of Sir Gilbert Talbot, Deputy of Calais.

This is Gilbert Talbot. He traveled with his own brewer. England controlled Calais from 1346 to 1558 and Henry VIII early in his reign seems to have an great interest in ensuring it is well resourced.

On 1 October 1512, we have another record indicating the broad and integrated nature of the economy of the royal enterprise:

Account of “the victuals provided by John Shurley, cofferer of the King’s most honorable household, and John Heron, supervisor of the King’s customhouse in London, the 1st day of Oct. the 4th year of the reign of King Henry the VIII.th, for a relief of victual for the King’s army upon the sea in whaftyng (wafting) of the herring fleet upon the coast of Norfolk and Suffolk where divers of the French ships of war lay.”

Provisions with costs, viz., biscuit 72,325lbs. at 5s. the 100, and straw to lay them on, from 39 bakers named; beef, from 6 butchers in Eastcheap, 11 in St. Nicholas Fleshambles, 2 in Aldgate, total 112 pipes; beer, from 12 brewers, at 6s. 8d. the pipe (p. 11); fish “gret drye code Hisselonde fishe,” at 38s. 4d. every 124, from 2 fishmongers (p. 13); freight to 8 masters of vessels (p. 14); petty costs (p. 16); remanets (p. 19).

So, you have a navy to protect the fishermen from the French fleet and supply the fishing fleet and navy with food – including fish – to ensure the supply of fish.

Next, on 12 May 1513, The Privy Council of Henry VIII received new of a fairly particular concern related to West Country ale as preparations are made for the needs of a great army:

Since the Admiral’s coming, he has given orders, notwithstanding the King’s and Council’s commands, that no more beer is to be made in the West, as, being made of oaten malt, it will not keep so well as that made of barley malt. The soldiers are not as willing to drink it as the London beer brewed in March, which is the best month. Nevertheless, when in Brittany, they found no fault with it, but received it thankfully, and since they have been in Plymouth they have drank 25 tuns in 12 days; but now so much beer is come from London that they will not drink the country beer. My Lord of Winchester has written to the Admiral that he shall henceforth be sufficiently furnished at Portsmouth from time to time….”The quantity of victuals provided by them in the West is as follows. In Plymouth, 200 pipes of beer, 46 pipes of flesh, 20 pipes of biscuit; besides bread, biscuit, flesh and beer spent by the soldiers on land the last 12 days, for which they paid. At Dartmouth, 60 pipes of biscuit, 24 pipes of flesh, 150 pipes of beer, 300 doz. loaf bread, 200 of fish. At Exeter and Opsam, 50 pipes biscuit, 600 doz. loaf bread, 160 pipes of beer, 40 pipes flesh, 1,200 of fish.

That passage is fascinating just on the basis of the ratio of beer in the dietary demands of an army alone, but note that the news is being spread that better beer is to be had out of the recently constructed mega-brewery at Portsmouth. You also have three classes of beer described: country oaten beer from the West, City beer from London and industrial mega-brewing at Portsmouth.

Just nine days later, on 21 May 1513 the need for pipes or barrels for the beer was identified as being in short supply. Thomas Wolsey, then the chief almoner to Henry, was advised by his former master at court and soon-to-be if not now servant Richard Fox(e) as follows:

The Captain of the Isle of Wight desires Wolsey’s favor in the matter now before him. Some of my Lord Lisle’s captains desire wages for their folks that shall attend on their carriages to Calais. John Dawtrey will write the rest. Wants empty pipes for the beer. “I fear that the pursers will deserve hanging for this matter.” There shall be beer enough, if pipes may be had, “which I pray God send us with speed, and soon deliver you of your outrageous charge and labor; and else ye shall have a cold stomach, little sleep, pale visage, and a thin belly, cum rara egestione: all which, and as deaf as a stock, I had when I was in your case.”

The fear of failure was both personal and in relation to the enterprise at hand.

In June 1513, also as part of the preparations for Calais, we have this lovely specific reference to a particular person:

Wm. Antony, the King’s beer brewer. Commission for six months to provide brewers for the King’s beer brewing at Calais for the great army about to go beyond sea.

In August 1513, we see a record under the heading “The King’s Horses” of oats for horses being sidetracked to a brewer who seemed to be not exactly involved with Henry’s horses:

Account of prests (in all 25l. 4s. 8d.) and payments (in all 22l. 6s. 8d.) for hay, oats and beans sent to Calais. Some of the oats were sold to Master Alday at Sandwich, for his beerhouse.

In that same month, we also see references to the carriage of beer to Calais which indicates that the brewing there on the continent had not reached a scale allowing for local self-sufficiency. Interestingly, the beer seems to be flowing in a number of directions – (i) to ships, (ii) to Calais as well as (iii) from Calais:

“The Dockette of William Ston’s Boke,” being jottings and calculations of payments due for carriage of beer and victuals for ships including his own wages at 18d. a day for 218 days, and at 10d. a day for four days when occupied in receiving beer from Calais.

All the efforts to bolster Calais were occurring in the context of (imagine!) a war with France as I noted in the last post. As part of that larger war, Scotland did as Scotland did (oh, my people!) and decided to undertaken yet another (imagine!) suicidal adventure.* As Henry was fighting to the south, he himself at battle on the continent, Lord Howard raced to deal with an invasion of Scots and associated northern border folks. Disaster ensued for the invaders which you can read about in Howard’s report to Henry provided on 20 September 1513:

On the 9 Sept. the King of Scots was defeated and slain. Surrey, and my Lord Howard, the admiral, his son, behaved nobly. The Scots had a large army, and much ordnance, and plenty of victuals. Would not have believed that their beer was so good, had it not been tasted and viewed “by our folks to their great refreshing,” who had nothing to drink but water for three days. They were in much danger, having to climb steep hills to give battle. The wind and the ground were in favor of the Scots. 10,000 Scots are slain, and a great number of noblemen. They were so cased in armour the arrows did them no harm, and were such large and strong men, they would not fall when four or five bills struck one of them. The bills disappointed the Scots of their long spears, on which they relied. Lord Howard led the van, followed by St. Cuthbert’s banner and the men of the Bishopric. The banner men won great honor, and gained the King of Scots’ banner, which now stands beside the shrine. The King fell near his banner. (fn. 9) Their ordnance is taken. The English did not trouble themselves with prisoners, but slew and stripped King, bishop, lords, and nobles, and left them naked on the field.

“Would not have believed that their beer was so good” is perhaps the grimmest tasting note in the English language. Over 10,000 Scots died at Flodden even though they outnumbered the English. The English lost 1500.

In March 1514, once the wars to the south and north as settling or settled, we see more stability. And there is a very handy account for victualing for Calais which contains my favourite 1500s reference – malt. When they are shipping malt it means there is brewing at the destination – if not sometimes even on board the ship in transit. Meaning there is stability and perhaps peace:

John Miklowe, Thomas Byrkes, and Brian Roche. Release of 20,910l. 16s. 10d., received by them through Sir John Daunce, for purveying provisions for the army with the King beyond seas; and of 392l. 15s. received by sale of a part of the said provisions; and of various quantities (specified) of flour, wheat, casks, malt, oats, beer, flitches of bacon, &c., received by them from William Browne, junr., Richard Fermour and George Medley, merchants of the Staple of Calais, John Ricrofte and John Heron, surveyor of customs, &c., in the port of London.

Another even more detailed account including some similar names was sent the next month, April 1514:

Received of John Daunce 500l. Of Ric. Fermor, Wm. Browne and Geo. Medley, 1,000 barrels of flour at 10s.; 3,611 barrels 4 bushels 3 pecks at 8s. a barrel; 40 qrs. of wheat for brewing beer at [10]s. the qr.; empty beer barrels, 408 tons at 5s. the ton. Of John Ricroft, 7, 845 qrs. 1 bu. malt, at 5s. 4d. a qr. Of John Heron of the Custom House, London, 150 tons of beer, 150l., and 180 flitches of bacon, 13l. 10s. Received from John Daunce, for wages, by John Myklawe, Thos. Byrks and Brian Roche, 2,710l. 16s. 10d.; and by John Myklowe, and Wm. Briswoode, 3,000l. Receipt by the guaves of malt: Myklowe, Byrks and Roche charge themselves of every qr. of malt received by them “at Calais and there sold and uttered to be guaved,” 7,845 qrs. at 12d. a qr. Total received by them for victualling, wages and carriage, as appears in three books of accounts, 25,625l. 6s. 6d. Paid by them for empty foists, &c., 1,745l. 13s. 5¾d. on victuals remaining unspent, 2,235l. 11s. 8d. Losses of victuals, 2,929l. 11s. 8d. In hand, in debts, obligations and ready money, 12,574l. 3s. 4¾d. Wages of war, conduct money and jackets, for officers, artificers, carters, &c., 2,674l. 7s. 2d. For the carriage of victuals to Saint Omesr’s, 3,429l. 9s. 9¾d. Total, 25,588l. 16s. 10d. Arrearage of this account, 36l. 9s. 8d.

Interesting that the “wages of war” sometimes just meant the payment for folk and stuff to wage war with. Also, there is wheat specifically for brewing mentioned. I have not idea what “guaves of malt” are. I could not find that term listed as a unit of measurement. Seems connected to the reselling of the malt – meaning there is private brewing going on at Calais. Note also the shipment of empty beer barrels which would have, I assume, been of a specific size and perhaps durability.

On 29 May 1514, there is another reference indicating the brewing at Calais was being established at a certain scale:

Indenture witnessing delivery at Calais, 29 May 6 Hen. VIII., by John Ward to Wm. Pheleypson and Th. Granger, of 20 “myln” horses for the beer houses and 80 cart horses for the victualling of the King’s army royal.

Are “myln” horses used in the milling process?

On 12 August 1514, we have more accounting for the shipment of empty beer barrels as well as a lovely note for another necessary for beer – hops:

Giving amounts, persons by whom delivered, &c., of flour, malt, bacon, hops, bay salt, empty beer barrels and cart and mill horses. Signed: per me Thomam Byrkes.

Attentive readers, all two of you, will recall that three years ago we looked at a early modern word search tool and saw how “hops” or “hoppes” came into far more common use on a very particular date roughly around 1518. So this use of hops not only and early one in English culture but also, given this is state enterprise in the form of the industrial military complex, it is very timely… very early in the timely if you ask me. Also, goes some way to dispel the idea that Henry was against hops – he just didn’t want them in his ale.

In the miscellaneous records related to 1514, we see a few records that seem to be reconciling expenses related to the French war now that things had settled down. In particular we see records related to one John Dawtrey, only described as “a captain of the army” which must have been a more important rank than we would understand today:

Money advanced by John Dawtrey.—Payments for “land wages of the King’s army by sea”; for the army mustered before the commissioners at Portsmouth, to serve in campaign of 6 Hen. VIII.; “for wages of the army upon sea, the 6th year”; for provisions, ordinance, masts and other necessaries; for taking up a great chain; for wages of “captains, petty captains and soldiers called Swcheners when they were in the Isle of Wight,” for 5 months from 30 Dec. 4 Hen. VIII.; for fitting out The Soveraigne; for the carrack called The Gabriell Royall; for beer and bake-houses at Portsmouth; for making two gates (?) at the castles, and repairing the ditches there; and for repairing the ships.

These expenses appear to be broken out or added to in “a letter from my Lord of York to John Dawtrey.” Total: 2,100£. Or $2,369,137.42 USD today.

“Petition for sundry payments for which the accomptant has no warrant”; viz., payments for biscuits and western fish “in a great storm lost”; to Nich. Cowart, for loss in sale of wheat after the wars, and for his wages as “supervisour and having the charge of the byscuett,” and purveyor of wheat, from 24 Jan. 4 Hen. VIII. to 7 Nov. 6 Hen. VIII.; for wages of John Dawtrey and his two clerks, from 16 April 3 Hen. VIII. to 12 Sept. 6 Hen. VIII.; for carriage of money remaining in the hands of John Dawtrey from Hampton to London, &c.; for biscuits in the hands of Nich. Cowert and John Dawtrey; to Hen. Tylman of Chichester, brewer, for beer; to Rich. Gowffe of Chichester, baker, for biscuits; to _ Serle of Brighthempston, for barrels; for remainder “of wood vessels, carts, leighter and divers other necessaries,” in the charge of Rich. Palshed, at Portsmouth. “Money paid and advanced by Richard Palshed”:—for wages of brewers, millers, beer-clerks, mill-makers, coopers, surveyors, master-brewers, horse-keepers and smiths, attending upon the King’s brewhouses at Portsmouth, 5 and 6 Hen. VIII., and of certain brewers and mariners from 22 Aug. 6 Hen. VIII. to 31 March following; for expences in carriage of beer, for rent of houses, for building a great store-house at Portsmouth, for repairing the King’s garners and beer-houses at Portsmouth, for loss in sale, “after the war was done, of mill and dray-horses, wheat, malt, oats and hops; for wheat, malt, hops and beer lost and damaged at sea, and for wages of the said Rich. Palshed and his two clerks.”

Turns out Dawtrey was the Overseer of the Port of Southampton and Collector of the King’s Customs so sending him all the bills makes sense. He appears to be in charge of building and operating Henry’s four great brew houses as well as Lord Howard’s beer barrel storehouses at Portsmouth as well as paying for beer brewed by others like Henry Tylman of Chichester as well as Richard Palshed who we saw referenced as “Palshid” and “Palshide” in that brew house post. Palshed must have been the general manager brewing operations as well as likely a Member of Parliament.

Two decades on, the brewing operations at Calais are still going… sort of. In the Letters and Papers, Foreign and Domestic of the Reign of Henry VIII: Preserved in the Public Record Office, the British Museum and Elsewhere in England, Volume 9 we find the following from 27 December 1535:

Petition of Jas. Wadyngborne, of Calais, to Cromwell, chief secretary. His brewhouse at the Cawsey in the marches of Calais was destroyed in the last wars, and he then bought a house in the town standing over against the King’s Exchequer. At the King’s last being at Calais, he bought this house and others “in the said quadrant,” to the petitioner’s great loss. Bought a new house in the Middleway near the town for more than 200l., and daily brews for the town, paying excise and other charges as if he were within. ill be compelled to cease brewing in consequence of a late Act concerning the woods in the Marches, unless Cromwell obtain for him the King’s license to brew as heretofore.

There you go. Lots to chomp on. Life truly is a gas between the wars.

*See, for example, Darien.

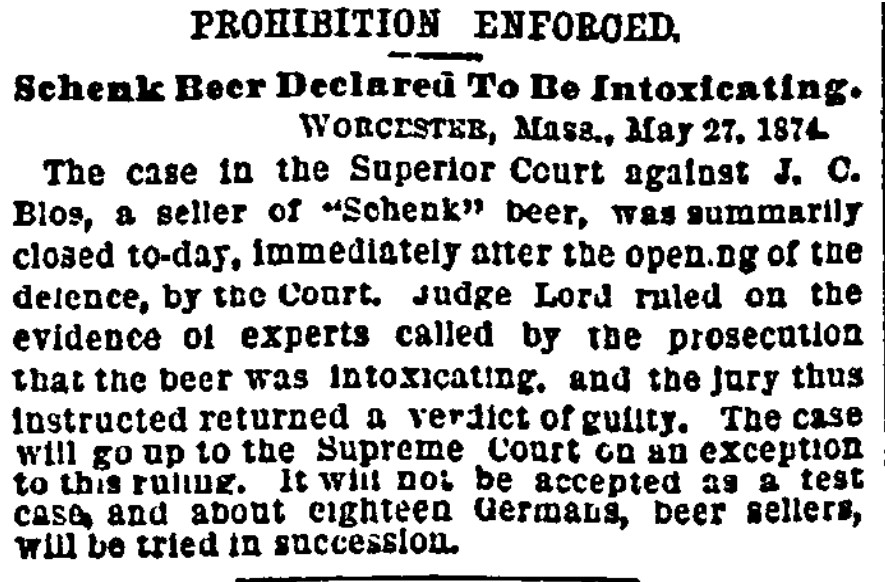

There is more background in this 2017 article and in this 2014 report in Northern New York Business magazine stated that the equipment included “vats that contained 320 barrels of beer in various stages of fermentation” so not a tiny operation. After the end of prohibition, the brewery continued for about another decade as a legitimate operation under the name Northern Brewing Co and was known for its:

There is more background in this 2017 article and in this 2014 report in Northern New York Business magazine stated that the equipment included “vats that contained 320 barrels of beer in various stages of fermentation” so not a tiny operation. After the end of prohibition, the brewery continued for about another decade as a legitimate operation under the name Northern Brewing Co and was known for its: