In 1807, a correspondent who went by the name “The Plain Dealer” wrote a letter to the editor of The Morning Chronicle on the topic of joint stock companies:

In 1807, a correspondent who went by the name “The Plain Dealer” wrote a letter to the editor of The Morning Chronicle on the topic of joint stock companies:

SINCE my last letter a number of new projects have been announced to the public, and some of them of great magnitude…. Let us begin with the Breweries. No fewer than five companies have been established, to rescue the public from bad beer at an increased price. This was a most tempting proposal. There was, after the series of unfavourable harvests, which we suffered at the beginning of the new century, an universal complaint against the beer. It was not merely lowered in quality, but composed of substitutes for hops and malt, which were thought to be pernicious; and to add to the evil, it was said to be the practice of all the great brewers, both in town and country, to buy up the leases of ale-houses, so as to deprive the publican of the freedom of going to the best brewery for his liquor. If this statement be true, it was a crying evil; but it was, and is, capable of an easy remedy. It depends entirely on the Magistrates; for if, instead of the reluctance which they now feel at the licensing of new houses, they would make it a rule, whenever a public tap was known to be the property of a brewer, and that bad beer was the consequence, to license a free house, in the immediate neighbourhood; the competition would be renewed, and the people would be served with a wholesome, palatable, and strengthening beverage. We know that the worthy Chief Magistrate of a city in the county of Kent has announced this to be his determination, and the inhabitants have already reason to be grateful to him for his device.

Competition. That was the promise of the joint stock companies. Too much wealth had gravitated into too few hands through the reactionary period after the loss of thirteen of the fifteen American colonies and then the French Revolution. The quality of beer crashed as prices climbed. But this new cure by joint stock companies was not trusted. In the string of letters to the editor in which this one is found, complaints about “sleeping partners” and “middle men” are set out. The sorts of things that people who distrust big faceless corporations floating mid-air in the stock markets still raise today. Yet there was an argument that these were tools to break the monopolies of the fantastically well connected and landed, the means to introduce competition into a status based economy. Competition was a new idea. Distrust hovered.

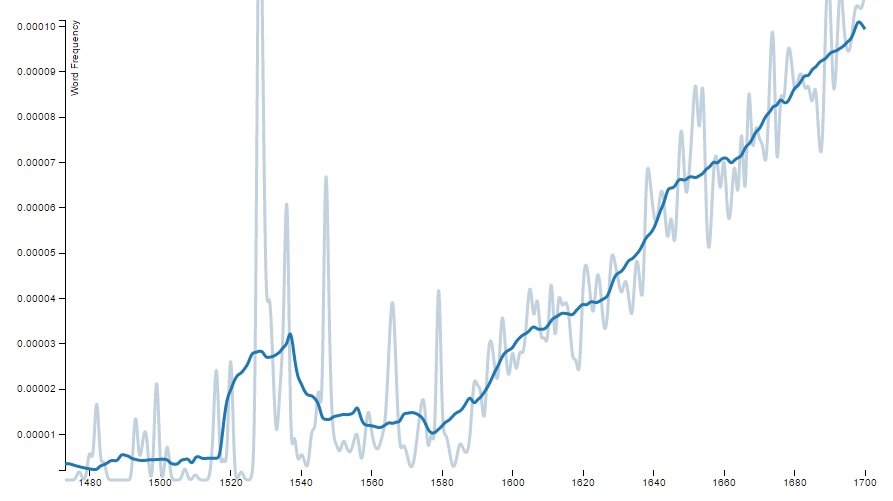

There is another reason folk were concerned other than the shock of the new. 1720. Ever since 1720, the joint stock idea was cursed. See, from the mid-1500s to 1720 there was a system of chartered companies approved and given blessing by the Crown. The most famous in Canada is the Hudson Bay Company that continues today. In our book Ontario Beer, Jordan and I describe how in the 1670s beer was being brewed in Ontario’s Arctic north by staff of the HBC over-wintering in trading posts set up to supply the firm with furs and other goods from the exotic north. A number of these were set up to encourage trade with lands as far away as Russia and Turkey… and then in the first quarter of the 1700s the South Seas. Careful readers will recall a few days ago when in the 1760 case Hunter v. Sheppard the Court described the hop buying fraudulent scheme in this way: “…trade was at that time very particularly circumstanced, hops being in 1764, like South Sea stock in 1720, or India stock in 1767…” Frauds. Bubbles. Money going in but never a hope of return coming out. The disastrous South Sea Company was the last of these companies to be chartered. And for a hundred years they remained highly suspect.

By the new century, new problems with the economy demanded a return to the concept.Unincorporated and unlisted subscription joint stock companies were forming when large groups of people subscribed into what essentially was a extremely large partnership. Described as “associations of gentlemen” they formed to break the grip of the established and wealthy in the context of the new commercial liberties and the new industrial era. One of these new enterprises was the British Ale Brewery. In an 1809 edition of The Monthly Magazine in the listings of commodity prices, one aspect of the British Ale Brewery is described: you can purchase a share in the firm for a 4 pound premium. Trading in company shares was an innovation and one that caused distrust.

But what was the British Ale Brewery? Apparently, it operated. The formation of the company was described in the 1815 court case Davies v. Hawkins:

…in 1807 a number of persons, about 600, associated together as a company, and made subscriptions, which subscriptions were divided into shares of 50 pounds each, for the purpose of establishing a brewery for ale, &c. under the name of the British Brewery. The subscribers entered into a deed which contained, among others, these provisions: that the shares should be transferable, &c. the purchaser executing the deed, and binding himself to observe the regulations, etc. contained therein; that a committee to be appointed should have power to make rules, orders, and bye-laws, subject to confirmation by a majority of the proprietors at a general meeting; that the conduct of the business of the brewery should be confided to two persons who should be styled brewers, and the trade should be carried on in their names…

The two assigned to act as brewers 1807 were Begbie and Murray. Their British Ale Brewery along with the Golden Lane Brewery were the only two breweries to complete their share subscriptions and enter trading in Britain’s early 1800s stock markets. How did it fair? In the 1808 ruling in Buck v. Buck, counsel for the firm pleaded that the intentions of the brewing enterprise were the purest:

The object of The British Ale Brewery was to carry on a lawful trade in a lawful manner, and to furnish to the public at a cheap rate, and of a good quality, an article of the first necessity It was a public benefit, therefore, instead of a nuisance, and was no more illegal than any other partnership comprehending a great many members.

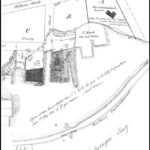

The court was not moved. It held the business to be outside the law. The brewery was supposedly located in 1810 on Church Street just south of Lambeth Palace in London between Pratt Street and Norfolk Row as shown in that 1818 map up there. Bits of those streets by those names still seem to exist near the Thames. Its twin, the Golden Lane, died off as a joint stock company in 1826. Hmm. In 1808, the same Begbie and Murray appear to take out an insurance policy for the Caledonian Brewery on Church Street in Lambeth. The equipment and the lease for the Caledonian Brewery of Lambeth are auctioned in 1824 and in 1831, one Thomas Begbie testifies before a committee on the state of the brewing trade. By 1844, the law of Britain required all joint stock companies to be incorporated and listed. Whatever happened, the brewery and the era appear to have been wound up by then.