Ron got me thinking. He was making fun of something written by Horst Dornbusch today, the “man of a million unfounded claims,” when I noticed something about pale ale coming into being around 1800 when coke was first used. I knew that was wrong so I started digging around for references to straw dried pale malts. There is something about the lack of industrialization that makes for a lack of a record of things and I thought the Coke Makers Association of The English Midlands may well have diddled the books, created history around their own inventions. And there it was… sorta… in The London and Country Brewer from 1737:

Next to the Coak-dryed Malt, the Straw-dryed is the sweetest and best tasted: This I must own is sometimes well malted, where the Barley, Wheat, Straw, Conveniences, and the Maker’s Skill are good; but as the the fire of the Straw is not so regular as the Coak, the Malt is attended with more uncertainty in its making, because it is difficult to keep it to a moderate and equal Heat, and also exposes the Malt in some degree to the Taste of the smoak.

OK, the pro-coke lobby is firmly entrenched but the quotation is from 63 years before Horst so that is worth noting. But then I notice this comment further down page 14:

The Fern-dryed Malt is also attended with a rank disagreeable Taste from the smoak of this Vegetable, with which many Quarters of Malt are dryed, as appears by the great Quantities annually cut by Malsters on our Commons, for the two prevalent Reasons of cheapness and plenty.

Interesting. Commonly used and rank. The author likes his descriptors of bad tasting: “rank disagreeable Taste” is joined by “most unnatural” and, my favorite, “ill relish.” Yet there is it – fern beer. What was fern ale like? We spend so much time hybridizing a new hop or injecting a new chili pepper extract into our beers we have forgotten the humble fern, maker of widely consumed if rank ales. In 1758’s Volume 3 of A Compleat Body of Husbandry by Thomas Hale, a bit more hope is given to the prospects for the taste of a fern ale:

The amber may be straw dried, but ’tis not nearly so well. As to wood and fern they are used in some parts of the kingdom, and custom makes the people relish the beer brewed from such malt; but to a stranger there is a most nauseous taste of smoak in it.

At least the locals liked it.

Lord Goog in the end gave up what I was looking for. In an edition of A Way to Get Wealth by Gervase Markham from 1668, a book first published in 1615 or about 200 years before the start date picked by Horst, we have an opinion on the preference for straw… and not just any straw:

…our Maltster by all means must have an especial care with what fewel she dryeth the malt; for commonly, according to that it ever receiveth and keepeth the taste, if by some especial art in the Kiln that annoyance be not taken away. To speak then of fewels in general, there are of divers kinds according to the natures of soyls,and the accommodation of places-in which men live; yet the best and most principal fewel for the Kilns, (both tor sweetness, gentle heat and perfect drying) is either good Wheat-straw, Rye-straw, Barley-straw or Oaten-straw; and of these the Wheat-straw is the best, because it is most substantial, longest lasting, makes the sharpest fire, and yields the least flame…

Look at that. We are in a different world compared to both today as well as the mid-1700s. Back to an agricultural age. “She” is the maltster. And the specific qualities amongst four classes of straw are known and ranked. After these light grain straws come fen-rushes, then straws of peas, fetches, lupins and tares. Then beans, furs, gorse, whins and small brush-wood. Then bracken, ling and broom. Then wood of all sorts. Then and only then coal, turf and peat but only of the kiln is structured to keep the smoke out of the malt.

Why? The whiz kids at Wikipedia tell us that:

In 1603, Sir Henry Platt suggested that coal might be charred in a manner analogous to the way charcoal is produced from wood. This process was not put into practice until 1642, when coke was used for roasting malt in Derbyshire.

So, coking turns out an early industrial practice that only first considered halfway through the life of Gervase Markham who lived from 1568 to 1637 and only applied to malt after his death. Coke is used to perfect – but not create – pale malts.

Pale malts and pale ales would have been around for some time well before 1600 even if in the effort to make them some became, as Markham writes at page 166, “fire-fanged.” I am sure that a fern fire-fanged ale may well have been an ill relish. But what of those whose custom made them love them all the same? Right? It’s a style just waiting to be reborn. Right? Markham would have none of it. At page 181 he states:

To speak then of Beer, although there be divers kinds of tasts and strength thereof, according to the allowance of Malt, hops, and age given unto-the fame; yet indeed there can be truly said to be but two kinds thereof, namely, Ordinary beer and March beer, all other beers being derived from them.

Got it? Fern ale is not a kind of beer, just a taste. There are two kinds of beer, ordinary and March. Everything else is showing off.

I bought this because Simon told me to. Simon said.

I bought this because Simon told me to. Simon said.

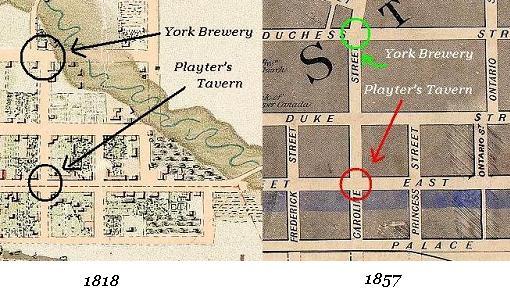

Over time Duchess is now Richmond and Caroline did become Sherbourne but that is enough to dip into the City of Toronto’s historical maps and atlases

Over time Duchess is now Richmond and Caroline did become Sherbourne but that is enough to dip into the City of Toronto’s historical maps and atlases

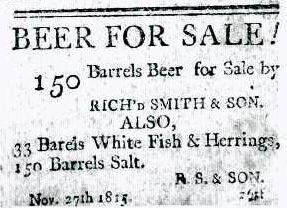

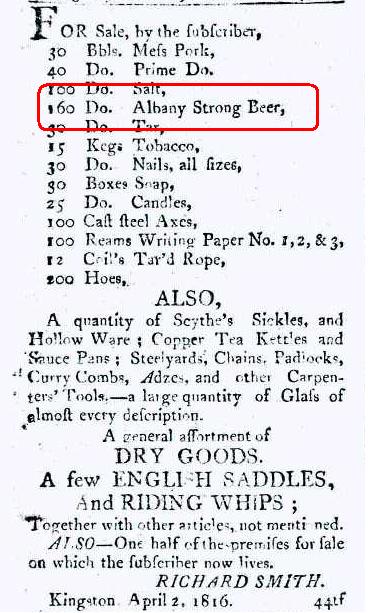

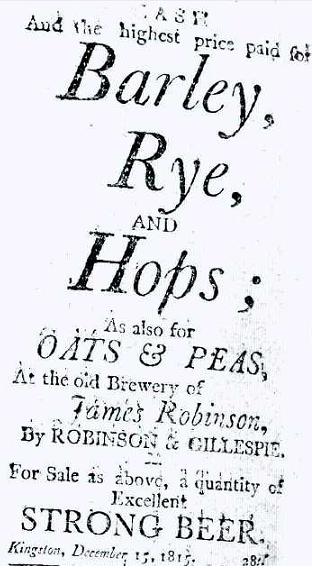

The ad is from

The ad is from