The more attentive readers will recall how back in July 2012 I wrote about the Vasser brewing book of the mid-1830s and then in November 2014 wrote about the Vassar general ledger of 1808-11. Then I wrote a whole lot about New York brewing over the last couple of years starting about here… but I never got back to the Vassars even though, due in large part to the founding of a university, it is one of the more famous 1800s pre-lager American breweries. Wonder why? Too easy? The story is pretty much out there already for all to see. Matthew Vassar is a mid-century magnate along the lines of John Taylor of Albany and perhaps even a more wealthy brewer at the time. Everybody knows that.

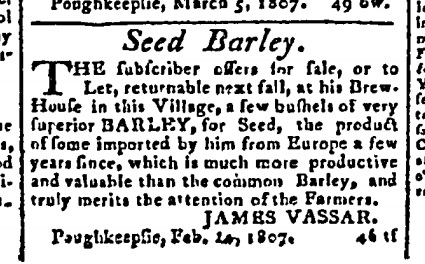

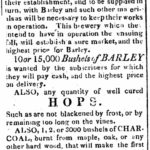

But then a notice in a paper like that one up there grabs your attention and off you go again. It’s from the Poughkeepie Barometer of 14 April 1807 and it was placed by James Vassar, the father of Matthew. See what he’s doing? He has imported a European barley strain “more productive and valuable than the common Barley” and is selling it or leasing it to his neighbouring farmers. Leasing. That is fabulous as is the fact that the leased seed is “returnable next fall”! We learned the years around the 1700s becoming the 1800s was a time of crisis and innovation in the grain zones of the youthful USA. And, as Craig has shown, six row reigned far longer as base brewing grain than was understood – just as wheat lasted far longer and was used more widely as the main brewing base before six row was accepted. So, by bringing in European barley and propagating it for a few years until he had enough to spread out to neighbouring farms, James Vassar is in his way participating in the great experiment of making America.

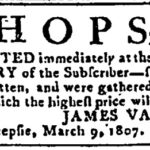

Notice that the ad way up top was placed in Feb 1807. A few weeks later, as we see to the nearer left, James posts a notice seeking hops in the same newspaper. And he wants them to be not frost bitten and “gathered last season” too. But which one could gather he was advertising for local hops. Would it be obvious that they would have to be local Hudson Valley hops? Sixteen years later, above middle, we see a notice from the New York Spectator dated 8 April 1823 that gives an update on the London hop market as of the 4th of Mark – and it is all about English hops: Kent, Sussex, Essex and even Farnham* hops all being sold from 42 to 120 shillings. I do not see, however, hop market notices from much before that point.** Hop notices appear to be more of the “I’ve got a few bales” variety like with the one to the upper right from the New York Gazette of 28 September 1821. So… my bet is that in Feb 1807, James Vassar was looking for local hops when he placed his notice in the local paper. That being the case, he is brewing local ingredients but of the best quality he can find both in terms of barley and malt.

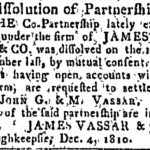

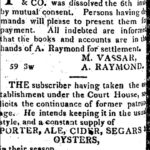

Which brings us to the 1808-1811 ledger. Vassar is making good ale branded under the name of his town. The ledger, as I mentioned in my 2014 post, places Vassar in the heart of a farming community centered on a supply town. Some of the same farmers who are growing his grain are also his customers. He also is buying hops by the pound from his neighbours, confirming my suspicions from that notice above. He is selling his beers in a town where there is a range of spirits, wine and other luxury goods from around the world according to the grocers notice next to Vassar’s November 1807 notice in the Poughkeepsie Barometer. And note something else important. The ledger runs, as you might have guessed, exactly to a point in the year 1811. This is because it is only the brewery ledger of the father, James Vassar. If you click on that thumbnail to the right you will see that the firm of James Vassar & Co. was dissolved on 15 November 1810 and accounts were settled with the partnership of John G. and M. Vassar, being the sons of James – John Guy Vassar and (“the”) Matthew Vassar.

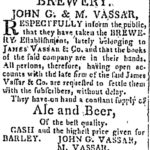

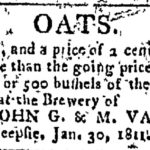

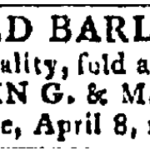

The first brewery hands off to the second. And the next generation has its own dreams. They are brewing both ale and beer and also buying barley as well as hundreds of bushels of oats according to the notice placed by the partnership in January 1811. And they are continuing in their father’s practice of selling seed barley to the local farmers according to the notice in the now fancier Poughkeepsie Political Barometer of 17 April 1811. A happy and successful succession plan has carried forward.  It doesn’t last. Weeks later in mid-May, as the article from the 15th of the month to the right explains, the brewery burns as they all seemed to burn in that era at one point or another. After the fire is controlled, however is when the real tragedy occurs. Two days later John G., the elder son of James, goes into the destroyed brewery to see how much can be saved but is overwhelmed by a gas that has settled in one of the vats and dies apparently in agony a short time later. Horrible. Sadder than even the story of Eugene O’Keefe a hundred years later.

It doesn’t last. Weeks later in mid-May, as the article from the 15th of the month to the right explains, the brewery burns as they all seemed to burn in that era at one point or another. After the fire is controlled, however is when the real tragedy occurs. Two days later John G., the elder son of James, goes into the destroyed brewery to see how much can be saved but is overwhelmed by a gas that has settled in one of the vats and dies apparently in agony a short time later. Horrible. Sadder than even the story of Eugene O’Keefe a hundred years later.

What happens then? From the notice to the left placed on 25 May, 1811 James Vassar is scrambling to call in debts from both his time running the brewery as well as the term when his sons were. then, according to the notice posted again in the Poughkeepsie Barometer on 24 July 1811, Matthew is out on his own buying up cider which might place him away from the family business at this point… or maybe diversifying. He is only nineteen years old. That Wikipedia entry says M. Vassar & Co. started up in 1814 but this add from three years earlier clearly uses that name. The next year, James is in the market seeking 10,000 bushels of Barley in September 1812. That looks like the continuation of the brewery. Which would make for the third phase. Dad. Sons. Dad.

Then what? In the 13 January 1813 paper, Matthew himself is both buying barley and selling ale and beer. Dad. Sons. Dad. Dad/Son? Then on 14 July 1813 he is entering into a brewing partnership with a Mr. Purser, rebuilding the brewery and accepting the casks of James Vassar that are still out there more than two years after the fire. And he gets into other gigs. Matthew is also running a store with a particular focus on cigars… or rather segars – but that ends up in the hands of another partner, a Mr. Raymond as you can see from the notice above to the right dated 14 July 1813, the same day the notice goes up about the new brewery. Dad. Sons. Dad. Dad/Son. Son in Partnership? Maybe. All muddling along. Moving forward.

It’s actually quite the thing that later in life he becomes a magnate given all the ins and outs of the family’s early years in the brewing trade. It starts a bit like the hapless Horsfields of Brooklyn half a century earlier but then, somehow, they spawn a genius. After the early years of the century, Matthew gets into banking and brick works, railroads and politics. But that story, the story of the rise of the great Vassar brewery, is really a separate later one.

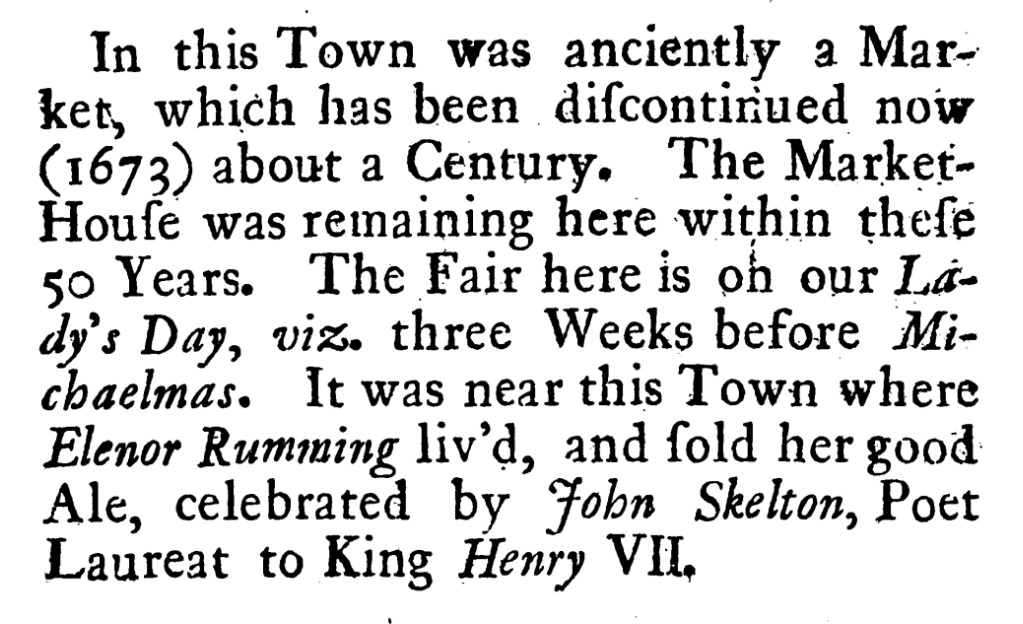

*Interesting, given the price being so much higher, that Farnham hops were discussed in New York newspapers as early as this story in the New York Journal of 20 January 1785 shows. This talk of Farnham is all for Ed, by the way.

**See also this set of New York Gazette notices from 20 February 1818 including two for hops and how geographically sourced goods are referenced expressly – Jamaica rum, Sicily Madeira, English Leather, Baltimore flour. Not the hops.

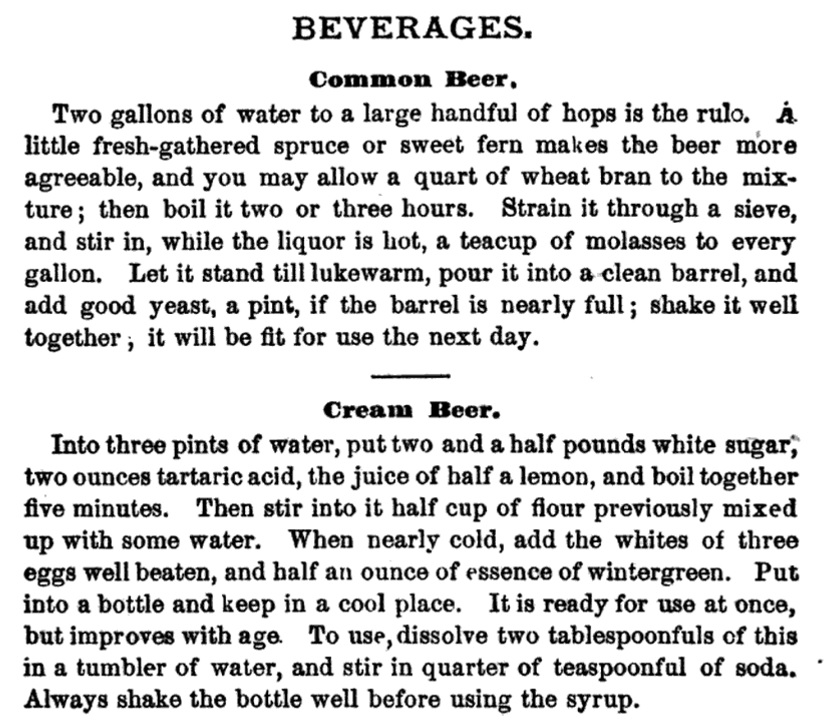

The book De Witt’s Connecticut Cook Book, and Housekeeper’s Assistant from

The book De Witt’s Connecticut Cook Book, and Housekeeper’s Assistant from

Stan responded in his flickering light bulb of a blog’s Monday links commenting “[b]ut that’s not the rabbit hole. Authenticity is the rabbit hole.” He went so far as to shout out in dispair, even in paranthetically “[i]t might be time to bring back the

Stan responded in his flickering light bulb of a blog’s Monday links commenting “[b]ut that’s not the rabbit hole. Authenticity is the rabbit hole.” He went so far as to shout out in dispair, even in paranthetically “[i]t might be time to bring back the  Jon Abernathy of

Jon Abernathy of