The further down the rabbit hole of the breweries in New York you go in the decades around the American Revolution, the further you get from great success. For many of the brewers of the 1700s that we have looked at so far – in the Hudson Valley from Long Island to Albany – brewing led to fame, military honour, riches and political power. The Rutgers and Lispenards became leading citizens to the south while generations of the Gansevoorts held sway to the north. But others weren’t as fortunate to brew for generations or to align themselves with the Revolution’s winning side. Robert Appleby was one of those. It appears. I write that caution as to the victors go the records.

The further down the rabbit hole of the breweries in New York you go in the decades around the American Revolution, the further you get from great success. For many of the brewers of the 1700s that we have looked at so far – in the Hudson Valley from Long Island to Albany – brewing led to fame, military honour, riches and political power. The Rutgers and Lispenards became leading citizens to the south while generations of the Gansevoorts held sway to the north. But others weren’t as fortunate to brew for generations or to align themselves with the Revolution’s winning side. Robert Appleby was one of those. It appears. I write that caution as to the victors go the records.

It’s not impossible to establish some understanding. That records up there? It’s a starting point. A firm one. Let me illustrate with the life of someone from the same era who I had to hunt down from outside the brewing trade as part of my work. Reference came up in a report about a James Pritchard who was one of the early Loyalist settlers of my town – Kingston, Ontario. The report I was reviewing said that not much could be found about who he was. I always figure that’s never correct and in a few hours found out a few things which made him pop into three dimensions for me. After finding reference to a tailor by that name in Philadelphia in the 1750s, he was described in a diary – the Journal of Samuel Rowland Fisher – suffering in Tory jail over a year after the British evacuation in 1778:

“11th mos: 27. Joseph Pritchard was brought into my Room, having been this day tryed at what they call the Supreme Court, for having been employed by the Brittish [sic] when in this City to attend at the Middle ferry on Schuylkill to inspect all persons going in or out of the City & was charged with having since used words greatly derogatory of the present Rulers & being by the Jury, so called, found guilty of Misprision of Treason as they term it, he was sentenced to the forfeiture of half his Lands & Tenements, Goods & Chattles, & imprisonment during the War without Bail or Mainprize . . .

11th mo: 29th. While Joseph Pritchard’s Wife was here, James Claypoole, Tom Elton, William Heysham & John McCollough broke into Joseph Pritchard’s dwelling house & took an account of all his moveables that were there; & on the day following they came again with porters and carried off almost every thing, except a Table, a few Chairs, some books & other small matters, to a house in Spruce Street, near Second Street, where they were publickly sold by Thomas Hale & Robert Smith, appointed by the present Rulers for the Sale of what they call confiscated Estates.”

Ruined by the order of the court, he was still in jail two years later. A court document from 24 October 1781 states: “The Council taking into consideration the case of the following persons now confined in the gaol of the city and county of Philadelphia, to wit: Joseph Pritchard and John Linley, convicted of misprision of treason…” He was finally pardoned and released. He makes his way to New York where he signs the New York Loyalists’ Memorial, a war-end request for reparations. Like many Loyalists, he is in a slow state of transit before appearing on a 1786-87 petition to be allowed to settle in Lower Canada – or what is now Quebec and Ontario. By 1792, he is settled in Kingston, sat as a member of a jury and, in December 1793, is a tailor suing over money he is owed. He was awarded fifteen pounds. He’s made something of the end of his life. His funeral is held in the main Anglican church in town on 10 August 1802. In the end he attains a level of stability and, in the end, there were records enough to put together a pretty good picture of a pretty loyal Loyalist. He’s a favourite Kingstonian of mine.

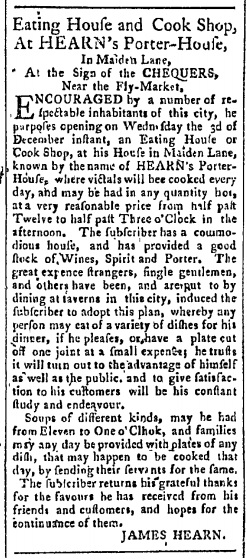

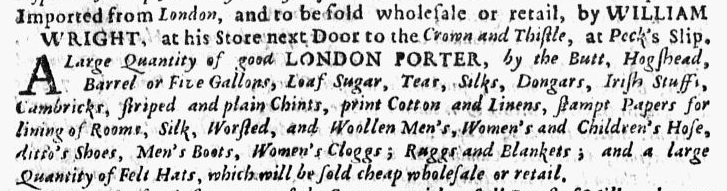

I think Robert Appleby up there has something of a parallel path to that of Pritchard but there is a little less to go on by way of records. But there is some. That notice way up top was placed in the New York Royal American Gazette of 14 April 1779. See that the brewery was recently opened and he has his first shipment of imported spruce boughs. The description of the location of the brewery sounds a bit like someone wrote it who was not local: “…at the corner of Roosevelt and Rutger Street, near the upper end of Queen Street.” He could be brewing just to survive in Tory refugee-filled Manhattan. The boughs are brought in by ship as the city is surrounded. He survives. One year later, however, he appears well settled in. Doing well. Click on the thumbnail to the left for an ad placed in the same paper on 20 April 1780. He is still selling spruce beers but has added ships beer and is even trading in London porter. He is not alone. Another spruce brewer on Staten Island is advertising in The Royal Gazette on 7 October 1780. A third notice was placed by Appleby on 1 November 1781 again in the same paper which indicates he may be moving up still further in life. It’s the middle thumbnail. A snazzier looking notice. He is now brewing with the best English malt and hops. Presumably not just with molasses as was the army’s way in the 1750s. He has also moved to Catherine Street nearer the dock yards and presumably his customers. Notice also he is bragging up his water supply. It will be “equal in quality to the Tea-Water which which the City is supplied.” All of which is good because, as you will see on the thumbnail to the right, he got married to Miss Peggy Moore on Wednesday, 8 August 1781. He did well. He is “of this city, Brewer” and she is “a very amiable young Lady of great merit.”

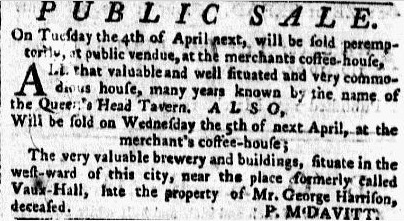

It didn’t last. Like James Pritchard who is able to live the last decade and a half of his life settled in Kingston, the Robert and Peggy (Margaret) Appleby are thrown into crisis by the Britain’s defeat and their loyalty to the Crown. They had to move on. The records of the New Brunswick Historical Society show he led a company of Loyalist refugees for Port Roseway, Nova Scotia by the ship Williams which sailed from New York on 20 September 1783. His monetary losses are valued at 600 pounds, a sizable sum. He establishes a business in his new country but it fails and, like Pritchard, he finds himself in prison. After petitioning the government – the news of which even makes the New York Morning Post of 24 January 1789 – he is released and returns to some level of status as a member of the vestry in 1788. Again, it doesn’t last. He moves back to the States, to Virginia with his wife. And, like Pritchard, he is recorded as being originally from Philadelphia.

That is a long story – actually two long stories – to make a point about records and the fate of two Philadelphia Loyalists. But notice that there is a third character, that spruce beer brewery at Catherine Street, New York, down by the ship yards. Even though I am not able to learn very much about the brewing years of Robert Appleby, we do see him start up in New York in 1779 no doubt escaping the anti-Tory movement in Philadelphia after the British capture and then retreat from the city. Then we see him relocate to a well located sweet water brewery. That brewery stays put. That brewery then starts it’s own life history. Because when the story of people can’t be traced to the level of detail in records you’d like sometimes their works can be. Let’s see who shows up.

George Appleby! Who the hell is George Appleby? Ten months after Robert leaves the town someone named George is running a very similar operation out of the Catherine Street brewery. Not his son as he just got married. His cousin? A fluke? Who knows? And he has added a treble spruce beer to his products. What the hell is that? The forerunner to Buckley’s? In 1748, there was a man named George Appleby advertising his blacksmith’s shop teasingly near Rutger’s brewery. He is named in a municipal record the next year. A George Appleby shows up on the provincial militia muster roll for what is now Brooklyn in 1755. He is 28, born in Ireland but listed as a labourer. Same guy? He’d be 21 in 1748. Could be. Only 18,000 people live in NYC in 1760 so maybe. Whoever he/they are someone by that name takes over the Catherine Street brewery in 1784 with the same last name as the former brewer. At maybe the age of 57.

And he seems to succeed. If you look at the thumbnail up there to the left, he is brewing pale ale, brown ale and table beer as well as three grades of spruce beer. I never knew the world needed three grades of spruce beer. He is also looking to hire a cooper. And notice that it’s not just George Appleby – it’s “George Appleby & Co.” It’s repeated in the middle ad from 1785. Who are the members of the company? Partnerships are the norm in brewing well into the late 1800s. Is this a real corporation that early into the independence of the USA? Before 1811 you needed a special act of the New York legislature to create an actual corporation. Puffery? Who know? In any event, if you look at the thumbnail to the right you know you can now stop worrying as by May 1788 it’s all over. The Co is no mo. Georgie boy is off with the next truck driving man he can find and takes up with him. And he moves. He and White Matlack are off to nearby Chatham Street to brew their beer there. And they seem to be movers and shakers given they are on the float along with a Lispenard representing all brewers of New York on the occasion of the 1788 constitutional parade in September of that year.They are somebodies – whoever they are. Notice another thing. They advertises in that last ad that that the new brewery is opposite the Tea-Water Pump. I thought Catherine Street had the tea water. Now it doesn’t? A wee secret. After the war, things like infrastructure break down and people flood the city. The water gets a bit crap. And much of it was brackish and disagreeable to begin with. In the mid-1780s they are already looking for good water. Remember that.

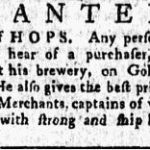

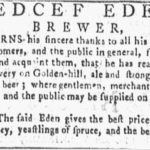

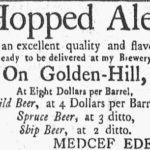

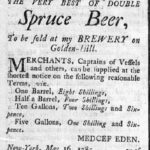

On we move. Time marches on. Keeping up? Keep up. George Appleby may be gone but the Catherine Street brewery is alive and kickin’. In the ad above to the upper left, right under the one for Appleby and Watson’s place in the New York Daily Advertiser of 10 March 1790 there is one for the new operators, Watson, Willett and Co. Their technological advance is they are brewing with real spruce essence, not off the bough. Plus table and ship beer on draught or in the bottle. Ale is gone. The two breweries seem to have a hate on for each other as they have run these ads up against each other for months. But then that doesn’t last as by five weeks later, as we see in the upper right ad, Watson and Willett and Co. gives Watson the boot after a fire with the result that the Catherine Street brewery become run by the partnership of Willett and Murray. The survivors struggle on with part of the hops and barley saved. They keep on keeping on. They seem to be in charge of the place still in 1794. As, it turns out, does George Appleby. He gave notice in the New York Daily Gazette of 21 June 1791 that he was operating out of the Golden Hill brewery of our old pal, Medcef Eden according to the lower left ad. He’d be 64 now, if he is him. The lower right ad tells the tale of how his former partner White Matlack kept the Chatham Street place by the Tea Water Pump and carried on, brewing all alone.

Have you got that straight? I need an interactive map and Gantt chart app for my mobile to keep it all straight. We will leave it there in the early 1790s for now. We’ll be picking it up. There’s a fair bit of foreshadowing in all that. A sort of an era is sort of at an end. The era of easy water? The era of the great ale brewing families? Could be. We will have to see.

Middagh Street is

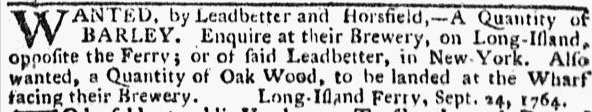

Middagh Street is  To the left you see something of the motherlode. The golden moment you dream of finding. It is the notice of the apparently unsuccessful sale of the brewery placed in the New York Mercury of

To the left you see something of the motherlode. The golden moment you dream of finding. It is the notice of the apparently unsuccessful sale of the brewery placed in the New York Mercury of

After writing my notes about

After writing my notes about

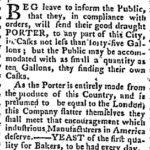

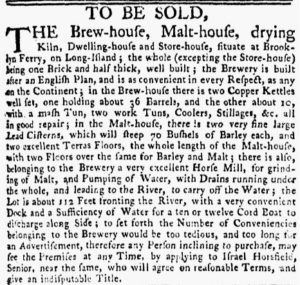

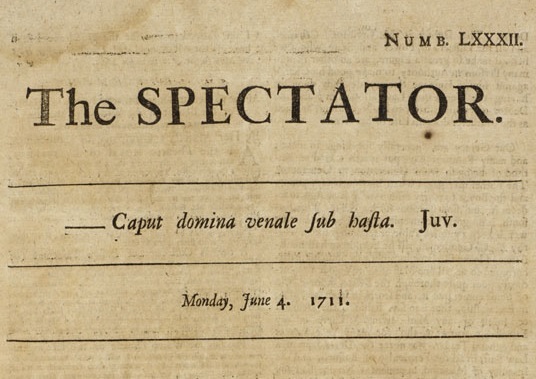

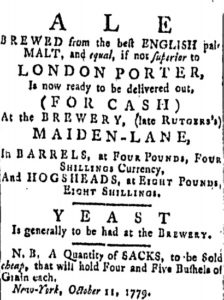

Jumping ahead, we find this ad from 1779 – the middle part of the war – which sets out some very interesting things. If you read it carefully, you will see it is not an ad for porter but an ad for a beer that is claimed to be as good as London’s porter. Imported porter is the standard to be met in the marketplace. The brewery is the

Jumping ahead, we find this ad from 1779 – the middle part of the war – which sets out some very interesting things. If you read it carefully, you will see it is not an ad for porter but an ad for a beer that is claimed to be as good as London’s porter. Imported porter is the standard to be met in the marketplace. The brewery is the