Two years ago – well, 23 months ago, I wrote a brief passing thing about the concept of “steam” beer in a post about another thing, cream ale, but given this week’s sale of Anchor, makers of steam beer who proudly proclaim they are San Francisco Craft brewers since 1896, to an evil dark star in the evil dark galaxy of international globalist beverage corporations, I thought it worth repeating and expanding slightly. Here is what I wrote:

Adjectives from another time. How irritating. I mentioned this the other day somewhere folk were discussing steam beer. One theory of the meaning is it’s a reference to the vapor from opening the bottle. Another says something else. Me, I think it’s the trendy word of the year of some point in the latter half of the 1800s. Don’t believe me? Just as there were steam trains and steamships, there were steam publishers. In 1870 there was a steam printer in New Bedford, Massachusetts. A steam printer was progress. Steam for a while there just meant “technologically advanced” or “the latest thing” in the Gilded Age. So steam beer is just neato beer. At a point in time. In a place. And the name stuck. That’s my theory.

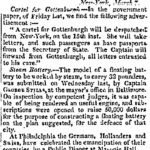

And here is what I would like to add. To the right is a news item from the Albany Gazette of 10 March 1814. As I have looked around records from the 18o0s for example of the use of “steam” I describe above, I found this one describing a steam battery both early and entertaining. I assumed on first glance that this was some sort of power storage system. In fact it is for a barge loaded with cannon. 32 pounder cannon which are rather large cannon indeed. Well, all cannon are large if they are pointed at you I suppose but in this case they are significant. For the nationalist vexiologists amongst you, I can confirm that the proposed autonomously propelled barge system of cannon delivery was reported six months before the Battle of Baltimore. Were they part of the sea fencibles? Suffice it to say, as with steam publishing and steam train engines you had steam based warfare by battle barge.

And here is what I would like to add. To the right is a news item from the Albany Gazette of 10 March 1814. As I have looked around records from the 18o0s for example of the use of “steam” I describe above, I found this one describing a steam battery both early and entertaining. I assumed on first glance that this was some sort of power storage system. In fact it is for a barge loaded with cannon. 32 pounder cannon which are rather large cannon indeed. Well, all cannon are large if they are pointed at you I suppose but in this case they are significant. For the nationalist vexiologists amongst you, I can confirm that the proposed autonomously propelled barge system of cannon delivery was reported six months before the Battle of Baltimore. Were they part of the sea fencibles? Suffice it to say, as with steam publishing and steam train engines you had steam based warfare by battle barge.

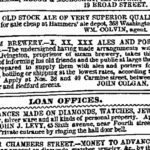

Next – and again to the right – is a notice placed in the New York Herald on 11 September 1859 indicating that John Colgan was selling three grades of ale and perhaps three grades of porter after “having made arrangements with W.A. Livingston, proprietor of steam brewery…” This appears to be an example of contract brewing where Livingston owns the brewery and contract brews for the beer vendor, Colgan. Aside from that, it is a steam brewery. Livingston’s operation was listed in the 1860 Trow’s New York City Directory along with a number of other familiar great regional names in brewing such as Vassar, Taylor and Ballantine. And it lists over two pages a total of four steam breweries, including Livingston’s. Which makes it a common form of industry marketing.

Next – and again to the right – is a notice placed in the New York Herald on 11 September 1859 indicating that John Colgan was selling three grades of ale and perhaps three grades of porter after “having made arrangements with W.A. Livingston, proprietor of steam brewery…” This appears to be an example of contract brewing where Livingston owns the brewery and contract brews for the beer vendor, Colgan. Aside from that, it is a steam brewery. Livingston’s operation was listed in the 1860 Trow’s New York City Directory along with a number of other familiar great regional names in brewing such as Vassar, Taylor and Ballantine. And it lists over two pages a total of four steam breweries, including Livingston’s. Which makes it a common form of industry marketing.

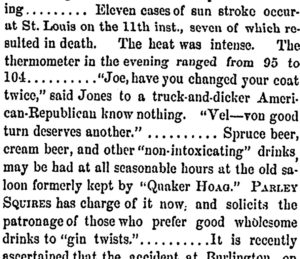

“Steam” is quite venerable as a descriptor of technology. If you squint very closely at this full page of the Albany Register from 29 January 1798 you will see steam-jacks for sale. It is also a term that moved internationally. In the New York Herald for 15 September 1882, you see two German breweries named as steam breweries. And again in the Herald, in the 10 August 1880 edition to the right, we see the sale of the weiss brewery at 48 Ludlow Street details of which included a “steam Beer Kettle” amongst other things. One last one. An odd one. If you look at this notice from the Herald from 14 June 1894 you will see a help wanted ad seeking a “young man to bottle and steam beer.” Curious.

“Steam” is quite venerable as a descriptor of technology. If you squint very closely at this full page of the Albany Register from 29 January 1798 you will see steam-jacks for sale. It is also a term that moved internationally. In the New York Herald for 15 September 1882, you see two German breweries named as steam breweries. And again in the Herald, in the 10 August 1880 edition to the right, we see the sale of the weiss brewery at 48 Ludlow Street details of which included a “steam Beer Kettle” amongst other things. One last one. An odd one. If you look at this notice from the Herald from 14 June 1894 you will see a help wanted ad seeking a “young man to bottle and steam beer.” Curious.

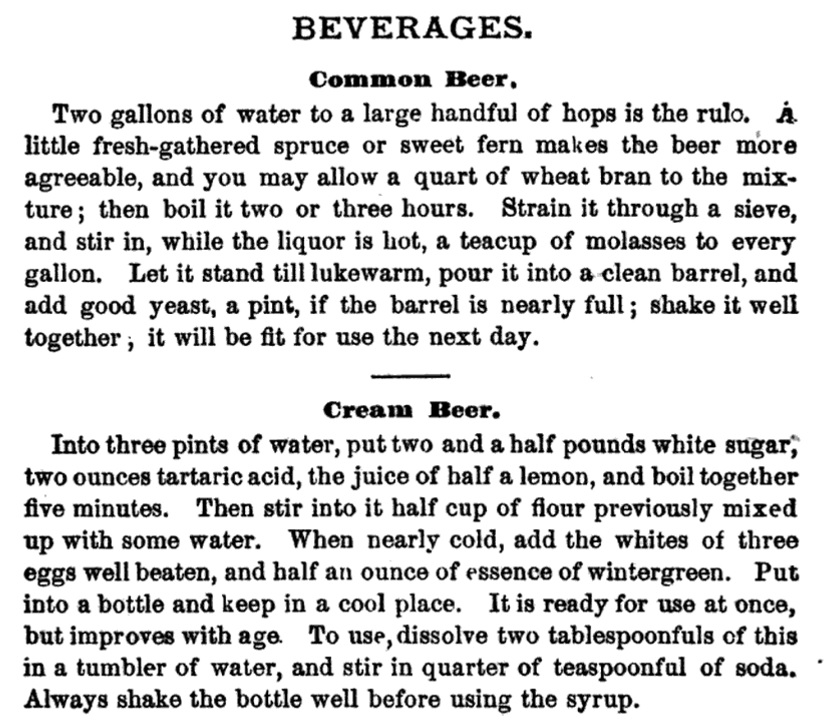

What does any of it mean? Well, steam beer and common might have a lot more to do with each other than the just the name of a style.

The book De Witt’s Connecticut Cook Book, and Housekeeper’s Assistant from

The book De Witt’s Connecticut Cook Book, and Housekeeper’s Assistant from