Building on part one of this struggle, let’s consider the passage above again for a minute. It is from volume 7 of The Reliquary, by John Russell Smith, 1867. It looks a lot like the passage by Mott from 1965 that I quoted (poaching as I noted from the Martyn of 2009) in my previous part of this consideration of 1600s Derby ale. If we unpack it we see a number of things at the outset: small scale decentralize industry, great fame… and two products. Both ale and malt. But what made Derby ale… Derby ale? Let’s start from the last bit.

i. Two Commodities

Both ale and malt. It’s a common theme. In Magna Britannia: Volume 5, Derbyshire by Cadell and Davies published in 1817 we find another similar statement like the one made by J.R. Smith above:

The chief trade of Derby, about a century ago, consisted in malting and brewing ale, which was in great request, and sent in considerable quantities to London; in corn dealing also, and baking of bread for the supply of the northern parts of the county

And again, in The History of the County of Derby by Glover from 1829 is is stated:

About two centuries ago, according to Camden, the chief trade consisted in malting and brewing ale; which he spake of as being in great request, and much celebrated in London, to which city large quantities were sent.

Camden is William Camden who, conveniently for our purposes, dies in 1623 after writing a survey of Britain but well before coke. In his chapter of “Darbyshire”* in the late 1500s Camden wrote:

…all the name and credit that it hath ariseth of the Assises there kept for the whole shire, and by the best nappie ale that is brewed there, a drink so called of the Danish word “oela” somewhat wrested, and not of alica, as Ruellius deriveth it. The Britans termed it by an old word “kwrw” , in steede whereof curmi is read amisse in Dioscorides, where hee saith that the Hiberi (perchance he would have said Hiberni , that is, The Irishmen ) in lieu of wine use curmi , a kind of drinke made of Barly. For this is that Barly-wine of ours which Julian the Emperor, that Apostata , calleth merrily in an Epigramme πυρογενῆ μᾶλλον καὶ βρόμον, οὐ Βρόμιον. This is the ancient and peculiar drinke of the Englishmen and Britans, yea and the same very wholsome, howsoever Henrie of Aurenches the Norman, Arch-poet to King Henrie Third, did in his pleasant wit merrily jest upon it in these verses:

Of this strange drinke, so like to Stygian Lake

(Most tearme it Ale), I wote not what to make.

Folke drinke it thicke, and pisse it passing thin:

Much dregges therefore must needs remain within.

The next paragraph is even more interesting:

Howbeit, Turnebus that most learned Frenchman maketh no doubt but that men using to drinke heereof, if they could avoid surfetting, would live longer than those that drinke wine, and that from hence it is that many of us drinking Ale live an hundred yeeres. And yet Asclepiades in Plutarch ascribeth this long life to the coldnesse of the aire, which keepeth in and preserveth the naturall heat of bodies, when he made report that the Britans lived untill they were an hundred and twenty yeeres old. But the wealth of this towne consisteth much of buying of corne and selling it againe to the mountaines, for all the inhabitants be as it were a kind of hucksters or badgers [salesmen].

Dealers. In grain. Fabulous. Brewers of beer and dealers in grain. Look at that passage from Mott (quoted in part one) again:

Much malt was carried to the ferry on the river Trent, five miles away, whence it could go by water to London; 300 pack-horse loads (each of 6 bushels which each contained 40lb) or 32 tons were taken weekly into Lancashire and Cheshire.”

The trade in malt is not the trade in ale and it’s not the trade in barley. We see the malt from Derbyshire referenced as late as in the mid-1700s. Pamela Sambrook in her 1996 book Country House Brewing in England, 1500-1900 wrote:

Particularly prized among midland brews houses in the early eighteenth century was ‘Darby’ malt. It is mentioned repeatedly by William Anson in his notebooks as the basis of the best-quality strong brews at Shugborough. Derby malt was also used by the Jervis household near Stone and the Farington household of Worden in Lancashire in the 1740s.

The export of Derby malt also pre-dated the generally accepted 1640s application of invention of coke to the malting process. And it was worth taking a risk over. Dorothy Bentley Smith in Past Times of Macclesfield, Volume 3 describes the laying of malt related charges:

On December 1629, James Pickford (former Mayor of Macclesfield 1626/27) a tanner by trade of Pickford Hall on Parsonage (Park) Green together with tow accomplices, George Johnson and Roger Toft, appeared in Court in Chester. Their crime: They had erected a handmill or quern in Wildboarclouggh to the detriment of the three Macclesfield mills. Pickford had family connections in Derby and admitted supplying the inhabitants of Macclesfield with Derby malt “as others had done” Malting was the principle trade in Derby, from here supplies were sent to the greater part of Cheshire, Straffordshire and Lancashire, with a considerable portion taken to London by which many good estates have been raised” (a comment written by a historian, Mr Woolley, in 1712).

So, it’s pretty clear that well before coke, Derby malt was a thing and a desired thing. Moved by massive pack horse trains, by water as discussed in the first post or by subterfuge as the Pickfords of Macclesfield illustrate. Folks wanted their hands on it.

ii. Top quality selected barley

What made Derby malt so popular? Was there a singular characteristic like the particularly sulfurous waters in Staffordshire where in the 1680s a satantic ale was brewed at the Brimstone Alehouse that later may well have been tamed to become the hallmark of Burton ale a quarter century later?

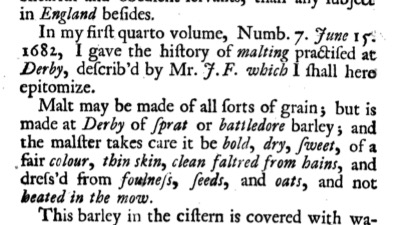

Just as the function of pre-coke straw kilning played a role as discussed in the previous episode of this head scratching tale, so too was the sort of barley being malted important. Houghton in his book on husbandry recites a reference from one of his earlier writing’s from 1682, as you can see above. Note that states that it is made of “sprat or battledore” barley. Careful readers will recall that Battledore was one of the identified varieties of barley in the 1700s.** It was also known as Spratt or Sprat and as such was a parent to that darling of English brewing before mid-1900s Maris Otter, Spratt-Archer. And it was in a way, selected and treated as an improved variety well before Chevalier was introduced in 1823. Consider this passage from The Modern Husbandman, Vol II at page 9 and 10 written by William Ellis from 1750 where Battledore is described by another of its common names – Fulham barley:

…the Hertfordshire Farmers, several several of them, send for Fulham Barley-seed above thirty Miles an End, and all by Land carriage. Now, though we have sandy, chalky, and gravelly Lands just by Home, yet, we at Little-Gaddesden chuse to be at the extraordinary Charge of sending for this Fulham Barley-seed, though we live Thirty-four Miles from it, and find our Account in so doing for as we sow it in our stiff Loams, from off a fandy short Loam, it returns us a very early Crop, with a Kernel much bigger than that we sowed, and is so natural for making true Malt, that it is commonly sold for two Shillings a Quarter more than our common Barley…

Ellis goes on to list other reasons for “Fulham Barley seed before all others.” You can grow a turnip crop or rape-seed or wheat in a cycle with it. it is so early, it gets a good air drying. It has a shorter season making it useful in northern plantings. It is also available as seed grain by water transportation. Plus we know it made excellent straw which mean not only could it withstand a storm but it provided one means, other than sun drying, before coke to make pale malt by flash kilning the barley with clean fuel. So, the use of Battledore – by one of its many names – was the use of the choicest barley known to the England of the 1600s.

iii. Growing and Integrated but Decentralized Barley Production

And it was not just the quality of the barley. It was the quantity of the quality. Access to lots of top quality barley was also important. You are not building a pre-industrial hive of… industry without a fair bit of the raw resources. In volume 16 of the Derbyshire Miscellany, there is a wonderful study of the inventories and wills of farmers in the parish of Barrow-upon-Tweed to the south of Derby. What it describes are many farms growing barley at the time in question. At page 24 there is a very helpful table that shows how from the early 1500s to the late 1600s the percentage of farmers growing barley rose from 18% to 45%. Interestingly, mention is made of not only barley but big barley as a distinct crop sometimes stored separately. The sophistication in separating and blending grains is evident. Farmers also store malt and some even have separate well appointed brew houses. In Elizabethan Barrow-upon-Trent one farmer posessed eight steepfatts, aka steeping vats or mash tuns.

But local barley feeding in to the Derbyshire machine was not enough. In 2016’s Farmers, Consumers, Innovators by Dyer and Jones, there is a description of how the demand for Derby malt was so great that barley was brought in from neighbouring districts. They state that similar probate inventories indicated that large quantities of barley were being grown in neighbouring Nottinghamshire and that Derby maltsters depended on it and other sources:

…it seems that the inhabitants of Derbyshore were keen to make up any shortfall they might have had in the barley output of their own county by buying in barley and malt from elsewhere. Derby was famed as a centre for malting; according to Camden its trade was “to buy corn [grain], and having turned it into malt, to sell it again to the highland counties.”

Which tells us a few additional things. At a time when many grains were grown and stored both separately and blended in mixes, Derby malt was focused on barley and, as seen above, top quality barley. And then it was made into a regional trade named product, aggregated in the storage barns by the river described in part one or by the 300 weekly loads by pack-cart and sold on to markets. The aggregation of the trade is similar to the one in hops we saw in the mid-1700s court ruling discussed two and a half years ago where the purchasing agent went rogue on his boss, the hop dealer:

London-based James Hunter is described as being “one of the one of the most considerable dealers in hops in England.” His agent, named Rye, worked in the Cantebury area for years had been well known as Hunter’s man. But in 1764… there was another good year with hops bearing top price. Rye set out to make deals as an independent – without telling Hunter or anyone else.

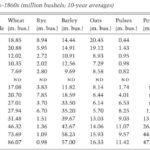

So, the many maltsters in derby 1690 Houghton were a part of the same sort of supply chain well before control of all stages in an industrial output was considered. The key spot in that chain which Derby places itself is important, too.  Malt was by far a premium priced bulk product over unmalted barley. William Ellis above noted in the mid-1700s that malt was worth two shillings more a quarter compared to barley. And as Broadberry, Campbell, Klein, Overton and van Leeuwen show in their 2015 text British Economic Growth, 1270–1870 (as summarized in the remarkable and remarkably clickable table to the right) that premium coincided with a general jump in barley production in the 1600s:

Malt was by far a premium priced bulk product over unmalted barley. William Ellis above noted in the mid-1700s that malt was worth two shillings more a quarter compared to barley. And as Broadberry, Campbell, Klein, Overton and van Leeuwen show in their 2015 text British Economic Growth, 1270–1870 (as summarized in the remarkable and remarkably clickable table to the right) that premium coincided with a general jump in barley production in the 1600s:

The output of barley increased markedly in line with demand for better-quality ale and beer brewed from the best barley malt.

So, the folk of Derby build the name for their malt and sell it to the country just as ale quality is peaking in general demand.

iv. Speculative Conclusion

All of which leads me to a question. As Jordan and I saw in our research that went into our cult classic history Ontario Beer, the cost of transportation was a great issue in the colonial boom of 1800s before 1867 and national Confederation. Beer was heavy and the roads were poor. Which meant whisky was carted inland and beer was for the lakeside towns. Above, we see that discussion by William Ellis on around 1750 describing the extraordinary costs being paid to move Fulham barley seed just thirty-odd miles. Yet, Derby malt is shipped out by pack horse and cart from county to county and Derby ale is prized in London. Why is it worth it?

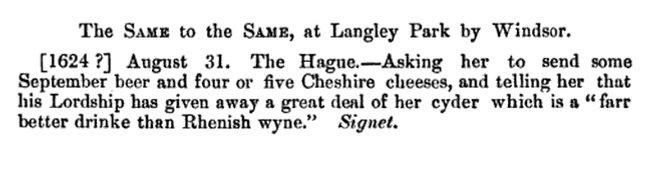

What if Derby malt was so singular that ale made with it anywhere carried the mark? What if the malt was thicker, stronger, paler and so clear of smoke that even a London brewer could make identifiable Derby ale that matched what was brewed in its home county and stood above the competition? Was that what Pepys was drinking? I don’t know. So I will leave it there for now to see if I can find more about the shipment of malt into London from Derbyshire in the 1600s. I need to learn more about who was receiving what was being shipped out of the county.

*Note again the plague that is foisted upon the pure hearted digital document scanning historian.

**Pete B in his Miracle Brew suggests at page 30 that barley prior to the cultivation of Chevallier in 1823 was simply a landrace. Use of “landrace” as it comes to hops, say, in NY State in the early 1800s can be code for “an inability to go back farther in records” sometimes unfortunately laced with a dash of “I could not be bothered looking for more information.” My inclination was to consider this not correct as this 1790s discussion – let alone Houghton in 1682 – confirms. There were clearly species of barley known and made subject to husbandry before 1832 in England. But then consider this: “[a] landrace represents the equilibrium… within… a crop… under a given set of climactic, soil and husbandry conditions.” That seems to be what Battledore was… yet it was also selected and traded. Conversely, the same text Diversity in Barley discusses “barley breeding” as “conspicuously… different plants within local landrace populations together with separate harvest and seed multiplication.” So, landrace triggers breeding. Which makes landrace not a simple thing at all.