It should be no secret that I have looked forward to the publication of 20th Century Pub by Boak and Bailey ever since the project was hinted at on their blog. The feeling reminded me of the release some years ago of Pete Brown’s Hops And Glory which I reviewed over four blog posts in 2009. What I think I find most similar between my expectations for these two books is the anticipation of work by authors who have proven themselves to be creative and committed in their previous books. I am only half way through 20th Century Pub but it has already exceeded even these expectations – so much so that I want to jump queue to tell you about their methodology and why I think you should just to email them and buy this excellent bit of work.

This book reminds me a bit more of their neither long nor short work, 2014’s Gambrinus Waltz: German Lager Beer in Victorian and Edwardian London than their perhaps more well known first book, later that same year’s Brew Britannia. I say that because the historical narrative is driven a bit more by the greater context of society than just the players involved. One of the odd things about the history of micro brewing and later craft beer is how personality drives the discussion. That is fine for early days when there were a few people (although sometimes not necessarily the same few people, the successful survivors, who self-identify) who were the actual pioneers. And, to be fair to those involved, the early days of craft appear to not have generated as many records considered worth retaining as we keeners today might have wished.* However, while it is fun to learn about these people and (as sometimes occurs) associated vicariously with them, it is far more interesting to understand how brewing and beer and pubs and taverns actual existed and exist in the greater context of society based on records which were created contemporaneously. For larger events it is best to seek out authority elsewhere.

This book reminds me a bit more of their neither long nor short work, 2014’s Gambrinus Waltz: German Lager Beer in Victorian and Edwardian London than their perhaps more well known first book, later that same year’s Brew Britannia. I say that because the historical narrative is driven a bit more by the greater context of society than just the players involved. One of the odd things about the history of micro brewing and later craft beer is how personality drives the discussion. That is fine for early days when there were a few people (although sometimes not necessarily the same few people, the successful survivors, who self-identify) who were the actual pioneers. And, to be fair to those involved, the early days of craft appear to not have generated as many records considered worth retaining as we keeners today might have wished.* However, while it is fun to learn about these people and (as sometimes occurs) associated vicariously with them, it is far more interesting to understand how brewing and beer and pubs and taverns actual existed and exist in the greater context of society based on records which were created contemporaneously. For larger events it is best to seek out authority elsewhere.

Thankfully, their tale of micro brewing and craft’s origins in the UK, Brew Britannia, did just that and relies on primary documents from the time in addition to interviews of persons involved looking back from three decades later. This book repeats that process and explores the subject matter from the wider range of sources. This is detailed and time consuming work – and the work undertaken shows in the result set out on these pages. An example. I have just read the chapter on 1950s estate pubs. To understand what an estate pub is you need to understand estates and to understand estates you need to understand British municipal planning principles of the first two-thirds of the 1900s.

I am somewhat familiar with this. I am a municipal lawyer. And some of you may have picked up that I am a dual national, Canadian and British. Many of my UK family when I was young lived in what we here in Canada would call “public housing” but in the UK the word for much of it was “estate” and they look at lot like what we might consider a condensed post-WWII subdivision when it wasn’t a low rise apartment building. My grannie, aka Bailee M’Leod aka Dad’s mother, as a municipal Labour politician was actually involved actively in the 1930s to 1950s in destroying slum neighbourhoods of the 1840s and building these sorts of forms of public housing. These events fed my bedtime stories, tales of the old country when they were not about Nazi bombings of the Clyde.**

Knowing that bit of the background, I am able to trust the point being made. Placing the particular point in its context is one of the great successes of this book. Boak and Bailey weave the the meaning of estate as they explain the estate pub, a somewhat sterile slightly spare Scandinavian set up that were allocated strategically through these new living spaces by municipal planning processes. Likewise, earlier in the book they contextualize the end of the Victorian gin palace and how it was responded to by the State Management Scheme of pubs introduced after WWI without the too common uninformed slag upon slag over the temperance movement. Judging from a seat in the future is one of the worst faults of a historian. Almost as bad as disobeying chronology. The authors here simple gather up sources and then unpack the narrative. Fabulous stuff. And not that simple at all.

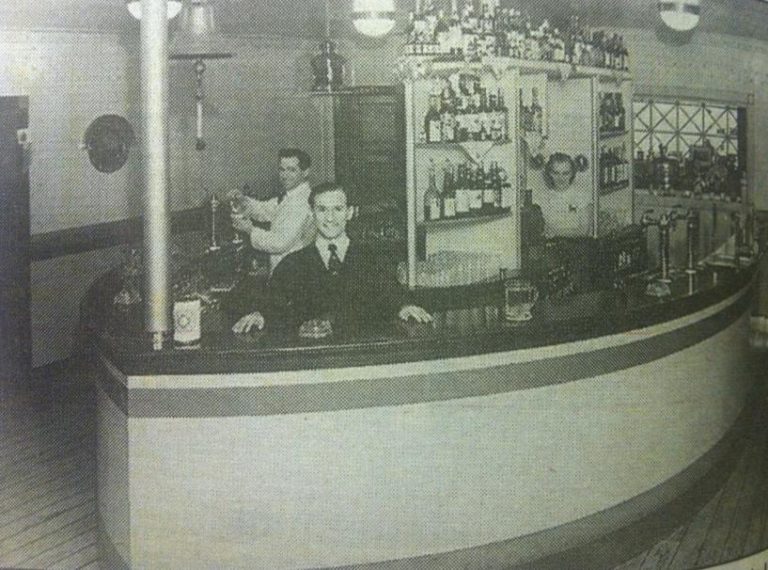

I am taking my time, reading slowing. I am in the chapter on theme pubs, which related to the photo at the top of the page. In 2012, I wrote about the politician’s mother, my paternal great-grannie who goes by “Grannie Campbell” in our family. She loved drink and pubs and apparently she most loved the Suez Canal pub in Largs,*** which was coincidentally my mother’s hometown. The image I am guessing is from the 1940s and the bartender was former world boxing champ, Jackie Paterson. Given the book is about English pubs and not British ones, my submission of the photo did not make the cut. Saddened I was but then heartened by the rigor being imposed by the authors.

Buy this book.

*Somewhere I have an email discussion with Stan about the lack of records even from the early GABF days. Can’t find it. Probably deleted it.

**Including the story of the cousin who claimed Hitler saved his life when the air raid sirens woke his family up, got them running to the shelter only to witness the building explode before the bombs started dropping. Apparently someone had left the gas on.

***I only have one quibble with the book so far in fact – a Largs based quibble. B+B claim that the first espresso machine came to Britain in 1951. Being a child of a child of Largs I am well acquainted withe Nardini’s which opened in 1935. Uncle grew up as pals with Aldo. His Dad had a famous run in with one of the owners over an invoice for pebble dash. Italian ice cream parlours and cafe’s were an established thing even in 1935. Pretty sure they would have had espresso from day one given it also had an American soda bar and an electric dish washing machine.

Confession. I have fed Stan in my home. I have been asked by Stan why he bothers discussing things with me. My name appears in this book. I am very fond of Stan. All of which may influence my opinion of his writings, of this book. Along with the fact that this was a review copy kindly forwarded from the publisher. Can’t help it. Heck, if I run the photo contest again this Christmas I might just give it away as the only prize. I’m like that.

Confession. I have fed Stan in my home. I have been asked by Stan why he bothers discussing things with me. My name appears in this book. I am very fond of Stan. All of which may influence my opinion of his writings, of this book. Along with the fact that this was a review copy kindly forwarded from the publisher. Can’t help it. Heck, if I run the photo contest again this Christmas I might just give it away as the only prize. I’m like that.