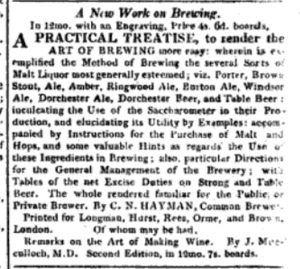

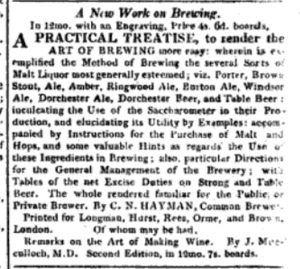

Have my mentioned my last two and a half years have been a bit of a blur at work? The history blogging has suffered. But it’s always the things we hold most dear that fall away, aren’t they. Well, as I expect is the case with you, it’s a bit quieter in the evenings around here so I thought I would pull out some of the delayed research and have a look at Dorchester Ale and Beer starting with a summary of the known information to date. First, if you look at this notice in The Literary Gazette of 1819, you will see something that is apparent from the research: there is both Dorchester Ale and Dorchester Beer. For purposes of this bit of writing, I am not going to get into the distinction but it is important to note that they likely were not synonyms.

Have my mentioned my last two and a half years have been a bit of a blur at work? The history blogging has suffered. But it’s always the things we hold most dear that fall away, aren’t they. Well, as I expect is the case with you, it’s a bit quieter in the evenings around here so I thought I would pull out some of the delayed research and have a look at Dorchester Ale and Beer starting with a summary of the known information to date. First, if you look at this notice in The Literary Gazette of 1819, you will see something that is apparent from the research: there is both Dorchester Ale and Dorchester Beer. For purposes of this bit of writing, I am not going to get into the distinction but it is important to note that they likely were not synonyms.

Dorchester is the county town of Dorset, which sits on the middle of the bottom of England on the Channel. Daniel Defoe praised it in his book A tour thro’ the whole island of Great Britain (1724–26):

“The town is populous, tho’ not large, the streets broad, but the buildings old, and low; however, there is good company and a good deal of it; and a man that coveted a retreat in this world might as agreeably spend his time, and as well in Dorchester, as in any town I know in England…”

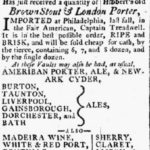

Dorchester was a key departure port for Puritans emigrating to New England in the 1600s. Dorchester beer was popular before and after the American Revolution from at least the 1760s in New York City to the early 1800s. It is not mentioned by Locke in 1674. There was a song about it published in 1784 praising its power to even sooth political disunion. Coppinger described its ingredients in this way in the 1815 edition of his fabulously named book The American Practical Brewer and Tanner:

-

-

- 54 Bushels of the best Pale Malt.

- 50 lb. of the best Hops.

- 1 lb. of Ginger.

- ¼ of a lb. of Cinnamon, pounded.

So, a spiced pale ale says he. You can figure out the 54 bushel to 14 barrel ratio but his version of it does not look like super strong stuff. That would seem to go against the cross-Atlantic shipping market for it so we can think about that a bit more. Or we can turn to North American’s best beer writer who doesn’t write book nor blog, Gerry Lorentz, who added a great whack of information in a comment left at this here blog posted in October 2018 which I add here in full simply because I can:

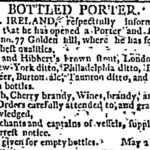

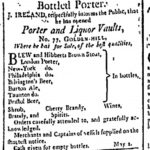

I’m sure that Dorchester beer probably didn’t stay constant over the centuries. Coppinger’s recipes contain a long list of additives, so that fact that he says Dorchester beer contained ginger and cinnamon probably doesn’t amount to much. Friederich Accum indicated that “Dorchester Beer is usually nothing else than Bottled Porter,” this coming after a discussion of Old Hock, or white porter. In Observations on the Diseases in Long Voyages to Hot Climates (1775), John Clark also indicated that Dorchester beer was similar to porter. He discussed “country beer,” noting it as one of “the usual diluters” of meals for the fashionable sort in India: “Country beer is made by mixing one part Dorchester beer, or porter, with two or more parts of water.” Others writers viewed Dorchester beer as similar to brown stout. One early twentieth-century researcher looking to get more information on Dorchester Beer put out a question in Notes and Queries in 1905 asking about a footnote in William Gawler’s 1743 poem, Dorchester, that indicated that “an eminent Dealer in Dorchester Beer, now living in London, reckons amongst his Customers the late Czar, the Kings of Prussia and Denmark, as well as his late and present Majesty of Great Britain,” which points to a Baltic trade similar to porter.

Both William Ellis in the London and Country Brewer (1837) and John Farley in The London Art of Cookery, 7th edition (1792) point out the “chalky water” used in making Dorchester beer. Farley writes that “The Dorchester beer, which is so much admired, is, for the most part brewed of chalky water, which is almost every where in that county ; and as the soil is generally chalk.” So, perhaps it had some Burtonesque qualities to it.

Thomas Hardy probably has the best, and least helpful, description of Dorchester Beer in his book The Trumpet Major, in which he states: “It was of the most beautiful colour that the eye of an artist in beer could desire; full in body, yet brisk as a volcano; piquant, yet with a twang; luminous as an autumn sunset; free from streakiness of taste, but finally, rather heady. The masses worshipped it, and the minor gentry loved it better than wine, and by the most illustrious country families it was not despised.”

Excellent. Clearly a strongish ale. And Gerry is always right. I would but quibble the slightest bit about the qualities “Burtonesque” but I have my own theory about the vomit inducing levels of sulfur that spawned that region’s Satanically hopped styles a generation or two earlier that Dorchester rose into popularity.

In the 1922 book Thomas Hardy’s Dorset, by R.T. Hopkins, we read

Dorchester has now lost its fame for brewing beer. But about 1725 the ale of this town acquired a very great name. In Byron’s manuscript journal (since printed by the Chetham Society) the following entry appears:

“May 18, 1725. I found the effect of last night drinking that foolish Dorset, which was pleasant enough, but did not at all agree with me, for it made me stupid all day.”

A mighty local reputation had “Dorchester Ale,” and it still commands a local influence, for this summer I was advised by the waiter of the Phoenix Hotel to try a bottle of “Grove’s Stingo” made in the town. It is a potent beverage–and needs to be treated with respect, to be drunk slowly and in judicious moderation.

Hopkins continues with the same passage from Thomas Hardy that Gerry L. noted in his comment, above, as well as others from Hardy as well as a mid-1700s song “The Brown Jug” that references a Dorchester Butt as a measure of at least one lad’s girth.

Acknowledging the love-hate relationship we have with records, the earliest i have found Dorchester Ale is recorded as being delivered to North America relates to a shipment to Virginia mentioned in a letter dated, oddly, June 28th and July 25th 1727 from one Robert Carter to Edward Tucker, the latter of whom died in 1739, merchant of Weymouth, Dorset who served as mayor in 1705, 1716, 1721, 1725, and 1735, and also as a member of Parliament:

…Your Portland is gon to York to fill up I have Six hhds of my Crop Tobbo: on board her which Sent you a bill of Lading had Russell bin at liberty to have Sent a Sloop for this Tobbo: he might have got redy for this Fleet I must desire you to Send me in the next year in one of your Ships a hogshead of your fine Dorchester Ale well and Carefully bottled of and under very good Package Your Master Britt will tell you how I was abused in the last. The Southam Cyder the Portland brought me I doubt will never be fine it is not yet Bottled If you can Send me a hogshead of it in bottles that is right good Such as I had two Years ago, it would [be] Acceptable but in Cask I will have no more I am with a great deal of Sincerity…

Hmm… it is fine and worth being shipped. In 1752, Frances Monday was before the judge in London’s Old Bailey indicted for that she assaulted John Hall and stole from him one half guinea in gold. The evidence of Hall begins thusly:

Last Thursday se’nnight I had been in the Borough, staid late, and was in liquor. I could not get into my lodgings in Grey’s-Inn-lane. I was going from thence to Westminster to an acquaintance there, and passing by the new church in the Strand this woman came cross the way to me and asked me to go with her and drink some Dorchester ale. I went to a place which she said was the Black Swan between the new church and Exeter Change. I drank but one glass of beer. She then asked me to give her some shrub. which I did, and a bottle to take home with her.

Ms. Monday was acquitted based on her alternate version of events, backed by witnesses: “The gentleman made me a present of it. After he had what he desired of me, he said he would have it again, or he’d swear a robbery against me.” So… perhaps a sort of beer that was name dropped perhaps to show a bit of unwarranted class?

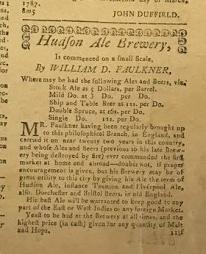

In his MA thesis for the Université de Sherbrooke submitted April 2014, Mathieu Perron stated that Dorchester ale (or beer) was mentioned among numerous other beers in the notices published in La Gazette de Québec during the early years after the fall of New France:

De 1764 à 1774, sur 28 mentions relatives à la bière dans les petites annonces de La Gazette de Québec, 15 occurrences appartiennent à la catégorie « Porter », le restant étant réparti entre différents Malt Liquor. Ces bières (Dorchester Ale/Beer, Yorchester Ale, Taunton Ale, Welch Ale) aux degrés d’alcool élevés, génèreusement houblonnées, raditionnellement consommées par les classes moyennes anglaises, attestent du transfert des habitudes de consommation chez les classes marchandes de la province…

Fabulous references to the variety available to the military elite in that garrison town. And I need to see the ad for “Yorchester” ale now.

Further south, in his diary of 1775-76, the Reverend Dr. Samuel Cooper, pastor of the Brattle Street Church in Boston, Massachusetts – a bit of a coffee fiend – records being treated to “a Glass of Dorchester Ale” on one occasion as he made his way around his fellow revolutionaries in Boston during its bombardment by the British.

After the war, as part of reparations claims which were made with various degrees of success, Henry Howell Williams a 1775 tenant on Noddles Island in Boston Harbour claimed for goods “Destroyed by a Detatchment of the American Army or Carried off by said Detatchment, for the Use of the United States” claimed just in terms of the liquor in his cellar:

| 3 |

Barrls. Cyder 36/2 Q. Casks Wine 220

1 Dozn. Ditto Bottled |

1412.– |

| 1 |

Hamper Dorchester Ale. 6 Dozn. Excellent Cyder |

3.16.– |

| 3 |

Dozn. Carrl. Wine 1 keg Methegalin Sweet Oyle &c. |

6:4:– |

| 2 |

Hogsheads Old Jamaica Spirit 231 Gallns @ 5/- |

57.15.– |

| 3 |

Hogsheads New Rum Just got home from the

W. Indies Quanty. 234 Gallons a 3/4- |

39:0:0 |

Which seems like a lot – and also places Dorchester Ale in fine company.* And on both sides of the Revolution in Puritan Boston, a century and a half after being founded by Dorset folk.

At about the same time back in England but on the same end of the cannon demographically speaking as Mr. Williams of Noddles Island, we read about a pleasure garden named Jenny’s Whim in the Pimlico area of London, “a very favorite place of amusement for the middle classes”:

This feature of the garden is specially mentioned in a short and slight sketch of the place to be found in the Connoisseur of March 15th, 1775:—”The lower part of the people have their Ranelaghs and Vauxhalls as well as ‘the quality.’ Perrott’s inimitable grotto may be seen for only calling for a pint of beer; and the royal diversion of duck-hunting may be had into the bargain, together with a decanter of Dorchester [ale] for your sixpence at ‘Jenny’s Whim.'”

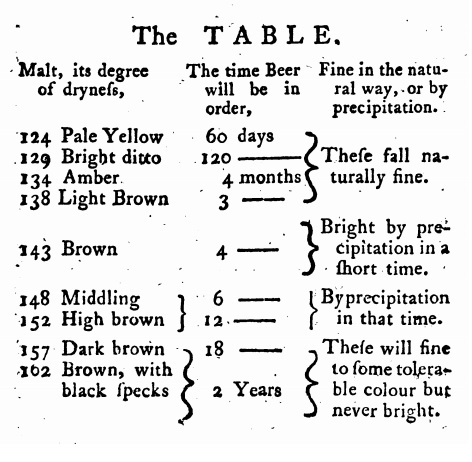

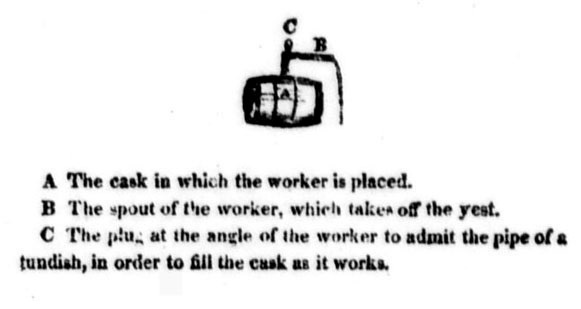

Then things get all scientific. In the 1797 essay “Experiments and Observations on Fermentation and Distillation of Ardent Spirit” by Joseph Collier the pre- and post-fermentation densities of four type of beer are described: Porter, Ringwood Ale, Dorchester Ale and Table Beer. It is interesting. Of course it is. If it was not interesting why would I have mentioned. it? The author uses a “saccharometer” like this. Without knowing the details of the calibration or the scale, the relative ratio is enough to tell us that Dorchester is sweet and a bit strong, a bit more than double that of Table beer. Dorchester drops 39 degrees of the “whatever scale” where Table beer drops 18. Ringwood drops 44 degrees but has a final gravity that is two-thirds of Dorchester. Notice too that these are “the most celebrated malt liquors” – which is interesting.

Then things get all scientific. In the 1797 essay “Experiments and Observations on Fermentation and Distillation of Ardent Spirit” by Joseph Collier the pre- and post-fermentation densities of four type of beer are described: Porter, Ringwood Ale, Dorchester Ale and Table Beer. It is interesting. Of course it is. If it was not interesting why would I have mentioned. it? The author uses a “saccharometer” like this. Without knowing the details of the calibration or the scale, the relative ratio is enough to tell us that Dorchester is sweet and a bit strong, a bit more than double that of Table beer. Dorchester drops 39 degrees of the “whatever scale” where Table beer drops 18. Ringwood drops 44 degrees but has a final gravity that is two-thirds of Dorchester. Notice too that these are “the most celebrated malt liquors” – which is interesting.

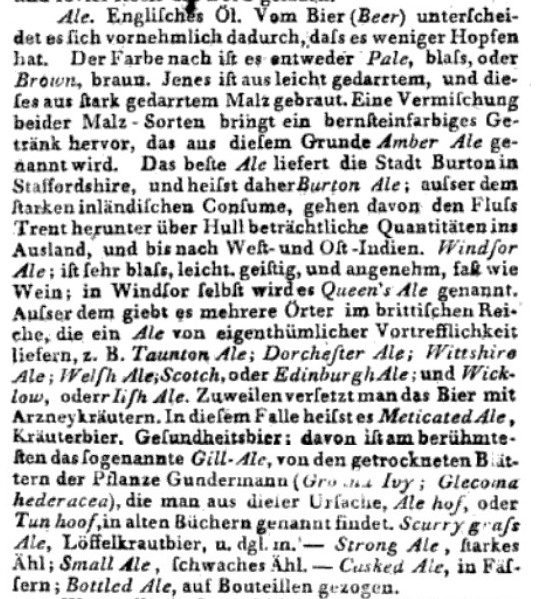

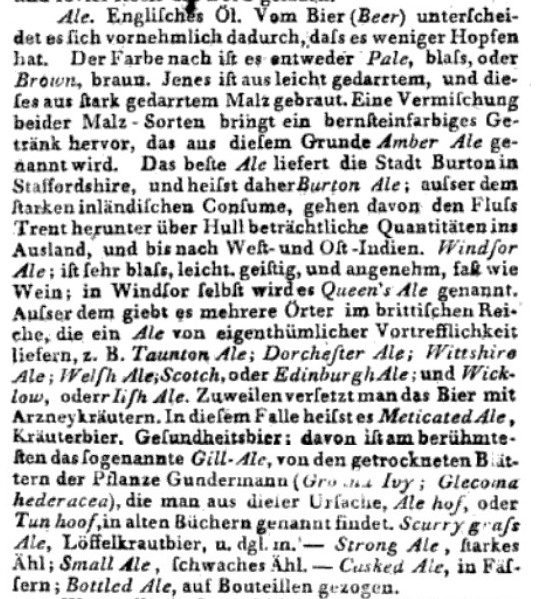

In an 1816 German text entitled Jenaische allgemeine literatur-zeitung, Volume 3, it is listed in another list of English ales. I include the whole passage because it’s pretty interesting as a snapshot of the times. Ron or someone cleverer that I will be able to translate but quite neato to see the references to Queen’s ale and Wittshire ale .

In an 1816 German text entitled Jenaische allgemeine literatur-zeitung, Volume 3, it is listed in another list of English ales. I include the whole passage because it’s pretty interesting as a snapshot of the times. Ron or someone cleverer that I will be able to translate but quite neato to see the references to Queen’s ale and Wittshire ale .

More science. In 1829, Dorcehster Ale is listed in the book Description and Use of the Brewer’s Sacchatometer as having a “proportion of alcohol” of 5.56 which placed it below Burton and Edinburgh Ale and above London Porter.

Does it start to become faded? After his fall from grace and the financial support of the Regent, Beau Brummell exiled in Calais in the 1820s was said to drink it according to this 1860s account and an 1855 article in Harpers:

Not even for Lord Westmoreland, his creditor for frequent loans, would the Man of Fashion consent to “feed” at an earlier hour. Being a pauper, Dorchester ale, with a petit verre, and a bottle of the best claret were his usual beverage when alone; but he counted largely on invitations to dinner from passing Englishmen. As he grew older, gluttony grew upon him; ho had not the heart to refuse an invitation, no matter what the hour of ” feeding.”

In Slaters Directory 1852/3 it was written:

The spinning of worsted yarn and the manufacture of woollen goods , formerly ranked as the staple here; but these branches have greatly declined, if they are not entirely lost – blanketing and fiuscy being the only articles now manufactured. Dorchester ale has long been famed, and it still maintains a superior character; the mutton of this district is liekwise held in great and general estimation.

The same source for that text has a helpful page on one Robert Galpin of Fordington in the County of Dorset, Brewer, which give a helpful sense of scale of brewing operations then or at least his operation at the time.

What to make of it all? Dorchester Ale / Beer appear to be a Georgian thing that arcs in parallel to Burton and Nottingham, coming after 1600s and early 1700s strong English ales like Lambeth, Derby, Hull and Northdown/Margate. Like Taunton, it is exported to North America and perhaps elsewhere in the colonies. It is not as strong as others and seems to have chalky water with a pronounced residual sweetness. Premium while not necessarily being a headbanger.

Interesting also to note how these strong pale ales named after the city or region in which they were brewed generally (but not exclusively) fit between (i) the Medieval and Tudor pattern of naming beers according to their heft: half-penny, two penny, double double and (ii) the brewer branded beer, scientifically made proto-styles we start seeing beginning in the 1800s. Like the climactic observations on the reason French bread in great in the recent excellent article in the New Yorker “Baking Bread in Lyon“, they would have been remarkable for some local characteristic that set them apart.

I will have to organize these posts on English Stuart and Georgian era regional strong pale ales into some better categorizations. They need an umbrella term. They are not styles in the same sense as their predecessors or their descendants. But they were clearly recognizable and sought out for their prestige.

*And I trust that table rendered well at your end of the internets.

Another week in lock down. What is there to say? Things are moving along a bit of a path, maybe showing a bit of the light at the end of the tunnel. Maybe. I hope the world hasn’t turned too upside down where you are. Things are looking a bit better in Rye, England where as we see above James Jeffrey has created the “Beer Delivery by Stonch!“* service. I’m not sure of the legalities of it all but how lovely to get a couple of pints of fresh drawn ale delivered from the pub. We’ve had new laxer laws pub in place here so no doubt there are more novel opportunities out there to be discussed.

Another week in lock down. What is there to say? Things are moving along a bit of a path, maybe showing a bit of the light at the end of the tunnel. Maybe. I hope the world hasn’t turned too upside down where you are. Things are looking a bit better in Rye, England where as we see above James Jeffrey has created the “Beer Delivery by Stonch!“* service. I’m not sure of the legalities of it all but how lovely to get a couple of pints of fresh drawn ale delivered from the pub. We’ve had new laxer laws pub in place here so no doubt there are more novel opportunities out there to be discussed.

In an

In an