As threatened and then oddly certified, I am stepping in for July as Stan has scampers off somewhere. And it seems Boak and Bailey are putting their feet up, too. So my July 2nd and a bit of the 3rd will be spent pounding the keyboard for your sideward glance – instead of focusing on the can of Bud and Coors Light like most beer loving Canadians will be doing. No rush. I have to make the best use of that lawn chair out back. Hmm… has there been anything going on worth discussing?

Wine News

As is Stan’s habit, I begin the week’s highlights with news from Clarence House. Prince Charles and herself spent a part of last Friday about an hour’s drive west of me partaking of the wines of Prince Edward Co., Ontario. I have written a few posts in the past about the region which you may wish to review before checking out the story as covered by the UK’s Daily Mail. Excellent exposture to the greater world market likely means my local prices go up. Thanks, Chuck.

In other wine news, Eric Asimov in The New York Times has made the case for simplicity and pleasure in his regular “Wine School” column:

That is especially true with the thirst-quenching wines we have been drinking over the last few weeks. These easygoing wines are primarily focused on the No. 1 task of any wine: to refresh. They do so deliciously, but these wines don’t offer much to think about. They are the lawn-mower beers of wine, ready to stimulate, energize and invigorate. They provoke physical reactions, and do not leave much room for contemplation.

I can hear the teeth grinding but being honest – for 99% of the time 99% of beer drinkers don’t sit around and contemplate 99% of their sipping anyway. Thinking about such things might include less thinking about such things. Think about it.

The Logo

Once again, the US Brewers Association PR committee has made a bit of a botch of a well meant bit of communications. At the start of the week, they revealed a new logo for their organization, then limited its use to only members who signed the special pledge and watched as their plans for market share demarcation got ripped. Given these folks came up with the fabulous failure of “craft v. crafty” what were we expecting? So many fonts for one image – is it five? And that weird outline. And an upside-down bottle.

The really problem the BA faces is that it can’t use the proper word that beer fans are really interested in – local. This is because it has spent a decade chasing the false promise of national craft with truckloads of California beer selling in New York gas stations and corner stores while Maine brewed Belgian-styled ale sell in Hong Kong and Dubai. So, the campaign and the logo have to fall back on second rate concepts.

The key concept in the messy logo is something called “INDE… PEN… DENT” which sits uneasily along with inordinate use of a “TM” and “CERTIFIED” given the limited visual geography. [Note: I couldn’t find the image’s trademark registration when I looked for 47 seconds and nothing about the logo relates to certification.] The problem with “independent” as a core message is that big industrial macro is independent too and the diversity of small local brewers can hardly be expressed with the “one ring to rule them all” approach that centralized trade industry branding offers. Plus anything can be “independent” can’t it.

Jeff Alworth takes a different approach which is quite compelling, separating message from branding. He argues that by moving away from “craft” and embracing “independent” as the core concept, the BA is taking back control of the debate. Bryan Roth also explores “independence” more from just the branding angle. But, for me, both these approaches (as both Jeff and Bryan state) are not without long term issues. Consider Mr C. Barnes at The Full Pint who is even less hopeful.

The Video

This is even sillier. Andy called it correctly when he called it “whining and whinging.” You may have more thoughts on the thing but I don’t see why anyone would bother. Why make that sort of ad when you have made this fabulous one?

Other things

The Sun newspaper-like thing reports that hipster craft is causing an inflationary effect on the price of lager. Who saw that coming?

The Sammy Smith “no swearing in our pubs” rule has led to at least one pub closing up for an evening due to naughty bad bad people being rude. Pete Brown, no fan apparently, called Humphry Smith, the head of the company behind the scheme to wipe out bad language the “nastiest, most unpleasant person in the brewing industry” by way of his introduction to a story on Humph in The Guardian which discloses this tidbit:

Smith’s eccentricity is the source of local legend and seems to know no bounds. Regulars inside Smith pubs claim he habitually dresses up as a tramp and poses as a customer to make sure his rules are being enforced. Punters in the Commercial Inn in Oldham claim Smith once sacked a bar worker for not handing him the correct change – another tale of summary sacking it has not been possible to confirm.

Quite the nut – but it is his ball so he can take it home whenever he gets in a huff, I suppose.

Finally, happy to report that the Canada Day long weekend was celebrated with Ontario made regional and local small brewery beers from Perth, Riverhead, Beyond the Pale, Great Lakes and Side Launch. Those two gents up there with their Buds? They are the 90%. It’s everywhere.

Fine. That’s enough for this week, Stan. Time to hang up the bloggers smock. Send your complaints and spelling correction suggestions to him via Twitter.

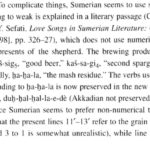

The other day, I read that The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York had freed thousands of images from their intellectual property right shackles for free and unrestricted public

The other day, I read that The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York had freed thousands of images from their intellectual property right shackles for free and unrestricted public