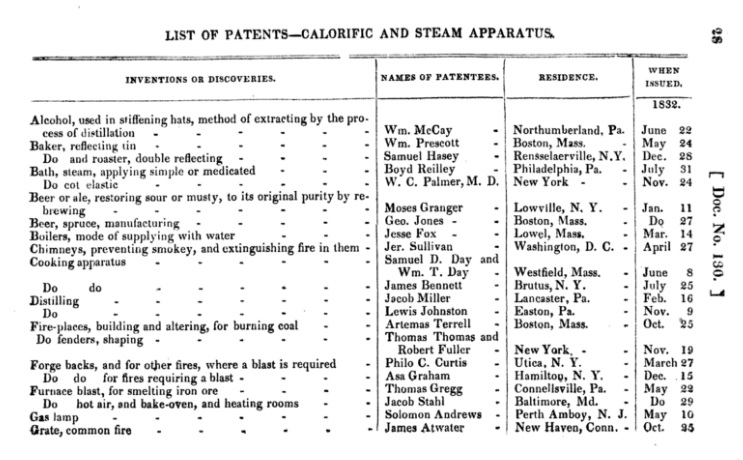

The title of the patent from 1832 is titillating: “US Patent: 6,894X – Restoring sour or musty beer or ale to its original purity by rebrewing.” Sadly the note at the DATAPM data base tells the rest of the story:

The title of the patent from 1832 is titillating: “US Patent: 6,894X – Restoring sour or musty beer or ale to its original purity by rebrewing.” Sadly the note at the DATAPM data base tells the rest of the story:

Most of the patents prior to 1836 were lost in the Dec. 1836 fire. Only about 2,000 of the almost 10,000 documents were recovered. Little is known about this patent. There are no patent drawings available. This patent is in the database for reference only.

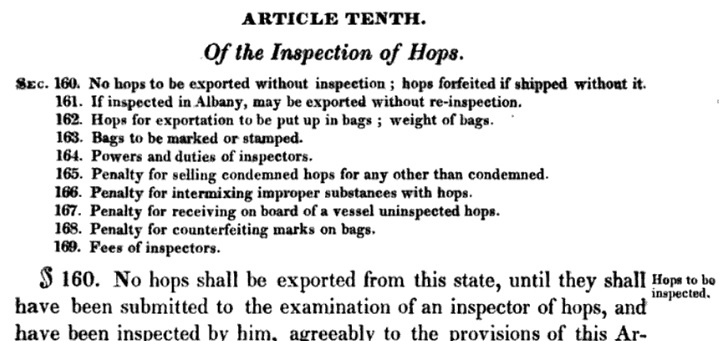

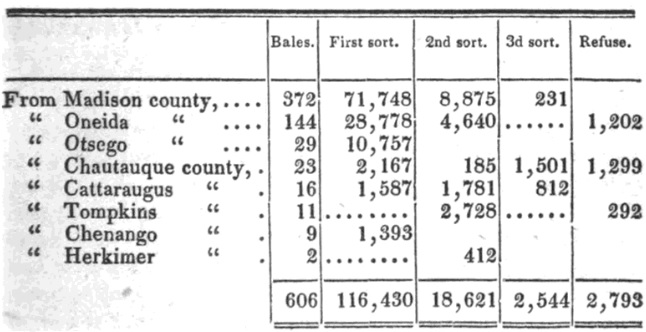

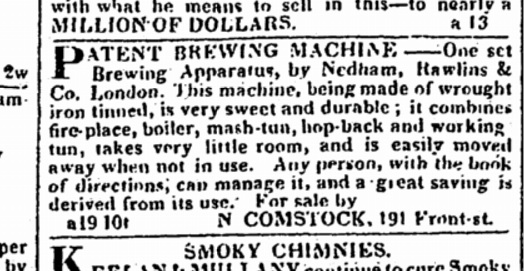

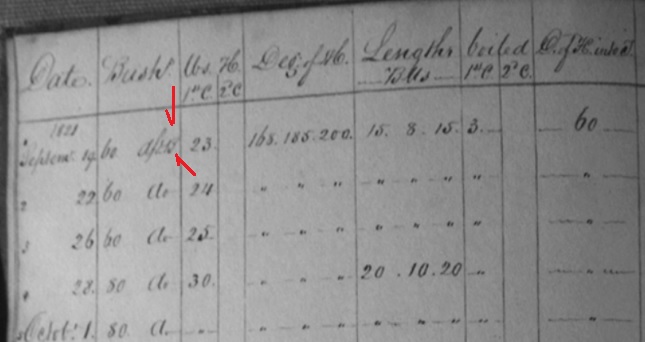

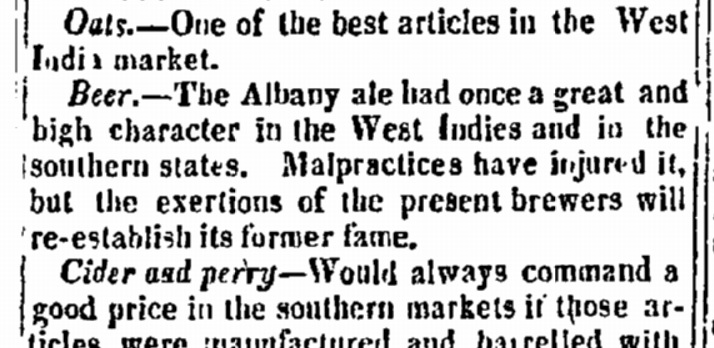

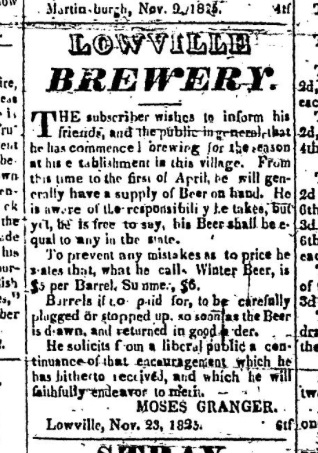

This is sad for us now as well as sad for the inventor, Moses Granger. As you can see above, he started his brewery in Lowville, New York seven or so years before registering his mysterious patent for improving bad beer. The announcement is from the Black River Gazette of 14 December 1825. You can see below from page 28 of the Congressional Series of United States Public Documents, Volume 235 that his patent was issued on 11 January 1832 which means he had to have invented it and then worked on the patent application sometime before that. Notice also that his patent is in a list of “Calorific and Steam Apparatus” which again is a reminder that Steam Beer is a reference to the general introduction of steam powered motors into the brewing trade and not something about the beer itself.

Unlike most of you, I have visited Lowville, New York. It is just about an hour and 45 minutes drive to my south east sitting in Lewis County, the next NY state county to Jefferson which I can see out my office window. It is the home of Lloyd’s of Lowville. My 2005 post on neighbouring Denmark, NY on the hill north of Lowville gives you a sense of the area. Rural limestone Federalist buildings, analogous to our larger urban and military Georgian ones.

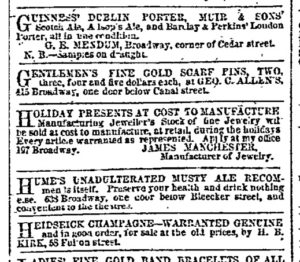

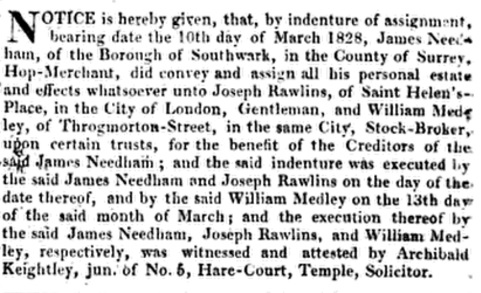

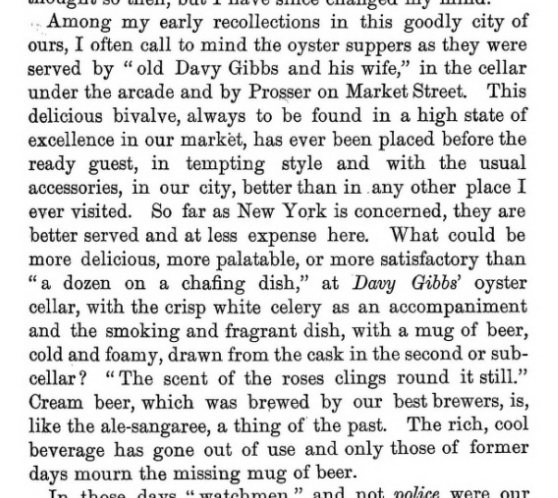

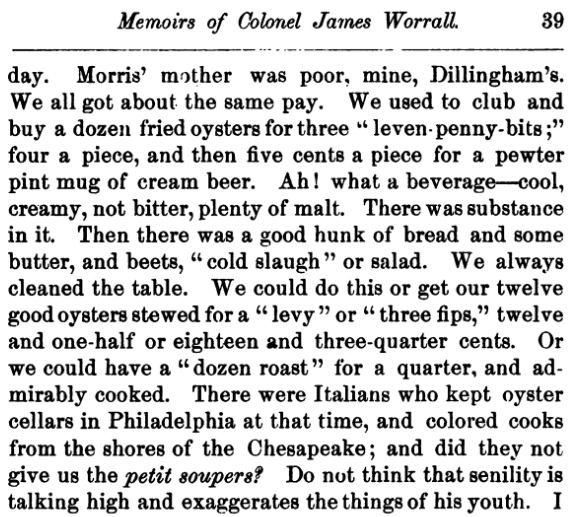

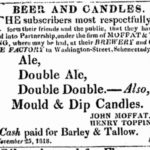

Gary mentioned Moses Granger and this patent in the latest of his further explorations of the odd later 1800s eastern US use of “musty” as a positive term for a class of ale. The patent from an earlier point in time, however, is clearly about the correction of poor beer – restoring it by rebrewing sayeth the patent’s title. “Rebrewing” is an interesting word. In 1818, another two hours modern travel to the southeast in Schenectady, there was rebrewing going on – the last reference I have found to the ancient and famed double double immortalized by Shakespeare. Beer made by reusing beer as sparge water, ramming more power into the wort. It makes a brain smackingly strong drink.

Gary mentioned Moses Granger and this patent in the latest of his further explorations of the odd later 1800s eastern US use of “musty” as a positive term for a class of ale. The patent from an earlier point in time, however, is clearly about the correction of poor beer – restoring it by rebrewing sayeth the patent’s title. “Rebrewing” is an interesting word. In 1818, another two hours modern travel to the southeast in Schenectady, there was rebrewing going on – the last reference I have found to the ancient and famed double double immortalized by Shakespeare. Beer made by reusing beer as sparge water, ramming more power into the wort. It makes a brain smackingly strong drink.

Lewis County, NY in 1825 was still the frontier. See those military installations in my dear old British fort town? Kept back interest in settling NNY as the Erie Canal was opening up WNY. It was settled by the generation after the Revolutionary one, as places like Cooperstown and then CNY started filling up and interests became fixed. Spafford described the place in his 1813 Gazette – and he can be trusted as he was born there. One might read the notice posted by Moses Granger in 1825 that he was the first brewer in Lowville. Spafford shows (at page 50 and 51) that in 1813 there were no brewers in Lewis Co. compared to seven distillers. Jefferson Co. had a ratio of two brewers to sixteen distillers. In 1828, Watertown, Jefferson Co. only had one brewery. The area was awash in rot gut whisky. A rebrewed super strength brewing process might well be worth protecting by way of patent.

I will dig a bit more and maybe post more – and wait for Gerry… again… to correct and add to the story. An excellent thing, too, as by collaboratively assembling what we know the history unfolds. The strange thing is why one would invent such a thing in a frontier setting and then seek the protection of the law – on the one hand just thirty years removed from that log house brewery in Geneva, NY but, on the other, in the era of the scientific brewing of Vassar. An era of great change.