I am working on a relatively new database to me, a newspaper and magazine archive covering a little over the last thirty years. Grinding common beer words through the search engine of any new database is always fun but in the shadowy world of the recent past it can also be surprising. I don’t actually write all that much about the origins of of the micro brewing industry but, as we know, the shifting sands and rearguard revisionist retelling of all the genesis stories should be enough motivation for anyone. And it turns out there are interesting tales to be told from the point in time when “micro” was battling with “mini” and recently deceased “craft” was just a gleam in some PR committee’s eye.

First, set the scene. In Albany, New York’s Times Union of 16 July 1986 we have the staff byline story “Abrams Sues Big Breweries” – this particular Abrams being New York State Attorney General Robert Abrams:

The state attorney general filed an anti-trust suit in federal court Tuesday charging the four major beer breweries and their distributors have virtually suffocated competition and created unnaturally high 6-pack prices. The suit filed in U.S. District Court in Brooklyn names Anheuser-Busch Inc., Miller Brewing Co., G. Heileman Brewing Co. Inc. and the Stroh Brewery Co. breweries and the New York State Beer Wholesalers Association, which he charged control 80 percent of the New York state beer market. The four companies distribute almost every big-name beer in New York, including Budweiser, Michelob, Miller, Schlitz, Schaefer, Colt 45 and Schmidt.

The story states that the lawsuit, which charged distributor and breweries were engaged in an actual conspiracy to control the beer market prices. The interesting thing is that this is the sort of thing that big craft suggests it triggered but this story is effectively pre-micro.

In another tale from that same month we read, again in the Times Union, a story of accusation. In the 7 July 1986 edition, we can find the headline “Boston Beer Seller Claims 3 European Imports Impure” which is pretty funny given there have been false and well proven accusations about competition in the brewing industry since, well, pretty much since beer was invented. The story by Bart Ziefler of the Associated Press starts in this way:

A tiny Boston beer company is taking on two giant international brewers, claiming the top European imported beers couldn’t be sold in West Germany because they don’t meet that nation’s beer purity law. In a series of radio and newspaper ads, Boston Beer Co. has challenged the the quality of the Beck’s, St. Pauli Girl and Heineken beers sold in this country. Beck and Co. of Bremen, West Germany, which brews Beck’s and export- only St. Pauli Girl, denies the claim. Netherlands-based Heineken, brewer of the No. 1 import, acknowledged that its contains corn and they don’t try to sell it in West Germany, according to the Boston Business Journal. “It’s sort of common knowledge among brewers that the beers are doctored,” said James Koch, whose company began selling Samuel Adams beer a little more than a year ago. “If you’re going to bring beer from that far away and have it drinkable, you’ve got to do something to stabilize it.”

Really? Corn as the crisis in craft? Excellent. Can’t we just admit we like corn sometimes? Is this PR campaign where the phobia related to the one ingredient “whose name may not be spake” came from? Sweet last line in which Koch states that he said he hoped to make Sam Adams truly a Boston beer next year by opening his own brewery. Correct me if I am wrong but, according to wiki wisdom, the brewery wasn’t bought for another eleven years and it was located in Cincinnati.

The Buffalo News of 8 November 1991 included a particularly excellent “state of the nation” report by Dale Anderson from the 1991 Microbrewers & Pubbrewers Conference at the Hyatt Regency in that fair City… two months before, in September. Under the lengthy headline “A Little Beer – Microbreweries, Producing Specialty Beers in Small Quantities Are The Talk Of The Industry” we learn a lot of things… and not just that there was the term “pubbbrewers”:

1. “Two American breweries — Sierra Nevada in California and Red Hook in Washington — actually have outgrown the “micro” designation.”

2. “The biggest concentration of brew-pubs on the continent, meanwhile, is in nearby Ontario, where there are about two dozen in the Toronto area alone.”

3. “These small-scale operations have little effect on the big brewers… Instead, they have moved in on the imported specialty brands.”

4. “One reason Queen City chose to brew at Lion is that it could put foil wrapping on the necks of the bottles and other breweries couldn’t. “We sat back and said we didn’t want to run a microbrewery with a pub attached,” Smith says, “so we followed the path of Jim Koch with Samuel Adams in Boston. The tough part is predicting four or five weeks ahead of time what we’re going to need.”

You can click on the article for more but it is interesting that the acknowledgement of out-growing the category as well as contract brewing was so openly stated and presented simply as a sign of success.

Less familiar perhaps than the other stories is the weird 2002 tale of the “Sex For Sam” sponsored by Samuel Adams Beer in which “prizes were awarded to people who had sex in unlikely public places.” Unlike the many references to Mr. Koch the Ascendant in the media of the time, this is not one that weathers the passage of time so well. In the New York Post of 7 November 2003, William J. Gorta and Bill Hoffmann reported the story a year later after events in question – when the resulting criminal processes were concluded:

The Virginia woman who scandalized St. Patrick’s Cathedral by having sex in the pews as part of a sleazy radio stunt that revolted the city will not go to jail. Loretta Lynn Harper, 36, was sentenced to 40 hours of community service as part of a plea deal in which she admitted to disorderly conduct. Prosecutors took pity on Harper because her boyfriend, 38-year-old Brian Florence – her sex partner in the church tryst – died suddenly of heart failure last month.

Turns out the great idea was a joint project between Boston Beer and the soon to be fired WNEW-FM shock jocks Opie and Anthony. An FCC fine of $357,000 was levied against the radio station. The final two lines of the story is classic:

WNEW had no comment on the sentencing. A rep for Opie and Anthony and Sam Adams President Jim Koch did not return calls.

Wise. But a little more detail is provided in a gossip column in the New York Daily News of 29 August 29, 2002 which I provide in full for reasons of review of the delightful manner in which the gossipy tidbit was framed:

Opie and Anthony had a beer buddy rooting them on in the studio while they encouraged the St. Patrick’s Cathedral sex stunt that got them canned. Jim Koch, the head of Boston Beer Co., admitted he was on hand during the taping and issued an apology on the company’s Web site Monday. “We at the Boston Beer Co. formally apologize to all those upset or offended by the incident on the Opie and Anthony show and by our association with it,” wrote Koch. His company backed the show’s “Sex for Sam” contest, which promoted a trip to Boston to the company’s annual festival for couples who had public sex. The Samuel Adams brewer even called Lou Giovino, the Catholic League’s director of communications, to apologize. “I spoke with him twice since Monday,” Giovino told us, “And we’re satisfied with his apology.” But Giovino didn’t seem content when we told him he could listen to Koch’s studio hooting on the Smoking Gun’s Web site. “Oh, boy,” he sighed.

The past is a foreign country – they do things differently there. “Oh boy,” indeed.

One last tale. A little less… ripe and perhaps more in tune with where the future was actually going. In the 2 November 1996 issue of Newsweek magazine, there was a short piece headlined “Hobbies – It’s Beer O’Clock” in the regular Cyberscope column authored by Brad Stone and Jennifer Tanaka.

Seems like it’s hardly ever Miller time anymore. Now that America has developed a taste for microbrewed beer, The Real Beer Page (http:realbeer.com) should find a natural audience. It’s a one-stop destination for dozens of links to microbrewery home pages, beer Web zines and a database of brew pubs with a search engine to help you find one in your neighborhood. Cheers.

Dozens! Imagine. Particularly sweet is the note that the caption to an accompanying image was “Suds on the Menu” because no one loves an early web pun more than me. I also like the reference to “beer Web zines” which what I really should have called this place – A Good Beer Web Zine. Where are my Hammer Pants?

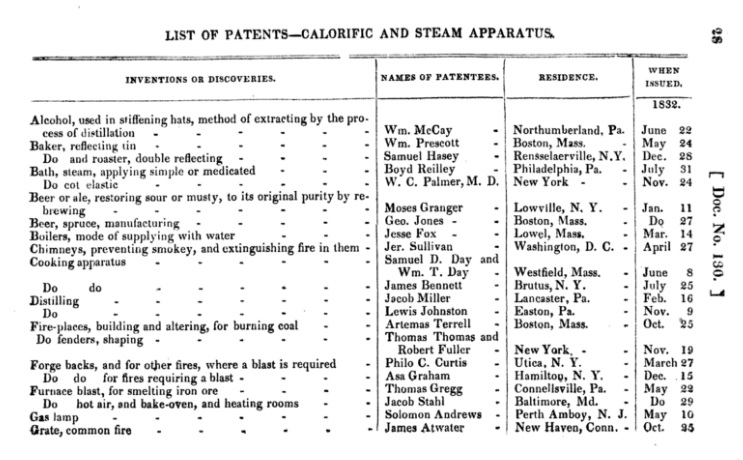

The title of the patent from 1832 is titillating: “US Patent: 6,894X – Restoring sour or musty beer or ale to its original purity by rebrewing.” Sadly the

The title of the patent from 1832 is titillating: “US Patent: 6,894X – Restoring sour or musty beer or ale to its original purity by rebrewing.” Sadly the

Gary

Gary