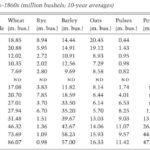

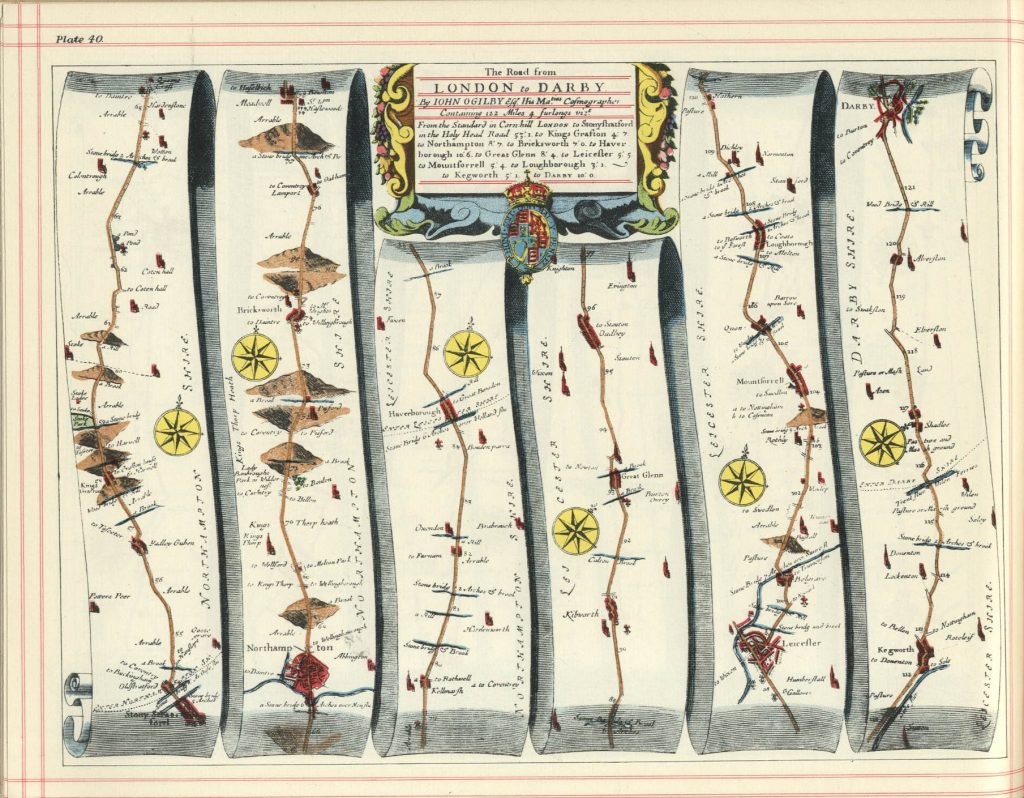

I was thinking I needed to write a post about Derby ale. The other week when I wrote this post with a bit more information about some of the other great 1600s strong ales Margate and Northdown and Hull and Lambeth, I knew I needed to have a look at Derby. I even had this lovely map, above, of the road to London from Derby* of the era, John Ogilby‘s atlas of 1675 working on the premise that it was going to tell me about how the beer got from Derby to London. A lovely map.

But then I began to read more and realized that I needed to understand more about the roads and the river Trent, the fuel crisis from 1550 to 1700 and period barley varieties. This is because, it strike me, Derby ale might just be the combination of at least three unique elements coming together as opposed the factors which caused its competition. It might actually be quite unlike them altogether – an ale named for a municipality which is not necessarily the municipality in which each example was brewed.

Then after a week of assembling the post and hitting 2500 words, I realized I need to break this down into manageable bits. So, in this post I am going to discuss factors related to Derby ale in the 1600s related to transportation and malt kilning while leaving other factors to another. Hopefully this will be more helpful even if, as Stan commiserated with me, after viewing yet another text “getting it wrong” I am also well aware no one much reads the history posts. Which is fine.

Factor One: Goods and Navigation on the Trent and Derwent

For a beer to be worth the cost of transportation, it is reasonable to expect that it had to have an advantage making that cost worthwhile. Advantage is key. We know that the poet Andrew Marvell obsessed, in his side gig as a Member of Parliament for Hull from 1658 to 1678, over the effect taxation was having on his constituency’s brewing industry. Given its 1600s southerly competition were all much closer, any imposition on the price of Hull ale would affect the position of Hull ale exports to London greatly.

The same is true for other great beers of the pre-Georgian era. In this post, I discussed how the opening of the Trent in 1711 by, George Hayne made the Trent navigable to the southwest of Nottingham leading to, in issue 383 of The Spectator from 20 May 1712, the early journalist Addison notes going out for the day in London with his pal Sir Roger to drink Burton ale. New and improved transit makes for new an improved drinks choices for the wealth drenched.

The city of Derby sits on a tributary of the Trent, the north to south flowing river Derwent** near where the rivers meet. Historically, the Trent was not navigable or at least not safe or perhaps reliable upriver from Nottingham, 13 miles to the east of Derby. According to this source, the Derwent was opened to navigation from Derby to the Trent at Wilden Ferry in 1721 under an Act passed the previous year. After the 1600s. In 1699, the same source states that the authority to open the Trent from Wilden Ferry to Burton was granted by Parliament to Lord Paget*** but only exercised, as noted above, in 1711. Again, after the 1600s. So, following what might today be a 16 miles portion of the A52, goods would have been carted from Derby to Nottingham for loading on watercraft for London.

But would they? It is clear Derby ale is well known in London in the 1600s well before the opening up of the Trent and Derwent. Pepys drank it in the 1660s. The fame of Derby ale has been argued to be tied to the development of coke during the English Civil War in the 1640s. Hornsey, too, describes in his now ten year old History of Beer and Brewing how Derby produced fine ale by the mid-1600s. So before the rivers were made open in the 1700s, Derby ale was known. Meaning it had to have been, at least, moved by a mix of transport modes.

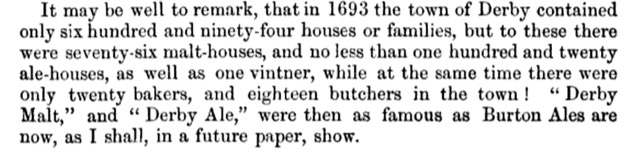

Notice, too, the scale of operations. As Martyn pointed out in a 2009 post, the historian RA Mott, writing in 1965, said of the town:

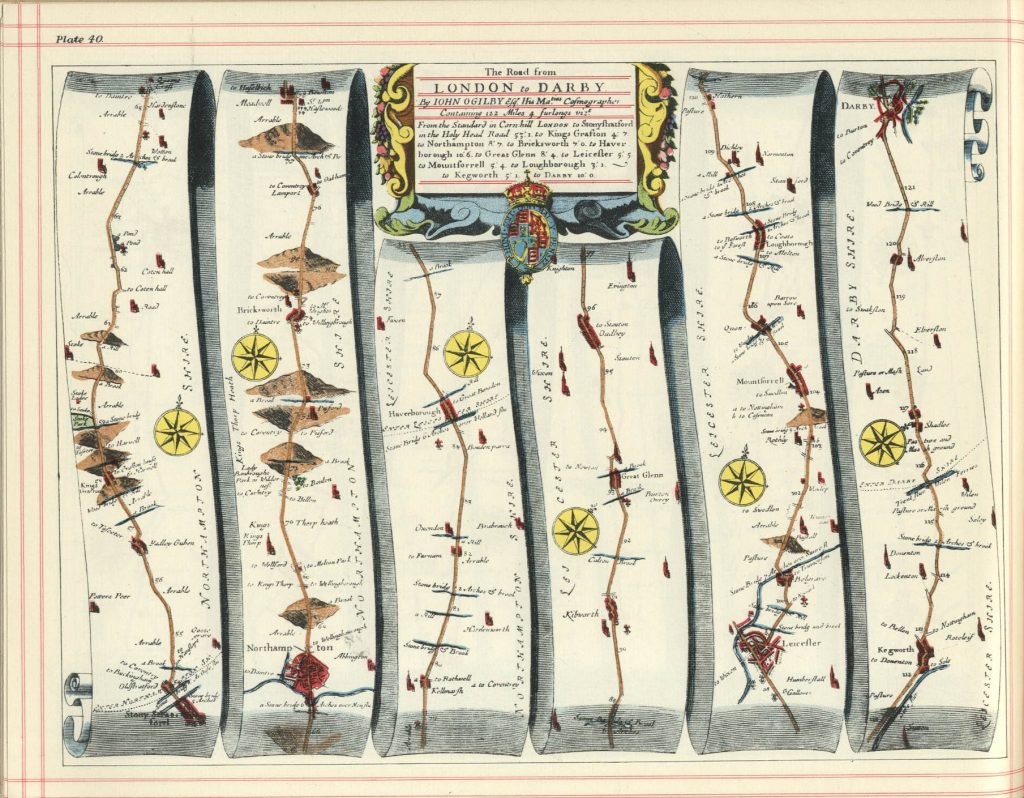

“In 1693, when there were 694 family houses, there were 76 malt houses and 120 ale houses, so that malt-making and brewing must have been the dominant occupations. A list of those occupied in the wool, leather, wood, metal and stone trades and the normal supply occupations left room for some 200 maltsters and brewers. Much malt was carried to the ferry on the river Trent, five miles away, whence it could go by water to London; 300 pack-horse loads (each of 6 bushels which each contained 40lb) or 32 tons were taken weekly into Lancashire and Cheshire.”

Which, if you think about it, is interesting. Pre-aggregation. If there are 76 malt houses, there isn’t one central mammoth Derby Malting Co. Similarly, there are 120 ale houses, not one or five big breweries. What is going on is cottage industry production. One alehouse or malt house for every 3.5 households on average. A large number of small operations coming together to make one product. This is different from, for example, the contemporary competition out of Northdown which depended on the reputation of one brewer, the “inventor” Mr. Prince.

Wikipedia tells us that stone barns and warehouses still exist at Shardlow, described as an inland port developed before the improvement of navigation on the Trent. Shardlow sit on the north side of the Trent “about 6 miles southeast of Derby and 11 miles southwest of Nottingham.” It is just to the west of where the Derwent enters the Trent. This is a heritage listing for a 1700s Shardlow barn which sits on “the London Road.” Here is another in the parish of Shardow on Wilne Lane, Great Wilne which sits to the east of Shardlow itself. This is a survey of bats living at another. The regional tourism development agency describes the key feature of Shardlow today thusly:

Shardlow is one of the best-preserved inland canal ports in the country… A walk along the canal towpath brings you into contact with many of the old buildings of the Canal Age. Mostly now used for different purposes, but still largely intact: the massive warehouses that once stored ale, cheese, coal, cotton, iron, lead, malt, pottery and salt; and the wharves where goods were loaded and unloaded.

A district with period barns and warehouses for storing bulk grain, malt and other goods indicates something. That it was a hub of storing bulk grain, malt and other goods. A point of aggregation.

Click on the thumbnail to the right. Notice the lay of the land. A narrow winding river in boggy land to both sides of the Trent Canal and the river itself. The Derwent also twists away to the north. No wonder getting goods through this area was difficult. No wonder statutes of Parliament and great investments were needed to get the goods out of the district in the 1700s.

Click on the thumbnail to the right. Notice the lay of the land. A narrow winding river in boggy land to both sides of the Trent Canal and the river itself. The Derwent also twists away to the north. No wonder getting goods through this area was difficult. No wonder statutes of Parliament and great investments were needed to get the goods out of the district in the 1700s.

So, to get out of town and down to London, Derby ale had to be transported and transported along a long road or a boggy river yet to be improved. Which, like the extra distance Hull ale needed to cover, is a cost that apparently Londoners were willing to bear.

Factor Two: Coke, Straw and Pale Ale

Derby ale is known to be an early adopter of coke kilned malt. Derbyshire, along with being the valley of the Derwent, is part of a fairly southerly coal mining district. A canal was finally constructed in the 1790s to get the coal out. Hornsey also describes in History of Beer and Brewing how Derby produced fine coke by the mid-1600s due to the particular purity and hardness of the region’s coal. Even so, coke was not immediately or universally accepted as a replacement for wood or straw.

Note that, I said above, the generally accepted date of coke being used for the kilning of malt is in the 1640s. But in 1977, an article in Scientific American states “[b]efore the British (sic) civil war of the 1640s, coke was introduced for the drying of malt in connection with the brewing industry.” Before. This appears consistent with contemporary records. In 1637, Charles I of England received the following petition:

61. Petition of John Gaspar Wolffen, his Majesty’s servant, to the King. Your Majesty gave leave to petitioner to make trial of his invention for brewing with a “charked” sea coal, which, as your Majesty has seen yourself, yields no smoke, and will do as readily, and within a little as cheap, as the ordinary way of brewing. Prays licence for brewers of Westminster and other places, questioned about smoke, who are willing to embrace the said invention, to continue in their brewhouses without molestation.

“Charked.” Made dark as if charcoal. Sea coal. Not Derby mined coal. Sea coal is coal gathered on a beach. It was gathered until at least ten years ago in some parts of Britain. An opportunity to make coke with that coal was suggested earlier by a decade. This is an interesting thing. It’s the sort of thing that was interesting to Martyn back in 2009 when he wrote this about coke kilning and Derby ale:

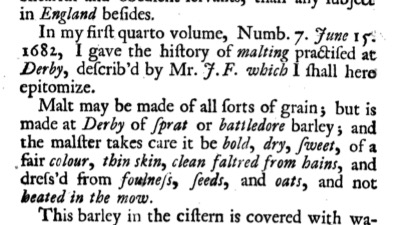

Coke was invented in the North of England (it appears to be a North Country dialect word, originally meaning “core”, as if the “coakes” were the “core” of the coal), apparently in the 17th century. Its use to make malt was first taking place in Derbyshire in the early 1640s, according to John Houghton, an apothecary and part-time journalist, who issued a weekly bulletin in the 1690s and early 1700s, price two pence, called A Collection for Improvement of Agriculture and Trade. In one issue in 1693 he talked about the coal miners of Derbyshire, and added:

The reason of Derby malt being so fine and sweet, my friend thinks is the drying it with cowks, which is a sort of coal … ’tis not above half a century of years since they dried their malt with straw (as other places now do) before they used cowkes which made that alteration since that all England admires.

Note one more thing about that passage from Houghton which Martyn quotes. Coke is the successor to straw. Not to coal. Not wood. Not even charcoal – aka “charked” wood. We have established, in this post from three years ago, that straw had been used for yoinks to kiln lovely pale and un-smoked malt. As Houghton stated in the 1690s: “’tis not above half a century of years since they dried their malt with straw…” Coke is the next fuel, not the first. We need to accept that pale malts either – sun dried and straw kilned – were a thing well before coke. Why wouldn’t there be? Cheap and effective and no one was sitting around glum waiting for the future when coke was going to be invented.

We know that ale was popular, pale and not smokey in the 1690s after coke was introduced as a kilning fuel as Martyn showed in 2009:

[A]nother late 17th century writer, Mr Christopher Merret*, “surveyor of the Port of Boston”, fills the breach, though writing about Lincolnshire, not Derby. In a paper called “An Account of Several Observables in Lincolnshire, Not Taken Notice of in Camden, or Any Other Author”, presented to the Royal Society in 1695-97, he wrote:

“Here Cool are Charred and then call’d Couk, wherewith they Dry Malt, giving little Colour or Taste to the Drink made therewith.”

Pale ale was definitely being made in Lincolnshire in the 1690s from coke-dried malt. Yet earlier than that point, paleness and purity of taste was not created by coke. Over 100 years earlier a similar observation was made, well before the invention of coke by William Harrison, a scholar clergyman, who published his book A Description of England in 1577. Here is a full copy of the text posted by Fordham University in which you will find this:

The best malt is tried by the hardness and colour; for, if it look fresh with a yellow hue, and thereto will write like a piece of chalk, after you have bitten a kernel in sunder in the midst, then you may assure yourself that it is dried down. In some places it is dried at leisure with wood alone or straw alone, in others with wood and straw together; but, of all, the straw dried is the most excellent. For the wood-dried malt when it is brewed, beside that the drink is higher of colour, it doth hurt and annoy the head of him that is not used thereto, because of the smoke.

Chalk is, you will note, pale and also that smoke is associated with wood. Straw kilned malt has the best of both. This was long remembered. In the seventh edition of the The London and Country Brewer from 1759, this is stated under the heading “The Value of Coak”:

It is a most sweet Fuel for drying Malt, the pale Sort in particular, but is best made from the large Pit Coal, which has supplanted the Use of Straw Fuel; and, when it is made to Perfection, it is the most admired Sort of all others.

This passage is in Chapter IX “Of the Fuel to dry Malt, of Malt, &do.” In that chapter, there is a description of techniques and a variety of fuels in a number of English locations including an unnamed town (ie “…in this Town of ____…“), Warminster, Ispswith, Oxfordshire as well as Derbyshire. A number of fuels are described such as aged wood, Welsh coal, coke, fern after a good shower of rain, wheat straw and “Newcastle Coal burnt in a Cockle-Oast.” A successful malt kilning is described as forcing “a quicker Fire to crisp the Kernel, and thereby save Fuel, Time and Labour.” Which means that even as late as 1759, the driving forces behind making malt are financial efficiency through use of available local resources. Standardization of malt kilning fuel has yet to be imposed through full scientific industrialization. Coke is not yet king.

The chapter also includes a specific discussion of Derby ale:

Mr. Houghton’s Observations of Malt-Making – The Reason, he says, why Derby malt does not make so strong ale as formerly, now they make the pale Sort, is because they lay it too thin on the floor to come, by which a great deal is not malted and the rest only Barley turned. Now in Hampshire, he says, the Barley, which is much smaller and thicker skinned, is laid thicker on the Floors, and consequently heats, and all becomes rich Malt and makes stronger Beer with the same Quantity.

The Mr. Houghton being quoted is John Houghton (1645–1705), member of the Royal Society, a newsletter publisher writing in the 1680s and 1690s and an apothecary – as was Louis Hébert in Quebec in the first half of the same century. Proto-scientists. The passage above referencing Houghton from the The London and Country Brewer in the 1750s is looking back to Houghton’s opinion in the last two decades of the 1600s by which time Derby ale is already on the downturn, less than it once was.

We will leave it there for now. This one has hit about 2650 itself. So more in another post soon. Derby ale was something that was worth getting out of the hinterland into the capital. It was made with coke and, before that, straw. Straw was still being used side by side with coke after the new technology was initially introduced. And, whatever it was, Derby ale was already on the way down at the end of the 1600s.

*Which I think is now part of the A6.

**I know “-by” is town so I presume “-went” is river and both relate to “the Der” – whatever that is.

***Another ambassador to Constantinople like Sir John Finch who loved Northdown.

In an

In an  Like you, I am tired. End of year tired. I was tired on Christmas Eve and Christmas Day offers no rest. It feels like the end of a university term and tomorrow we travel. 2019 was a good and busy year – and next week, in my fifty-seventh year, I enter my seventh decade on the planet. I need a rest. So I will be brief this week if only to see if I can get in another nap.

Like you, I am tired. End of year tired. I was tired on Christmas Eve and Christmas Day offers no rest. It feels like the end of a university term and tomorrow we travel. 2019 was a good and busy year – and next week, in my fifty-seventh year, I enter my seventh decade on the planet. I need a rest. So I will be brief this week if only to see if I can get in another nap.