I do not write for the reader. The entire thing, my entire hobby is an exercise in testing my own assumptions. I am trying to solve a very large puzzle. And then I apply the things I come up with – structures of argument in some cases but in other just very big thinking – back into my work life as well as my relationship with life generally. I appreciate that this is all sounding odd – a bit hypomanic – but it is very hard to explain. Last year I even wondered what it would be like to be a beer writer who never drinks beer at all. So it is not so much about being in or out of the bubble but seeing it as a bubble within bubbles next to bubbles and trying to get it all ordered.

I see bubbles. I guess. The other night I woke up at 4 am after a pre-post-apocalyptic dream* and, mulling bubbles for a while afterwards to change the story in my head, thought about what I had been seeing with all this research over the last year, the diving back and forth over centuries. What has struck me even more than ever is how pervasive beer is in our English-speaking culture’s history. There is an obvious reason for that. Alcohol arises naturally, spontaneously. I remember in high school watching out my front window at starlings gorging on the rowan berries in the front yard bush. They were getting quite drunk off the fermented juice. Having a hard time landing or staying on a branch. One bird holding tight to the telephone wire side by side with his or her fellow lost toe grip and swung right round 360 degrees. The berries were loaded with rough country wine. And so became the birds.

This is good. It is a thing of nature. Beer is too. When we say “I would like to shake the hand of the man who invented beer” we tell a fib. Someone somewhere some long time ago came across a puddle. It had formed twice. Once briefly to get the ripe grain laying on the ground damp enough to sprout. And then again later for the now-altered malt to ferment. Someone drank from the puddle and figured out what had happened. All the brewing in all the history of humanity is a repeated effort to replicate the moment. To recreate what that puddle spawned. I see three core tendencies or aspects of those efforts, those replications: vernacular beer, scientific beer, mass market beer. Each is normal… whatever normal is. Better to say they reliably reoccur. Each tendency generates pleasure and profit reliably, too. And breweries – and brewing cultures – over time reflect more than one tendency or aspect. Just the few city blocks of Golden Lane in London, England display all three facets over the centuries. And each tendency generates associated sorts of beer. In a fairly regular pattern.

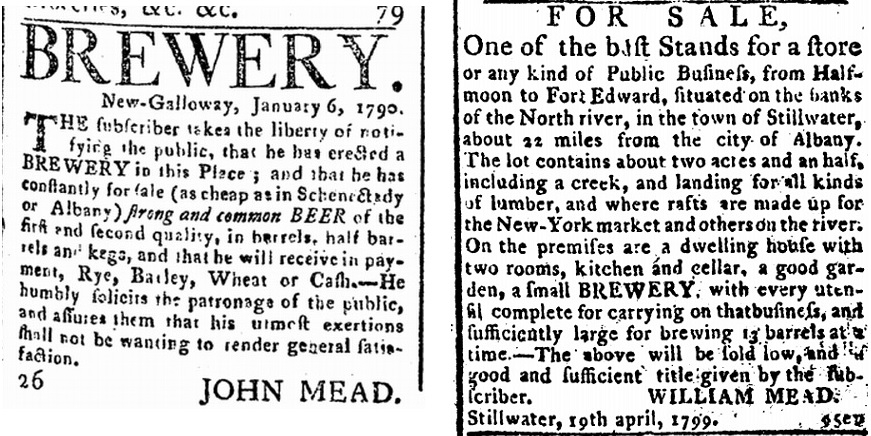

I prefer the idea of vernacular brewing over words like traditional or indigenous. Brewing can speak of a place. Stan will be pleased. Look at that video up there. It’s was shared by** the ever excellent Lars Garshol of Larsblog. Look at what is going on there. It’s likely very similar to how ale was brewed by an early micro. Or by William Mead in 1790s Stillwater, NY. Or at Hoegaarden in the 1400s for that matter. Vernacular brewing depends on a measure of geographical, jurisdictional or economic isolation. Look at the thumbnail. That is a page of Lord Selkirk’s diary from 1803 in which he describes a 12 barrel brewery on the frontier in NNY. Barley is little grown. So the beer is made of a blend of wheat, what barley that can be found and chopped straw. Tidy and efficient. Local resources making local beer for the local population. Unger indicates that how the semi-autonomous jurisdiction of Hoegaarden exported its singular sort of beer throughout the Low Countries of the Renaissance. Understanding local can be very important. Many years ago my part-time farmer father-in-law’s veterinarian traveled to the Ukraine as part of a Canada-USSR project to assist in improving farming practices. He entered a barn where he found the cattle eating fresh cut corn – the whole plant, unripened corn and all. The advice he gave? Kill half the cows. Not enough food to feed all of them from the crops they had on hand. Gotta know what’s possible. Locally.

Scientific brewing represents a refusal. A refusal to accept what vernacular brewing teaches us. It is geared for efficiency or as E.P. Taylor might put it as in the 1942 letter beneath that thumbnail, the avoidance of waste. Coppinger in 1815 wrote of the need for cleanliness and an “economical mode” of building a brewery if the new American Republic was to meet the standards of old world brewing. Efficiency is not code for skill. Coppinger knew it was possible to make “clean bright malt” in a rustic setting. Unlike what some will tell you, pale ale spared from smoke was well known long before the scientific revolution. In addition to the race for efficiency, brewing changes to react to scarcity. Coke was introduced to malting as a replacement for charcoal long before that, as well. It was not so much because it was better as it was due to fact that England’s forests had been drastically thinned out by the late 1500s. The new fuel provided a new way to continue on with brewing. It is related to better husbandy. The late Georgian and early Victorian reports of the recently invented Agricultural Societies on both sides of the Atlantic described the advances in brewing from an economic point of view. Beer is persistent.

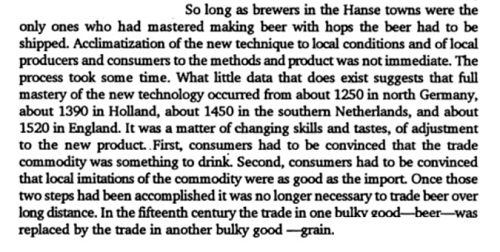

The scale of the mass market has also been an abiding theme with brewing. Taylor of Albany had a pontoon room in the mid-1800s which echoes the royal breweries of ancient Egypt. The Hanseatic trade routes of the 14th and 15th century that allow Hamburg to have a massive brewing industry mirror how the coming of the railway to southwestern Ontario unleashed the carbohydrate laden grain fields out to the British Empire though the previously local brands Labatt and Carling. It took the improvement of the River Trent in 1712 to get the sulfurous local brewer out into the wider world. The English hops trade was subject to scale in the mid-1700s with one merchant London-based James Hunter being “one of the one of the most considerable dealers in hops in England” controlling a huge portion of the marketplace. Beer has a habit to expanding and adapting to meet the possibilities.

If that is so, if brewing has a number of constant attributes like vernacular expression, scientific efficiencies and the opportunism of scale – not to mention the relative certainty of wealth creation – how extraordinary is any era? Is this era? In a way its consistency over time could one of its weirdest characteristics. But then couldn’t the same be said of other persistent commonplace things like shoes, cheese or rope? Something about the pattern make me wonder if it is all a symbiotic relationship held with yeast. Maybe even a wildly successful outcome of an experiment undertaken millennia ago by the Central Yeast Planning Council. It would at least make sense of the formula beer > drinking culture > brewery. Or at least that’s what I think.

*Lots of daytime grey clouds to the horizon views with commentary like “oh, this doesn’t look good.” At one point from an apartment I saw a darker swirling column of grey far off, another moment I was on a path among dunes watching meteor-like flashes in all directions overhead. I never have dreams like this. More Torchwood than Doctor Who.

**Lars commented that he was not the source of the video. I think I saw him link to it now that I think of it.

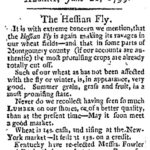

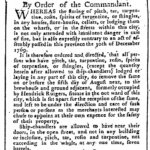

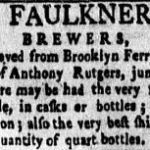

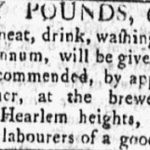

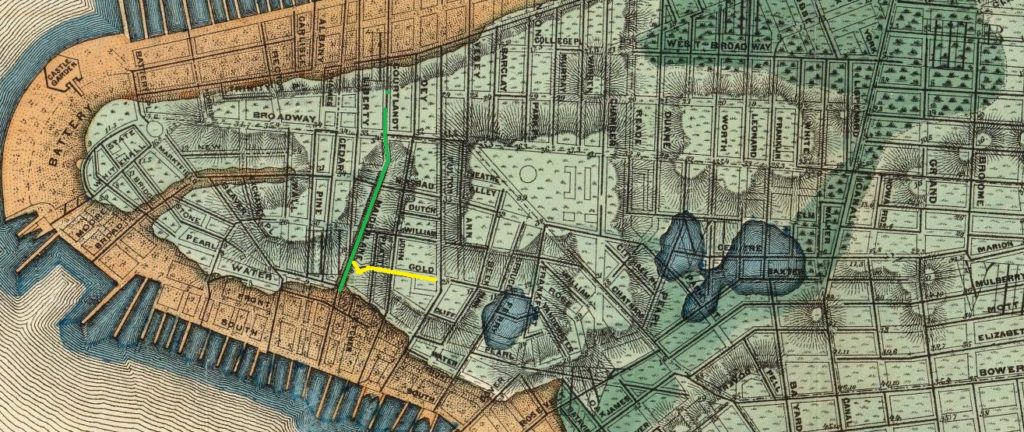

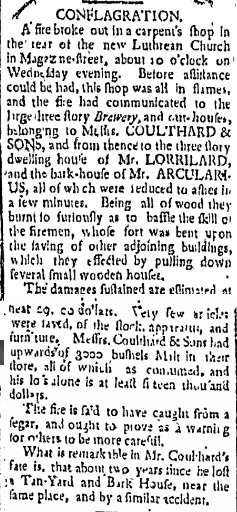

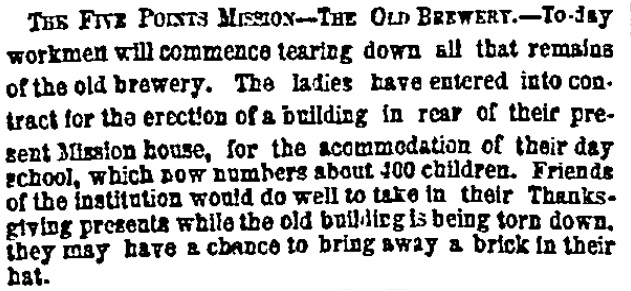

Anyway, the new brewery burned, too. I think they all burned, these old breweries. In the 1 July 1797 edition of Greenleaf’s New York Journal, right, it was reported that all the malt was lost and the whole business was a write off. An errant cigar at the nearby site of the new Lutheran Church apparently started it. He gets up and operating again as by July in 1806, his beers are being

Anyway, the new brewery burned, too. I think they all burned, these old breweries. In the 1 July 1797 edition of Greenleaf’s New York Journal, right, it was reported that all the malt was lost and the whole business was a write off. An errant cigar at the nearby site of the new Lutheran Church apparently started it. He gets up and operating again as by July in 1806, his beers are being

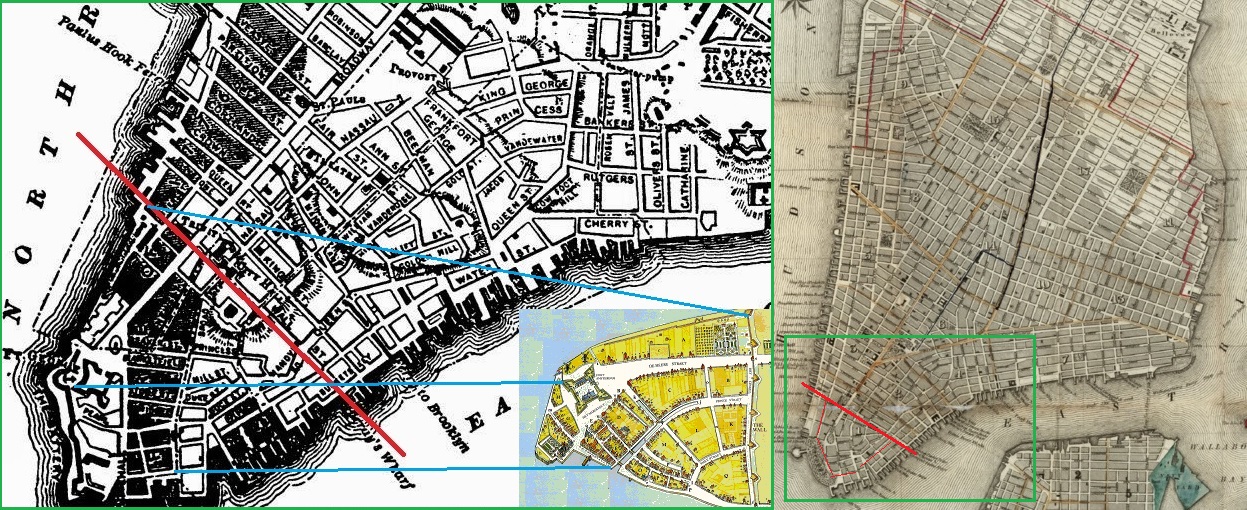

Middagh Street is

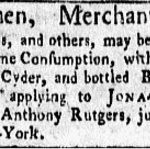

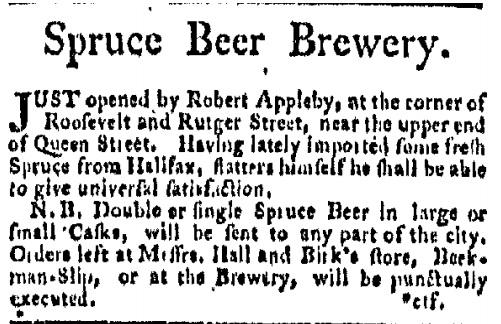

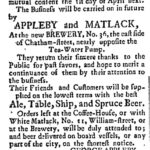

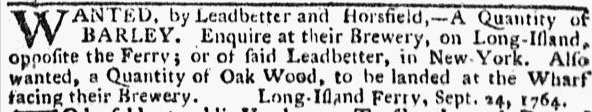

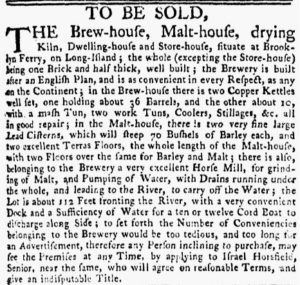

Middagh Street is  To the left you see something of the motherlode. The golden moment you dream of finding. It is the notice of the apparently unsuccessful sale of the brewery placed in the New York Mercury of

To the left you see something of the motherlode. The golden moment you dream of finding. It is the notice of the apparently unsuccessful sale of the brewery placed in the New York Mercury of