It gets like that in January. Counting the days to the warmer ones like prayers upon beads passed through the fingers. It’s time. Please be March soon. Please. Warmth. Now! Come on!! Time, like grace, arrives in its own pace I suppose. Even calling this a Thursday post is jumping the gun a bit. These things get plunked together mostly on Wednesday. These things matter. Anyway, what’s been going on in the news?

I lived in PEI from 1997 to 2003 and am pretty sure John Bil shucked my first raw oyster. Love struck I was. Carr’s was an eight minute drive from my house and I often bought a dozen or two there to take out to the back yard and suck back on a Saturday afternoon. RIP.

Our pal Ethan and Community Beer Works are working with the owners of Buffalo’s Iroquois brand to revive a version of the venerable brew. An interesting form of partnership where craft leans of community pride in legacy lager.

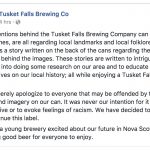

Carla Jean Lauter tweeted the news Wednesday afternoon that Nova Scotia’s newbie Tusket Falls Brewing had decided to withdraw its Hanging Tree branding for one of its beers. Rightly so and quickly done as far as I can tell. That’s the Facebook announcement to the right. This was a good decision on their part but not one that goes without consideration. I grew up in Nova Scotia and, among other lessons learned in that complex culture, had the good fortune to be assigned as law school tutor in my last year to one of the leaders of the Province’s version of the Black Panther movement when he was in first year, the sadly departed, wonderful Burnley “Rocky” Jones. He did all the teaching in that friendship. I would have loved to have heard his views on the matter. See, Loyalist Canada was settled in the 1780s by the British Crown as a refuge for the outcasts, including African American freed former enslaved Loyalists, seeking shelter after the dislocation of the American Revolution. Court justice there as it was here in Kingston included hanging as part of that. Hell, in the War of 1812 at Niagara there was still drawing and quartering. As I tweeted to Ms Pate, another Bluenoser, the hanging tree could well symbolize peace, order and justice in Tusket as much as bigoted injustice elsewhere. Or it could represent both… right there. Were there lynchings in southwestern Nova Scotia? Some stories are more openly spoken of than others. Slavery lingered on a surprisingly long time here in Ontario the good. We talk little about that. And Rocky and others do not fight that good fight without good reason. We might wish it should and could depend on what happened in that place. But somethings are no longer about the story of a particular place. Somethings about beer are no longer local. And its not “just beer” in many cases. Yet, we happily talk of war. Q: could a Halifax brewery brand a beer based on the story of Deadman’s Island?

Carla Jean Lauter tweeted the news Wednesday afternoon that Nova Scotia’s newbie Tusket Falls Brewing had decided to withdraw its Hanging Tree branding for one of its beers. Rightly so and quickly done as far as I can tell. That’s the Facebook announcement to the right. This was a good decision on their part but not one that goes without consideration. I grew up in Nova Scotia and, among other lessons learned in that complex culture, had the good fortune to be assigned as law school tutor in my last year to one of the leaders of the Province’s version of the Black Panther movement when he was in first year, the sadly departed, wonderful Burnley “Rocky” Jones. He did all the teaching in that friendship. I would have loved to have heard his views on the matter. See, Loyalist Canada was settled in the 1780s by the British Crown as a refuge for the outcasts, including African American freed former enslaved Loyalists, seeking shelter after the dislocation of the American Revolution. Court justice there as it was here in Kingston included hanging as part of that. Hell, in the War of 1812 at Niagara there was still drawing and quartering. As I tweeted to Ms Pate, another Bluenoser, the hanging tree could well symbolize peace, order and justice in Tusket as much as bigoted injustice elsewhere. Or it could represent both… right there. Were there lynchings in southwestern Nova Scotia? Some stories are more openly spoken of than others. Slavery lingered on a surprisingly long time here in Ontario the good. We talk little about that. And Rocky and others do not fight that good fight without good reason. We might wish it should and could depend on what happened in that place. But somethings are no longer about the story of a particular place. Somethings about beer are no longer local. And its not “just beer” in many cases. Yet, we happily talk of war. Q: could a Halifax brewery brand a beer based on the story of Deadman’s Island?

My co-author Jordan has made the big time, being cited as “Toronto beer writer and expert” by our state news broadcaster.* With good reason, too, as he has cleverly taken apart the fear mongering generated around the reasonable taxation of beer.

This is really what it is all about, isn’t it? Well done, Jeff. The setting, style and remodeling of his third pub, the

This is really what it is all about, isn’t it? Well done, Jeff. The setting, style and remodeling of his third pub, the

The Ypres Castle Inn all look fabulous. Good wee dug, tae.

I don’t often link to a comment at a blog but this one from the mysterious “qq” on the state of research into yeast is simply fantastic: “[t]o be honest anything is out of date that was written about the biology of the organisms making lager more than three years ago…” Wow! I mean I get it and I comments on the same about much of beer history, too, but that is quite a statement about the speed of increase in understanding beer basics. Read the whole thing as well as Boak and Bailey’s highly useful recommended lager reading.

Max finally gets a real job.

Gary Gillman has been very busy with posts and has written one about a very unstylish form of Canadian wine, native grape Canadian fortified wine, often labeled as sherry. Grim stuff but excellently explained. As I tweeted:

Well put. These were the bottles found, when I was a kid, empty up an alley or by forest swimming holes. I thought we had a few examples of better fortified wine ten or so years ago. But, likely as the PEC and Nia good stuff sells so well, no attraction to a maker.

Gary gets double billing this week as he also found and discussed the contents of a copy of the program from the first Great American Beer Festival from 1982. I have actually been pestering Stan for one of these off and on for years only to be told (repeatedly) that archiving was not part of the micro era. Tell me about it, says the amateur boy historian. The 1982 awards are still not even listed on the website but that seems to be the last year of the home brew focus. Anyway, Gary speaks about the hops mainly in his post. I am more interested in the contemporary culture: which presenter got what level of billing, what the breweries said of their beers. Plenty to discuss.

More on closings. Crisis what crisis? In the room the women come and go / Talking of Michelangelo. What’s it all about, Alfie?

That’s enough for this week. Plenty to chew on. See you in February!

*All I ever got was “an Ontario lawyer who reviews beers on his blog…” like I am some sort of loser…