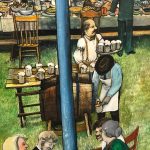

Well, it sure is getting quiet out there. I put off gathering together my thoughts until Wednesday night and, still, it felt like I’d only posted the last weekly update the day before. Christmas is a-comin’. Right off, however, I need to show you the photo of the week. To the right, tweeted out by Joe of @whatjoewrote after he wrote “making a sacred pilgrimage to a golden place today.” I love a lot about the image but probably the best is that Orval font.

Well, it sure is getting quiet out there. I put off gathering together my thoughts until Wednesday night and, still, it felt like I’d only posted the last weekly update the day before. Christmas is a-comin’. Right off, however, I need to show you the photo of the week. To the right, tweeted out by Joe of @whatjoewrote after he wrote “making a sacred pilgrimage to a golden place today.” I love a lot about the image but probably the best is that Orval font.

Next up, Stan is finally back. Free loader Stan. Stan the travelin’ man. Stan the guy who drifts into work at 10:45 am saying wide-eyed “what? whataaa?!?” to the questioning stares. His final roundup for The Session begs the question of why we don’t have one mega-blog and pay him to edit. Why?

Quere: if two contract brewers merge in the forest, does anybody hear?

Nothing says Yuletide like bankruptcy law news. Turns out DME, the eastern Canadian brewing equipment manufacturer, is now confirmed to be $27 million in debt of which $18 million is owed to the Royal Bank of Canada:

The entire list names more than 700 creditors between DME’s operations in Charlottetown and Abbotsford, B.C. The creditors list includes companies from around the world, along with individuals and government agencies. More than 50 of the companies owed money are on P.E.I., along with approximately 140 people with Island addresses… Around $1 million of that is listed as being owed to P.E.I. companies. However, nearly half of the companies and individuals named in the creditors document don’t have dollar amounts listed. Those numbers still have to be determined. The final amount DME owes could change.

So far, as I mentioned last week, these are old stomping grounds and I know the receiver’s lawyer and the judge, now have fed the press backstage and even recommended counsel to international interests. And I am not even involved. Here is the list of the additional unsecured creditors. Their own lawyers are owed around $435,000. Wow. Note that the Indie Alehouse deposit is there but without a noted value. The Toronto Star reported it as being worth $800,000. Many other breweries with deposits are all there but also without a noted value. Sift the clues. Go ahead.

Responding to the news from two weeks ago that Norm was moving away from beer, Jason Notte has posted a thread of tweets that shares his views on the affect of alcohol on the health of writers, including this one:

A few years ago, the great @Will_Bunch told me something I wasn’t ready to hear: Craft beer isn’t a trend story and beer consumption isn’t just an industry. When you see rising beer consumption and “drunkest states” listicles, there’s some hurt behind those numbers.

It’s true. You might not like it but it is true. Along those lines, perhaps in miniature, Boak and Bailey recorded a brief conversation overheard in a UK pub:

“My plan is to get back to the office after lunch absolutely hammered.”

“Blimey, careful, mate.”

“Nah, it’s fine — it’s December!”

Yikes. Yik even. To make us all feel as we should – distracted – Mark Dredge has posted some fabulous photos from Vietnam. Fabulous.

A bit less fabulously, I don’t particularly have that particular hate on for “listicles” that those never asked to write one have but this one works for me, 25 from Fortune magazine. It expressly contextualizes the selection well and also notes price. Happy to see that the Ontario’s price for #2 is 50% of what is suggested by the list. I will have my fill over the next few weeks. Ha ha! Sucks to sucks if you don’t live here.

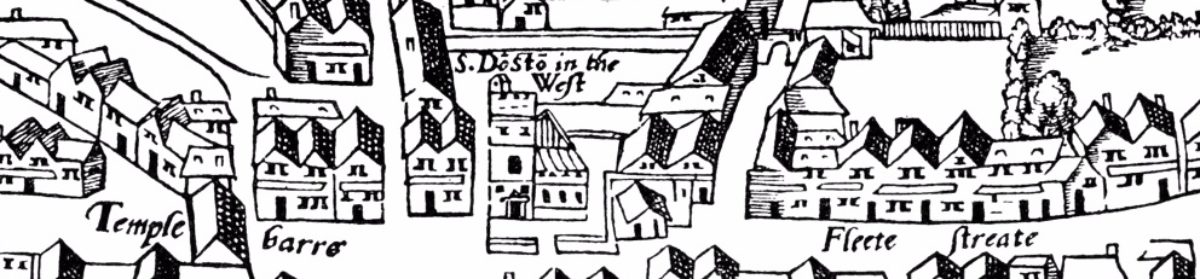

If your brain is like mine, you might like this. Issue #163 of Brewery History has been released from behind its paywall for everyone to enjoy. The article on 15th century brewing in England is of particular interest to me but there are a range of articles to explore.

I came upon this article, no doubt funded by shadowy interests*, that argues that US tariffs on aluminum have led to an increase in reliance on US made beer cans:

President Donald Trump’s aluminum tariff won’t make beer taste better, but it’s succeeded in boosting the economy, according to a report published on Dec. 11 by the Economic Policy Institute. The research argues that tariffs imposed on aluminum and steel have led to increases in U.S. employment, production and investment.

Finally, in his big comeback** Stan did note something I myself should also address:

Boak & Bailey recently explained how they choose what to put in their Saturday lineup. In the interest of transparency, my rules are pretty arbitrary. I include links here to stories I think you should enjoy reading, either because the writing is terrific or the ideas within merit thinking about, or both. I also include links to stories I simply want to comment on.

Me? I don’t really think of you. I think of the news as something that develops and needs tracking. Beer news needs its own aggregation. So I keep graphs. I make tables. I smoke a pack and then smoke another as Wednesday night turns into Thursday morning. I am even thinking about how Putin and Xi have minions and how once one maybe stumbled across my social medial presence. I know I am being watched. Help! No? Look, I realize this is mid-December filler but if you think about it from my perspective, well, maybe it will make a little sense. Just a little?

That being said, there is only one more roundup before Christmas and two before this year is dead. Dead dead dead. Let’s think about that a bit before we get pounded at lunch, shall we? A good time to reflect on things. Things like pasting together a weekly charade of a commentary on the brewing industry. Things like concerning myself more with the roasts to come rather than the giving one ought to give.

Enough from me! B+B on Saturday and Stan next Monday.

*Note: “The EPI advocates for policies favorable for low- to moderate-income families in the United States.“

**What? You want every footnote to mean something?