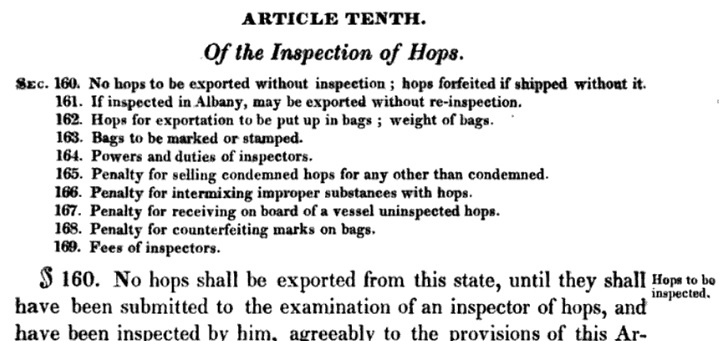

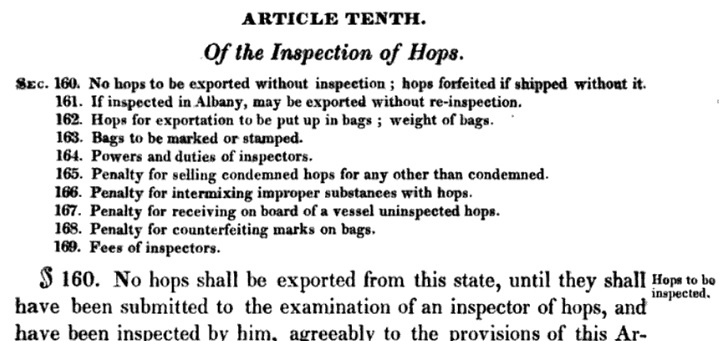

It’s a funny thing, history. Sometimes you can only see a bit. Just the effects of something but not the cause. Or just one rabbit hole to chase down all the while missing the larger field below which it sits. Coming across the Article Ten above in a set of laws entitled The Revised Statutes of the State of New-York: Passed During the Years One Thousand Eight Hundred and Twenty-seven, and One Thousand Eight Hundred and Twenty-eight… immediately struck me that way. It’s a bit of a dislocated. It sits among laws about the inspection of other things: pickled fish (Art.4), sole leather (Art. 9) for but two examples. It seems pretty clear that in 1827 the need for inspecting things was important to New Yorkers. Section 161, however, may have laid an unintended trap in the general scheme:

Hops inspected in the city of Albany, may be exported thence, or be sold in and exported from the city of New-York, without being subject to re-inspection in the city of New-York.

First, note that the laws of the state of New York described the state of New York as coming from “New-York” is in itself a question… I wonder if I can find a highly placed New York law librarian who might address this question. Second, notice that there are two points of export. As you the careful reader might have picked up over the previous six or seven years New York had two centers, one for the Dutch and one for the English, which became one center for the administrative life and one for the financial. A certain tension was being addressed in the law.

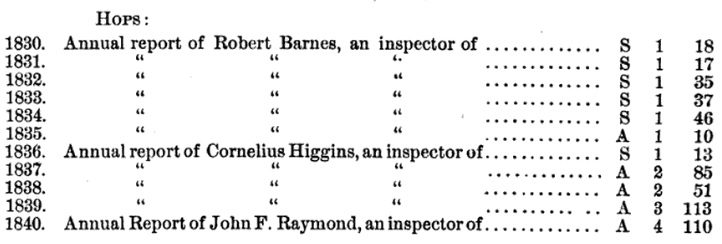

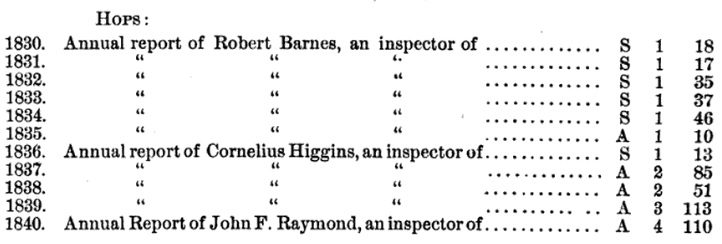

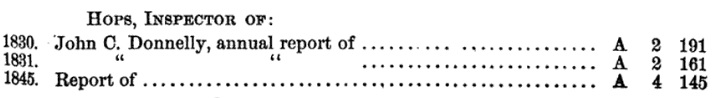

Helpfully, there are other books one can find on line. Such as the General Index to the Documents of the State of New York, from 1777 to 1871, Inclusive published by the New York State Assembly. And in that index there is the following fabulous entry:

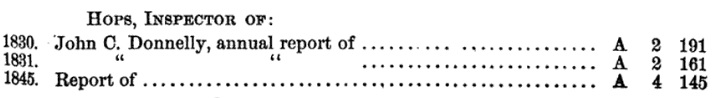

What do we see? Well, it took a bit of time to get the whole hop inspecitng thing going. The law came into being in 1827-28 but the first report only is presented to the government in 1830. Plus there were three inspectors over one decade. But none overlap. Which is a problem. Because there are supposed to be two concurrently operating inspection processes going on. Scanning around I find the answer. In 1871’s General Index at a page 109 pages before the page above has the index entry “HOPS, INSPECTOR OF, see Albany, New York” – note: without a hyphen. And when one goes looking for that you find on page 17:

So, the Albany inspector was John C. Donnelly of whom I immediately presume Craig will have a list of prior offenses the length of my arm. Why would I say such a thing? Did I ever mention we co-wrote a book on the history of brewing in Albany? You will also see, he did not last long. Why might that be? Well, let’s look at what else is out there to have a look at. We actually have the 1830 report out of the New York City office which reads in full:

ANNUAL REPORT

Of Robert Barnes, an Inspector of Hops, for the county of New-York.

To the Honourable the Legislature of the State of New-York.

The hop inspector respectfully sheweth :—In conformity with the state laws on the subject of inspection, I herewith transmit to the Legislature a statement of all the hops inspected by me during the last twelve months, ending 1st mo. 1st, 1831.

Inspector’s Report for the City of New-York, for the year 1830.

606 bales of hops, 127,840 lbs., average price, say, 12 1/2 cts $15,980

Inspector’s fees at 10 cents per 100 lbs.,…. $127 84

Deduct for extra labor, materials, and other

incidental expenses, at 31 cents per bale, 21 21

Inspector’s available funds, (no emoluments) 106 63

From the inadequate means, as stated above, towards supporting a competent judge of the article of hops, I respectfully solicit the legislature to abolish the Albany Inspection, on all hops exported from the state. Shipments when confined to a single brand, would render it more hazardous for those making encroachments on our state laws, which in some degree is followed, and by superior management, rendered difficult of detection.

ROBERT BARNES

New-York, 1st mo. 1st January, 1831.

So, Robert Barnes of New York City… err… County had John C. Donnelly kicked out of a plum appointment at the bottom of his very first report. Is that it? I take it that rendering “it more hazardous for those making encroachments on our state laws” by superior management is an oblique way of suggesting that Mr. Donnelly was in on some bad behaviour. It wasn’t a one sided discussion. The Donnelly report was received by the State Assembly on Friday February 4, 1831.

A month later, as a final matter of its working day on Friday March 4, 1831 the New York House of Assembly voted as follows:

Resolved, That the annual reports of Robert Barnes, inspector of hops in the city of New-York, and John C. Donnelly, inspector of hops in the city of Albany, be referred to the committee on trade and manufactures; and that said committee report to this House, what alterations (if any) are necessary in the law regulating the inspection of hops in this State.

It appears that the victory by Barnes might not have been entirely the sort of self-serving move one might expect from appointees of the era. In his 1835 report to the government he set the following out as part of his request to continue in the position:

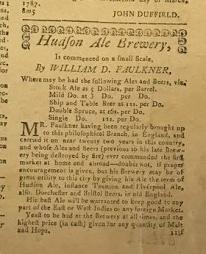

My having been a brewer upwards of thirty years in this city, and since, seven more as inspector, a sufficient time to complete a thorough knowledge of its necessary duties, and respectfully solicits a continuance in office, which would confer a lasting obligation on your friend.

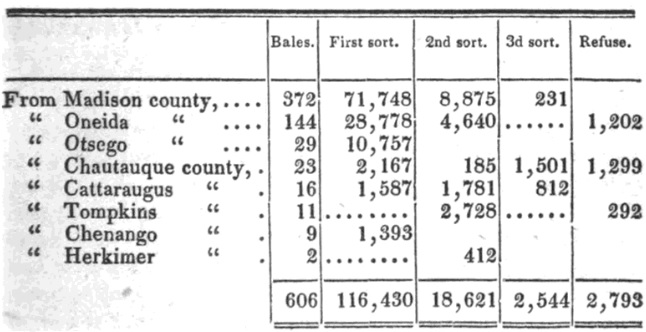

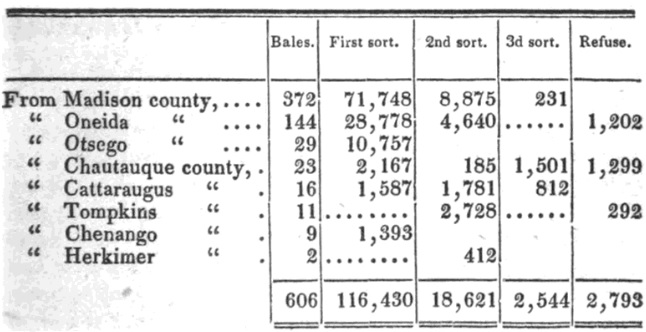

It is not like Barnes was not connected to the industry. Craig actually mentioned him in a post back in 2012. Here’s a notice of his from the New York Commercial Advertiser of 1807. His role as inspector appears to be a part time gig. Note also that during those years from the 1830 crop to that of 1834 (each reported the next year) there was an increase in value from $15,980 to $129,656. The volume of hops exported as well: 606 bales of exported hops in 1830 became 4,235 bales reported in the 1835 report. So why were the inspectors unhappy? Why did one report shutting down the other’s office? We actually have John C. Donnelly’s report from Albany submitted in February 1831 which has this fabulous table:

Turns out all of the 606 bales of hops reported in Barnes’s 1831 report were entirely sourced in upstate New York to the west and directly upstream… err, up the Erie Canal from Albany. So, as a first thing, if all the hops are passing both cities why have two inspection points? As a second? Not sure. I can’t find reference to hop inspections referenced in either the Journal of the NY State Assembly for 1832 or in the Documents recorded as being filed with the Assembly in that year. I may update if I find more information on the run in between Messers. Barnes and Donnelly but for now let this be a lesson to you all. Even a decent set of records should be considered partial and, therefore, imperfect. Ah, the human condition made manifest, as it usually is, in the inspection reports of primary agricultural production.

What is a place like that even called? A tap room? No, a tap room is the sorta thing you find in a back room at a place like the Laxfield Low House. This is just a tap. And, the weird thing, is that its is only that – a tap. One. Click on the photo. So you are getting the last guys beer left overs in the space between the one spigot works its way back into the stand. That might be an ounce. Fine if its all macro gak but, like one of those soda guns behind a bar, everything is getting served through the same nozzle. A bit of stout in your wit? One nozzle. Which no one wipes down between fill-ups. Which means it’s like an elementary school water fountain that spews beer. And whatever else is on that nozzle.

What is a place like that even called? A tap room? No, a tap room is the sorta thing you find in a back room at a place like the Laxfield Low House. This is just a tap. And, the weird thing, is that its is only that – a tap. One. Click on the photo. So you are getting the last guys beer left overs in the space between the one spigot works its way back into the stand. That might be an ounce. Fine if its all macro gak but, like one of those soda guns behind a bar, everything is getting served through the same nozzle. A bit of stout in your wit? One nozzle. Which no one wipes down between fill-ups. Which means it’s like an elementary school water fountain that spews beer. And whatever else is on that nozzle.