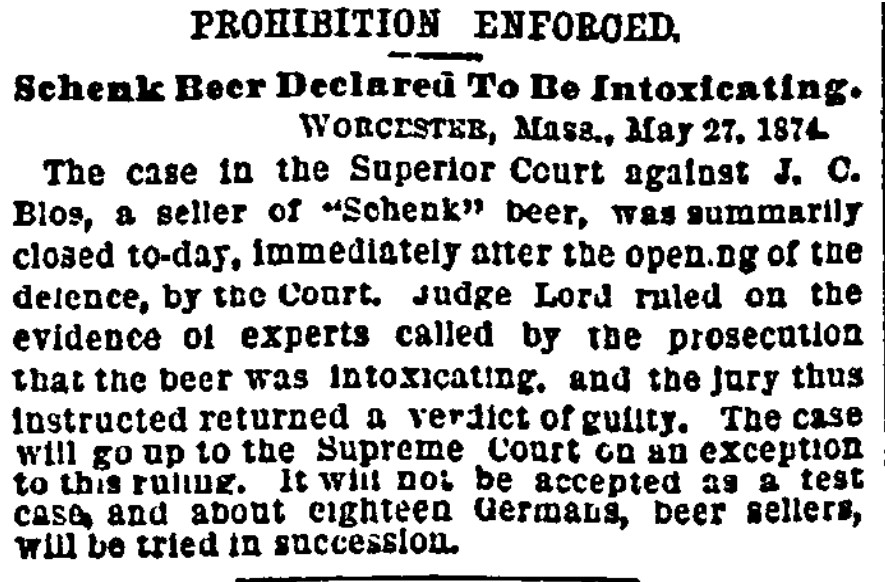

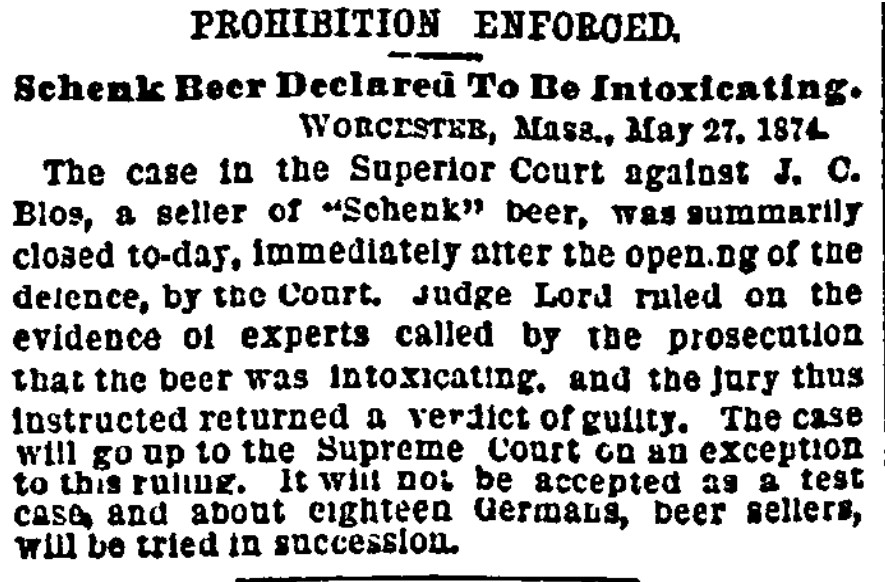

That’s from the New York Herald of 28 May 1874. Schenk is one of those words that flits around the edges of US beer history popping up in scientific tables, included in passing references before, say, 1900 that is one of the more irritating to research. One simple reason is that it was / is a reasonably common surname. And it may suffer from that problem of speculation in the guise of conclusion we see too much of. Footnotes and primary records are the regular cure for that ailment so let’s see what we can find out before we form the image in our mind’s eye.

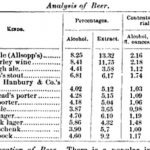

First, let’s start relatively near the end. In every child’s favourite bedtime book, Johnson’s New Universal Cyclopaedia: a Scientific and Popular Treasury of Useful Knowledge, Volume 1, at page 442 we read this in the sub-article on “Lager Beer”:

Three varieties of this beer are made: (1) “Lager” or summer beer, for which 3 bushels of malt and IA to 3 pounds of hops are used per barrel, and which is not ready for use in less than from four to six months. (2) “Schenk” winter or present-use beer: 2 to 3 bushels malt and 1 pound hops per barrel; ready in four to six weeks. (3) Bock bier, which is an extra strong beer, made in small quantity and served to customers in the spring, during the interval between the giving out of the schenk beer and the tapping of the lager. In its manufacture 3 1/2 bushels of malt and 1 pound of hops per barrel are used, and it requires two months for its preparation.

The encyclopedia was produced by the A.J. Johnson publishing house of New York City run by one Alvin J. Johnson. You can click on the image to the right where each of the three sorts of beer are prefaced by the word “Munich” – which is interesting. What I also like about that passage is how well it aligns with one other reference from a completely difference source. In 2011, the terribly reliable Ron wrote a post about Vienna malt and quoted a long passage from the British Medical Journal 1869, vol. 1 and particularly from pages 83 to 84:

The encyclopedia was produced by the A.J. Johnson publishing house of New York City run by one Alvin J. Johnson. You can click on the image to the right where each of the three sorts of beer are prefaced by the word “Munich” – which is interesting. What I also like about that passage is how well it aligns with one other reference from a completely difference source. In 2011, the terribly reliable Ron wrote a post about Vienna malt and quoted a long passage from the British Medical Journal 1869, vol. 1 and particularly from pages 83 to 84:

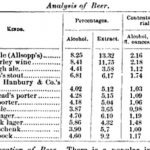

Generally speaking, the beer drunk in Austria and Germany has less alcoholic strength than that consumed here. The strongest Kinds, such as those known in Bavaria by the names “Holy Father”, “Salvator”, and “Buck”, rarely contain so much as 5 per cent, by weight of absolute alcohol. The store-beer, or lager bier, generally contains about 3.5 per cent., ranging from 4 to 2.8 per cent. ; and the ordinary beer for quick draught, schenk bier, corresponding in that respect to our porter, contains from 2.25 to 3.5 per cent, of alcohol. In the Austrian dominions, the beer is generally preferred rather weaker than in Bavaria ; but in Austria, the organisation of the breweries, and the system of conducting the business, have been developed in such a manner as to assimilate more to the vast establishments we have in this country.

Now, to my mind that looks like two sources from two English-speaking countries within nine years of each other each presenting as fairly authoritative information about a classification of beer from a third culture.* For present purposes, this is useful enough to rely upon as a first principle that, whatever it was, in the latter third of the 1800s, schenk was understood as and also the common word for German beer of a weaker sort than middling lager and stronger bock. It is considered to exist on a continuum and not of a difference class than lager or bock. It is an adjective as much as a noun. A degree of strength.

This is interesting. Boak and Bailey’s bibliographical guide to entering an enhanced understanding of lager included a 2011 article by Lisa Grimm – “Beer History: German-American Brewers Before Prohibition” – which states this about the entry of lager into the brewing culture of the United States:

Many historians attribute the first lager beer brewed in America to John Wagner, a Bavarian immigrant who set up shop in Philadelphia in 1840, though some of that notice is probably due to the chain of events he helped kick off—Maureen Ogle points out in her excellent Ambitious Brew that two German immigrants were brewing lager on a small scale in 1838 in Virginia.

This passage follows the statement “German brewers were a relatively late addition to the scene, arriving in large numbers only in the mid-19th century.” This timing aligns with the post I wrote about a rather alarming New York City Sunday afternoon attack on a public house** which I entitled “An Anti-German Anti-Lager* NYC Riot In 1840” with that asterisk. See, I assumed Germans and lager were common entrants into the NYC scene but as Gary, well, chided me (let’s be frank) in relation to… 1840 slightly predates the date lager is understood to have arrived in New York with George Gillig… or rather the date Gillig takes on brewing lager. It appears he brewed something else from 1840 to 1846.

Additionally, that bit brings up national pride right about now. Jordan, in part of our book Ontario Beer, wrote that the first brewer on record in Waterloo Township was George Rebscher who opened his establishment in 1837:

It should come as no surprise that Rebscher, as a German brewer from Hesse in Franconia, brought with him the brewing techniques that were used in his homeland. Rebscher was the first brewer of lager beer in North America. What we cannot know is exactly what the lager might have been like. It seems likely the unfiltered styles that were popular in Franconia might have represented some of the early output. Given what we know of brewing in the early stages of a settlement in Upper Canada, it is relatively unlikely that George Rebscher’s lager would have been made entirely of barley for the first year or two of production.

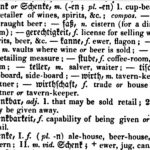

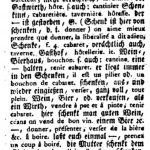

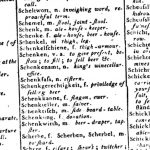

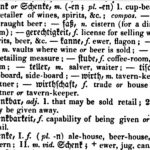

Which is all very interesting. In the 1843 edition of Flügel’s Complete Dictionary of the German and English Languages there is a translation given at page 508 for “schenk” and a number of related words. You can read it if you click on the thumbnail to the right. And if you can struggle with the Gothic script you will see that it is related to ideas of draught and tavern. Sort of table beer, perhaps. By contrast, lager-bier is defined at page 353 as “beer for keeping, strong beer.” Jordan went on to suggest that the early beer from Rebscher was more zwickelbier than kellerbier based on the lack of aging. To my mind, based on the above, that sounds a lot like a beer that is more schenk than lager, too.

And… that’s it. Frankly whether it was Rebscher, Wagner or Gillig really does not matter for today’s purposes. These gents are all examples of the folk included in the wave of German-speaking immigrant to the western hemisphere in Q2 1800s. It’s The Beginning. The beginning of lager. Well, a beginning of what is called lager. The beginning of German beer in North America. New beer for a new wave of immigrants in the 1830s and 1840’s. Sorta. Sorta maybe. The problem with the story is that there are two key elements that exist in North America well before this genesis story: German beer and… Germans. See, the Germans who came to North America in the second quarter of the 1800s were not the first. The Historical Society of Pennsylvania has summarized it this way:

The largest wave of German immigration to Pennsylvania occurred

during the years 1749-1754 but tapered off during the French and Indian Wars and after the American Revolution… By the time of the Revolutionary War, there were approximately 65,000 to 75,000 ethnically German residents in Pennsylvania. Some historians estimate the number as high as 100,000. Benjamin Franklin wrote that at least one-third of Pennsylvania’s white population was German.

Which is interesting. There was German beer of some sort and there were Germans not only well before lager shows up in America but plenty of Germans were before the American Revolution. But they were not necessarily the same sort of Germans. As that piece states, the German immigrants of the 1830s and 1840s came from northern and eastern Germany and were Catholic whereas the earlier Pennsylvania Germans tended to come from the southern German principalities and were Lutherans or other sorts of Protestants. Which may well mean, then as now, the beer was different.

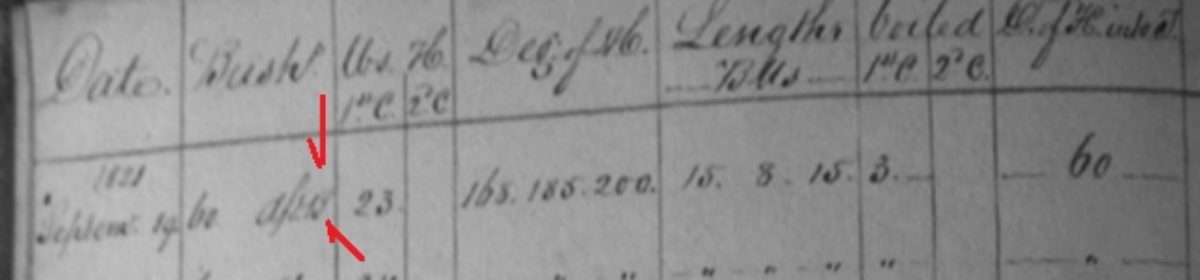

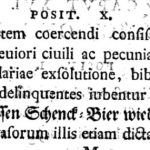

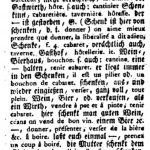

So, armed with that, let’s go further back. If we do, we see that “schenk” was a term with a prior history. As illustrated to above the far left, Heinrich Hildebrand used the term in his early 1700s philosophical treatise Jurisdictio Universa Secundum Mores Hodiernos Compendiose Considerata. You can see it there in Gothic German script as an illustration of his tenth hypothesis set out in Latin. And, no, I have no idea what he’s talking about either. “Schenk” also shows up, as up there in the middle, in this entry in a French language dictionary of German terms from 1788, the Neues Teutsches und Französisches Wörterbuch. And, to the upper right, here it is in an English-German dictionary from Britain published in 1800. So, schenk was a thing before lager came to the USA. At this point, not so much the adjective explaining relative strength. Note also how broad the various associated forms of the word are. In 1800, a tavern keeper is a schenk or a schenke depending on gender. It has a meaning more its own than by the end of the 1800s.

Let’s go a bit lateral now. Bear with me. We saw a year and a half ago that in the 1820s there was something called cream beer being sold in New York which was associated with the Germans of Pennsylvania. A sort of fresh beer… draught… table beer perhaps. There is another term used around the same time – “Bavarian” – sometimes with “ale” and sometimes with “beer.” The New York Evening Post of 20 January 1836 uses the term “Bavarian beer” in a long article, “The German Prince In Germany And France” where it is said the German author Jean Paul was fond of it.

Let’s go a bit lateral now. Bear with me. We saw a year and a half ago that in the 1820s there was something called cream beer being sold in New York which was associated with the Germans of Pennsylvania. A sort of fresh beer… draught… table beer perhaps. There is another term used around the same time – “Bavarian” – sometimes with “ale” and sometimes with “beer.” The New York Evening Post of 20 January 1836 uses the term “Bavarian beer” in a long article, “The German Prince In Germany And France” where it is said the German author Jean Paul was fond of it.

And then there is swankey which , as noted by Boak and Bailey in the June 2015 edition of BeerAdvocate, was a name of a beer in Pennsylvania which was a lot like a name for a light rustic beer in Cornwall England, swanky. The word swankey with an “e” was used in a 12 May 1849 article on a crisis at sea in the New York’s Weekly Herald. It was used in rather unflattering terms as you can see to the right: vinegar, brandy, saltwater and molasses. Notice that the ship left from Delaware. Next to eastern Pennsylvania. A lowbrow making a lowbrow reference to probably a lowbrow drink.

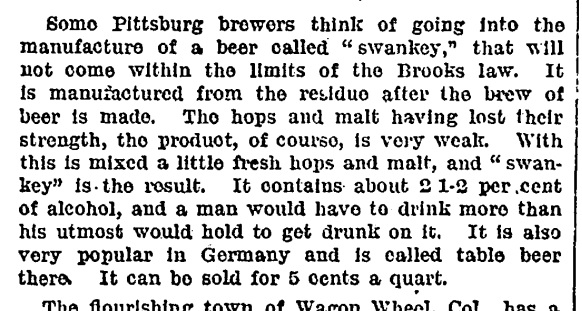

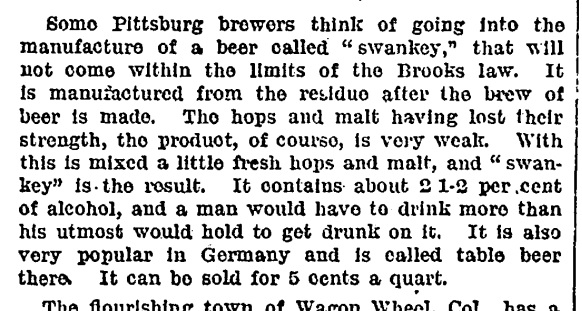

Hmm… then we see that the 28 April 1888 edition of the New York Tribune included a passage in a newsy notes column on a enterprise dedicated to the brewing of swankey which I set out in full below:

Brook’s law was an 1880’s temperance law in Pennsylvania. And low strength table beer “is very popular in Germany.” Stan notes a similar add from Wichita from around the same year in his book Brewing Local but suggests swankey started there. Hmm – the police blotter article up top from twelve years before would discount an 1888 start if there is a connection. I wonder if it actually is something of the end point for the concept. See, swank is an old word, too – like schenk.*** In the common sense has a rather interesting etymology. Full of notions of youth and swagger and stagger before it was a fifty cent word for trendy.

And if we are honest, swanky and schenk can start to sound a bit alike if you mix in various accents especially if the schenk is schenke. Mixed accents of mixing peoples. See, there is a Cornwall and Pennsylvania connection, too. Quakers moved from Cornwall to western New Jersey and eastern Pennsylvania in the later 1600s. Pennsylvania has a few nicknames and one is the Quaker State, immortalized by the engine oil as well as a brand of oatmeal. Did they bring the word swanky in the 1600s, meet up with Germans in the 1700s making schenk, merge them in to swankey and maybe brand it as cream beer in the early 1800s to explain it to people who didn’t get the local lingo. That 1880s reference Stan notes might be more of an echo, a remembrance of beer words past.

Seems a bit of a convenient stretch, doesn’t it. But we are talking about a pretty small and culturally discrete population. There are only 240,000 people in Pennsylvania in 1770. And we see three low alcohol not-lager beers coming out of the same community over time and at a time when there was no real finesse about neatly splitting hairs over whether a beer is of one sort or another. Think about it. Maybe a stretch. Maybe not.

*Note also this definition from the 1885 edition (and not the claimed 1835 edition) of The Progressive Dictionary of the English Language: A Supplementary Wordbook to All Leading Dictionaries of the United States and Great Britain published by the Progressive Publishing Company of Chicago: “Schenk-beer (shengk ber), n. [G. schenk-bier, from schenken, to pour out, because put on draught soon after it is made.] A kind of mild German beer; German draught or pot beer, designed for Immediate use, as distinguished from lager or store beer. Called also Shank-beer.“

**The term “German public house” was a thing in New York before 1846. The Spectator newspaper used the term on 2 April 1842 to describe one of the buildings lost in a great fire.

***This looks like a reference to “schenkebier” from the 1400s.